RIFL

Introduction

I’ve recently been reading Database Internals by Alex Petrov, and I came across a section title Reusable Infrastructure For Linearizability.

Now, the book itself doesn’t go into much detail about the implementation of RIFL so I got down to reading the paper and an article on another blog about it.

I want to explain this concept in this article because this helps me understand things better.

The Problem

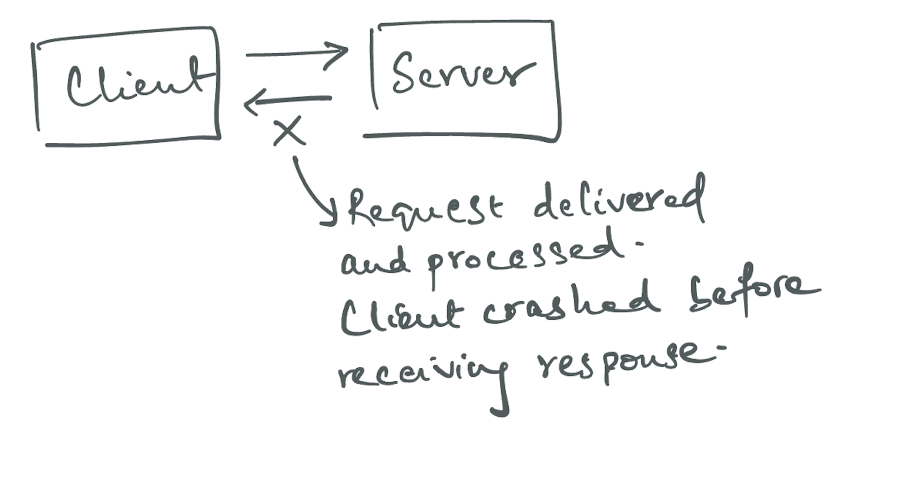

Imagine you have a client and a server. The server can represent anything, a database or a key-value store etc. It doesn’t really matter.

The client makes a request to write something to the server. The server receives the request, processes it and delivers a successful response. However, before the client can receive the response and send an acknowledgement, it crashes. Now, when the client comes back up again, it is going to re-try the request which will lead to the server writing the value again.

This wouldn’t be a big problem if the server was designed with idempotency in mind but that isn’t always the case. Take the classic example of incrementing a counter, it would be incremented twice for the same request in this case.

This problem seems like a variation of the classic two generals problem, which is a pretty famous problem in distributed computing.

What RIFL Is

Now, RIFL is designed to make RPC calls linearizable. This means that if the same RPC call is retried multiple times by a client, the operation itself isn’t carried out multiple times.

This helps ensure that the system remains linearizable so that all clients observing it see the system in the same state after a certain point in time.

It offers a way to upgrade ‘at-least-once’ semantics to ‘exactly once’, which is the holy grail in terms of distributed systems communication.

The Components Of RIFL

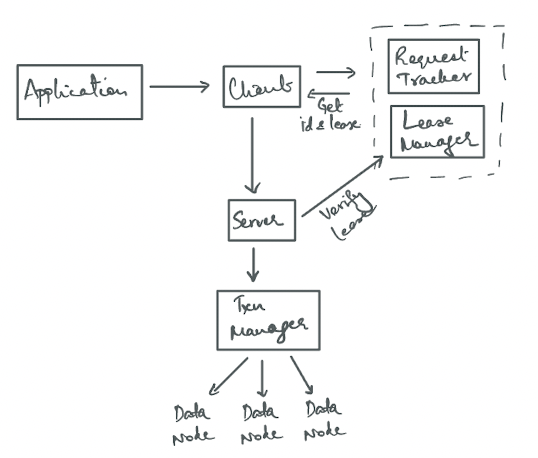

There are three main subsystems in RIFL:

- The Request Tracker Module (runs on clients)

- The Lease Manager Module (runs on clients and servers)

- The Result Tracker Module (runs on servers)

Each of these have a very specific role to play.

Request Tracker

The request tracker generates a unique id per request that comes in to the client.

