Async Runtimes Part II

Here’s a link to the code on GitHub

This post is a follow up to a previous post, where I built a basic custom Future and hooked that up to an Executor and polled the future to completion.

This time I’m going to build a single-threaded event loop that uses async I/O interfaces in ~500 lines of Rust code.

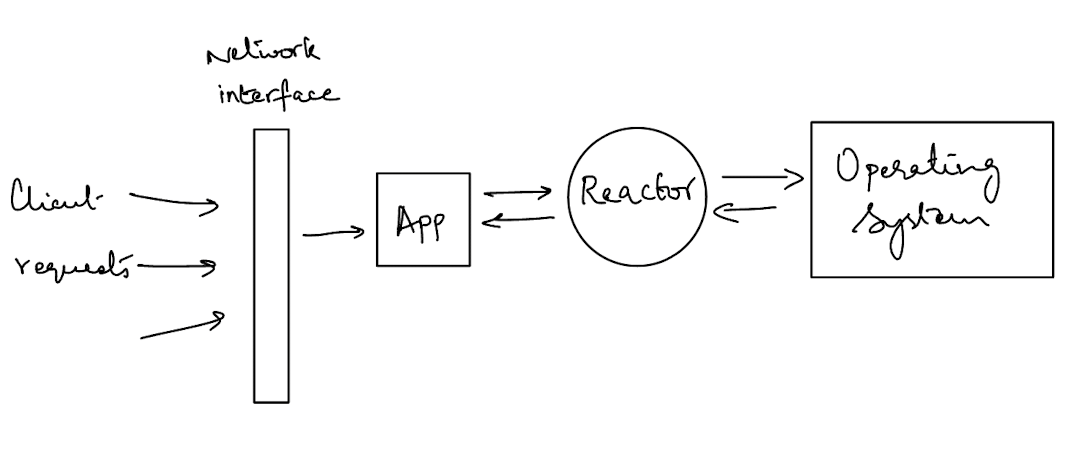

Reactors

Async runtimes have an important component called reactors. These components sit on top of the OS and listen for events from the underlying file descriptors. This is what allows an application to offload a lot of the work.

For instance, consider that your application is listening on a TCP socket. Without an async runtime, you’d typically block on the main thread and listen for connections. Then, as you receive each connection, you’d offload the incoming request onto a separate thread or pass it to a thread pool.

This works fine, but you can make use of certain syscalls to improve your throughput with fewer number of threads (even a single thread).

Let’s start with building a simple reactor.

Another great crate to study would probably be mio which is what Tokio is built on

I’ve used the libc crate to allow a FFI to C so that syscalls can be made. It’s a simple design, just stores the events and has a notification mechanism built on Unix streams.

pub struct Reactor {

kq: RawFd, // the kqueue fd

events: Vec<libc::kevent>,

capacity: usize,

notifier: (UnixStream, UnixStream),

}

The reactor exposes the following API:

addto start watching new file descriptorsdeleteto stop watching file descriptorsnotifyto unblock the reactorpollto ask for events from the OS in a blocking manner

The poll is the most important method because that’s where the blocking routine comes in. To implement this we’re going to have to make use I/O multiplexing systems like kqueue (macOS), epoll(Linux) and IOCP(Windows). This is all part of the “async i/o” umbrella that I’m trying to demystify for myself.

The basic idea behind these interfaces is that you can use a single application level thread to monitor all the I/O sources you are interested in for readiness.

io_uring fell under the same category as the above interfaces, but that's not true. Typically, there are two API styles - readiness based and completion based.

epoll and kqueue fall under the readiness based model. These syscalls only indicate when a file descriptor is available to be read from or written to. There's the overhead of an additional syscall to actually do the writing or reading in this case.

io_uring on the other hand falls under the completion based model. This model involves providing the file descriptors you're interested in reading from or writing to and getting the actual results back. It avoids the overhead of the additional syscall.

One interesting difference is that it makes no sense to use the readiness based model when doing file I/O. It doesn't mean anything to wait for file "readiness" in this case since files are always ready for I/O.

If you are interested in learning more, check out this talk by King Protty

The implementation for the Reactor is provided below.

impl Reactor {

pub fn new() -> std::io::Result<Self> {

let kq = unsafe { libc::kqueue() };

if kq < 0 {

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

let (read_stream, write_stream) = UnixStream::pair()?;

read_stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;

write_stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;

let reactor = Self {

kq,

events: Vec::new(),

capacity: 1,

notifier: (read_stream, write_stream),

};

reactor.modify(

reactor.notifier.0.as_raw_fd(),

Event::readable(reactor.notifier.0.as_raw_fd()),

)?;

Ok(reactor)

}

pub fn add(&mut self, fd: RawFd, ev: Event) -> std::io::Result<()> {

self.modify(fd, ev)

}

pub fn delete(&mut self, fd: RawFd) -> std::io::Result<()> {

self.modify(fd, Event::none(fd))

}

pub fn notify(&mut self) -> std::io::Result<()> {

self.notifier.1.write(&[1])?;

Ok(())

}

fn modify(&self, fd: RawFd, ev: Event) -> std::io::Result<()> {

let read_flags = if ev.readable {

EV_ADD | EV_ONESHOT

} else {

EV_DELETE

};

let changes = [kevent {

ident: fd as usize,

filter: EVFILT_READ,

flags: read_flags,

fflags: 0,

data: 0,

udata: std::ptr::null_mut(),

}];

let result = unsafe {

kevent(

self.kq,

changes.as_ptr(),

1,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

0,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

)

};

if result < 0 {

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

Ok(())

}

pub fn poll(&mut self) -> std::io::Result<Vec<Event>> {

let max_capacity = self.capacity as c_int;

self.events.clear();

let result = unsafe {

self.events

.resize(max_capacity as usize, std::mem::zeroed());

let result = kevent(

self.kq,

std::ptr::null(),

0,

self.events.as_mut_ptr(),

max_capacity,

std::ptr::null(),

);

result

};

if result < 0 {

// return the last OS error

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

let mut mapped_events = Vec::new();

for i in 0..result as usize {

let kevent = &self.events[i];

let ident = kevent.ident;

let filter = kevent.filter;

let mut buf = [0; 8];

if ident == self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd() as usize {

self.notifier.0.read(&mut buf)?;

self.modify(

self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd(),

Event::readable(self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd()),

)?;

}

let mut event = Event {

fd: ident,

readable: false,

writable: false,

};

match filter {

EVFILT_READ => event.readable = true,

EVFILT_WRITE => event.writable = true,

_ => {}

};

self.modify(event.fd as i32, Event::readable(event.fd as i32))?;

mapped_events.push(event);

}

Ok(mapped_events)

}

}

The notify method is an interesting little hack because it writes dummy data into one end of the Unix socket, and because we tell kqueue we are interested in the other end of the stream, we have a way to unblock the kevent syscall in the poll method.

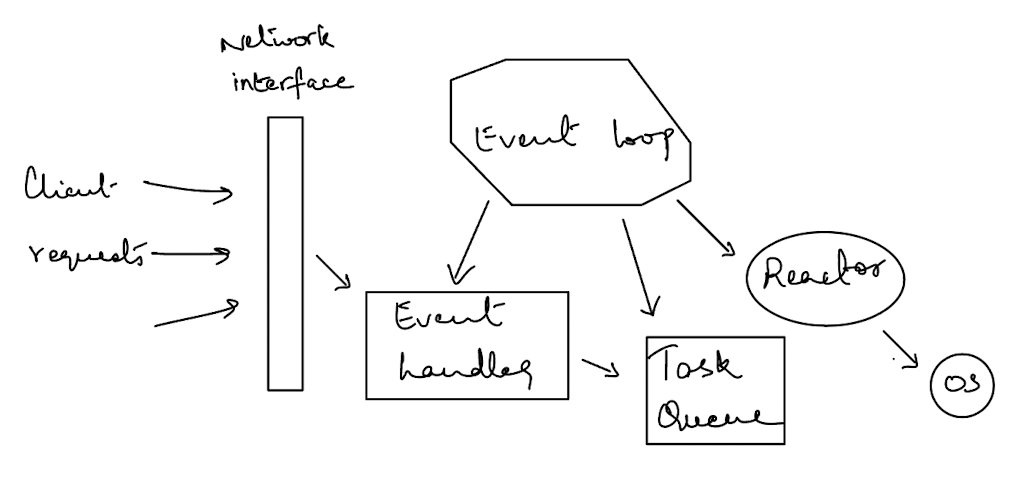

Event Loops

In the previous post, we discussed Executors which were a component responsible for polling futures to completion. In the context of asynchronous I/O, you need an analogous event loop which is constantly monitoring for I/O events and then reacting based on those events.

Let’s build a dead simple event loop which will wait on I/O events and also handle a small set of tasks. To handle the tasks, we’ll create a task queue component and feed that into our event loop to read from.

We’ll have 3 types of tasks - registration tasks, unregistration tasks and scheduled tasks.

The scheduled tasks are a way of some object telling the event loop that it wants to be polled, which is where the Unix pipe hack comes in.

pub struct RegistrationTask {

pub fd: usize,

pub reference: Box<dyn EventHandler>,

}

pub struct UnregistrationTask {

pub fd: usize,

}

pub struct ScheduledTask {

pub fd: usize,

}

pub enum Task {

RegistrationTask(RegistrationTask),

UnregistrationTask(UnregistrationTask),

ScheduledTask(ScheduledTask),

}

impl Display for Task {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

match self {

Task::RegistrationTask(task) => write!(f, "RegistrationTask: fd {}", task.fd),

Task::UnregistrationTask(task) => write!(f, "UnregistrationTask: fd {}", task.fd),

Task::ScheduledTask(task) => write!(f, "ScheduledTask: fd {}", task.fd),

}

}

}

pub struct TaskQueue {

pub queue: Vec<Task>,

}

impl TaskQueue {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Self { queue: Vec::new() }

}

pub fn add_task(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.queue.push(task);

}

}

Now, for the event loop itself.

struct EventLoop {

reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>,

task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>,

references: HashMap<usize, Box<dyn EventHandler>>,

}

I’m using the Box<dyn EventHandler> to hold a reference to the object backing the file descriptor (more on that below).

There is the overhead of dynamic dispatch here but we’re not trying to build a performant system, so that’s okay.

impl EventLoop {

fn new(reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>, task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>) -> Self {

Self {

reactor,

task_queue,

references: HashMap::new(),

}

}

/// Add a reference to the object backing the file descriptor

fn register(&mut self, fd: usize, reference: Box<dyn EventHandler>) {

self.references.insert(fd, reference);

}

/// Remove the reference backing the file descriptor

fn unregister(&mut self, fd: usize) {

self.references.remove(&fd);

}

fn process_tasks(&mut self) {

let mut tasks_to_process = Vec::new();

{

// Collect tasks to process

let mut task_queue = self.task_queue.lock().unwrap();

while let Some(task) = task_queue.queue.pop() {

tasks_to_process.push(task);

}

}

// Process collected tasks

for task in tasks_to_process {

match task {

Task::RegistrationTask(registration_task) => {

self.register(registration_task.fd, registration_task.reference);

}

Task::UnregistrationTask(unregistration_task) => {

self.unregister(unregistration_task.fd);

}

Task::ScheduledTask(scheduled_task) => {

if let Some(reference) = self.references.get_mut(&scheduled_task.fd) {

reference.poll();

}

}

}

}

}

fn handle_events(&mut self, events: Vec<Event>) {

for event in events {

if let Some(reference) = self.references.get_mut(&event.fd) {

reference.event(event);

}

}

}

fn run(&mut self) {

loop {

self.process_tasks();

let events = self

.reactor

.lock()

.unwrap()

.poll()

.expect("Error polling the reactor");

self.handle_events(events);

}

}

}

The most important part of the EventLoop is the run function at the bottom. We do three things here - get the list of tasks on the task queue and take action on them, poll the Reactor for any new events and handle any events that are returned.

When an event is returned, the EventLoop calls the event function on the object backing the file descriptor.

It’s worth it to stop and paint a picture here of what is going on since we’ve added a lot to our runtime in this section.

This is mostly the same as the previous image, except that I’ve expanded on what the application really contains. But there’s still that EventHandler box I haven’t really explained.

EventHandler

This is a really simple part of the system. It’s just some object that handles events. That’s all it is!

The object is expected to conform to some interface like the one below

trait EventHandler {

fn event(&mut self, event: Event);

fn poll(&mut self);

}

Now, what objects do we need to conform to this trait? If we’re setting up a TCP listener, we need the object serving as a listener to conform to that trait, so let’s do that first.

enum AsyncTcpListenerState {

WaitingForConnection,

Accepting(TcpStream),

}

struct AsyncTcpListener {

listener: TcpListener,

fd: usize,

reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>,

task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>,

state: Option<AsyncTcpListenerState>,

}

The AsyncTcpListener is the object backing the TCP server file descriptor. It maintains some internal state to make it easier to encode logic, so let’s look at the implementation.

impl AsyncTcpListener {

fn new(

listener: TcpListener,

reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>,

task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>,

) -> std::io::Result<Self> {

let fd = listener.as_raw_fd();

reactor.lock().unwrap().add(fd, Event::readable(fd))?;

Ok(AsyncTcpListener {

listener,

fd: fd as usize,

reactor,

task_queue,

state: Some(AsyncTcpListenerState::WaitingForConnection),

})

}

}

impl EventHandler for AsyncTcpListener {

fn event(&mut self, event: Event) {

match event.readable {

true => match self.listener.accept() {

Ok((client, addr)) => {

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpListenerState::Accepting(client));

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::ScheduledTask(ScheduledTask { fd: self.fd }));

}

Err(e) => eprintln!("Error accepting connection: {}", e),

},

false => {

panic!("AsyncTcpListener received an event that is not readable")

}

}

}

fn poll(&mut self) {

match self.state.take() {

Some(AsyncTcpListenerState::Accepting(client)) => {

let client = AsyncTcpClient::new(

client,

Arc::clone(&self.reactor),

Arc::clone(&self.task_queue),

)

.unwrap();

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::RegistrationTask(RegistrationTask {

fd: client.fd,

reference: Box::new(client),

}));

}

Some(AsyncTcpListenerState::WaitingForConnection) => {

panic!("The WaitingForConnection state should not be reached in the poll fn for listener")

}

None => {

panic!("No state found in the poll fn for listener")

}

}

}

}

Now, when we receive a connection from the internet, we need to do something similar for each client because we need an object backing the file descriptors for clients as well.

#[derive(Debug)]

enum AsyncTcpClientState {

Waiting,

Reading,

Writing,

Close,

Closed,

}

struct AsyncTcpClient {

client: TcpStream,

fd: usize,

reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>,

task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>,

state: Option<AsyncTcpClientState>,

}

There’s a lot more states but that’s entirely implementation dependent. You could make do with just 2 or 3 states too. It all comes down to how you want to encapsulate the logic.

Now, here’s the implementation for the client

impl AsyncTcpClient {

fn new(

client: TcpStream,

reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>,

task_queue: Arc<Mutex<TaskQueue>>,

) -> std::io::Result<Self> {

let fd = client.as_raw_fd();

reactor.lock().unwrap().add(fd, Event::readable(fd))?;

Ok(Self {

client,

fd: fd as usize,

reactor,

task_queue,

state: Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Waiting),

})

}

}

impl EventHandler for AsyncTcpClient {

fn event(&mut self, event: Event) {

match self.state.take() {

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Waiting) => {

if event.readable {

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Reading);

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::ScheduledTask(ScheduledTask { fd: self.fd }));

}

}

Some(s) => {

self.state.replace(s);

}

None => {

panic!("state was none");

}

}

}

fn poll(&mut self) {

match self.state.take() {

None => {}

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Waiting) => {

panic!("The Waiting state should not be reached in the poll fn for client")

}

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Reading) => {

let reader = BufReader::new(&self.client);

let http_request: Vec<_> = reader

.lines()

.map(|line| line.unwrap())

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.collect();

if http_request

.iter()

.next()

.unwrap()

.contains("GET / HTTP/1.1")

{

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Writing);

} else {

eprintln!("received invalid request, closing the socket connection");

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Close);

}

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Writing);

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::ScheduledTask(ScheduledTask { fd: self.fd }));

self.reactor.lock().unwrap().notify().unwrap();

}

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Writing) => {

let path = Path::new("hello.html");

let content = std::fs::read(path).unwrap();

let response = format!(

"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Length: {}\r\nConnection: close\r\n\r\n{}",

content.len(),

String::from_utf8_lossy(&content)

);

self.client.write_all(response.as_bytes()).unwrap();

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Close);

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::ScheduledTask(ScheduledTask { fd: self.fd }));

self.reactor.lock().unwrap().notify().unwrap();

}

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Close) => {

// remove the client fd from the reactor and unregister from the event loop

self.reactor

.lock()

.unwrap()

.delete(self.fd.try_into().unwrap())

.unwrap();

self.task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::UnregistrationTask(UnregistrationTask { fd: self.fd }));

self.client.shutdown(std::net::Shutdown::Both).unwrap();

self.state.replace(AsyncTcpClientState::Closed);

}

Some(AsyncTcpClientState::Closed) => {}

}

}

}

This looks like a lot of code, but both of these objects are just state machines backing a file descriptor. There’s nothing more to it. The client encapsulates logic in it’s state machine like reading from a file and then writing back to the socket, and the listener only has 2 states - either accepting connections or waiting for new connections.

You could do fancy things with the client like spawning threads when reading from a file to ensure that you don’t block the event loop in any way, but for our experimental purposes this should be good enough.

Each of the objects above implement the EventHandler trait - which means they both have a poll && event method.

The former is called by the event loop when it is scheduled to do so - that is, it gets a task from the task queue telling it to poll a specific object.

The latter is called when the event loop receives a new event for a specific file descriptor. It then calls the object backing that file descriptor.

Wiring It All Up

Okay, we understand each of the components on their own but we need to wire up everything to see how it works together.

fn main() {

let reactor = Arc::new(Mutex::new(Reactor::new().unwrap()));

let task_queue = Arc::new(Mutex::new(TaskQueue::new()));

let mut event_loop = EventLoop::new(Arc::clone(&reactor), Arc::clone(&task_queue));

// start listener

let tcp_listener = TcpListener::bind("127.0.0.1:8000").unwrap();

let listener =

AsyncTcpListener::new(tcp_listener, Arc::clone(&reactor), Arc::clone(&task_queue)).unwrap();

task_queue

.lock()

.unwrap()

.add_task(Task::RegistrationTask(RegistrationTask {

fd: listener.fd,

reference: Box::new(listener),

}));

// start the event loop

event_loop.run();

}

We create all our objects and pass them into the event loop. We then create a TcpListener and construct a backing object on top of it. Next, we push a task into the task queue to register the new file descriptor and it’s backing object with the event loop and we fire off the event loop.

I’m placing the run function of the event loop below again because it’s the central piece of this entire system. When we call process_tasks, the event loop will pick up the RegistrationTask and add the file descriptor and the backing object to it’s references.

Next, it will listen for events from the reactor and act on those events. When it receives an event, it gets it for a specific file descriptor, so it will look up the file descriptor in it’s references, find the backing object and call the object’s event method.

fn run(&mut self) {

loop {

self.process_tasks();

let events = self

.reactor

.lock()

.unwrap()

.poll()

.expect("Error polling the reactor");

self.handle_events(events);

}

}

I mentioned earlier that the scheduled tasks are the way of some object telling the event loop that it wants to be polled, and that’s what the event loop does in the process_tasks method. It just calls the poll method on the underlying object.

fn process_tasks(&mut self) {

let mut tasks_to_process = Vec::new();

{

// Collect tasks to process

let mut task_queue = self.task_queue.lock().unwrap();

while let Some(task) = task_queue.queue.pop() {

tasks_to_process.push(task);

}

}

// Process collected tasks

for task in tasks_to_process {

match task {

Task::RegistrationTask(registration_task) => {

self.register(registration_task.fd, registration_task.reference);

}

Task::UnregistrationTask(unregistration_task) => {

self.unregister(unregistration_task.fd);

}

Task::ScheduledTask(scheduled_task) => {

if let Some(reference) = self.references.get_mut(&scheduled_task.fd) {

reference.poll();

}

}

}

}

}

Now, if you go back and look at the code for the AsyncTcpClient, you’ll see calls to notify on the reactor placed at the end of each state transition. The purpose of that call is for the object to tell the event loop that it needs to be polled because it’s ready to move forward (this is where the Unix pipe hack comes in).

Well, there you have it - a single-threaded async runtime in ~500 lines of code.

I intend to continue the series with another post by trying to hook up my futures and executor with the event loop and reactor. Should be interesting!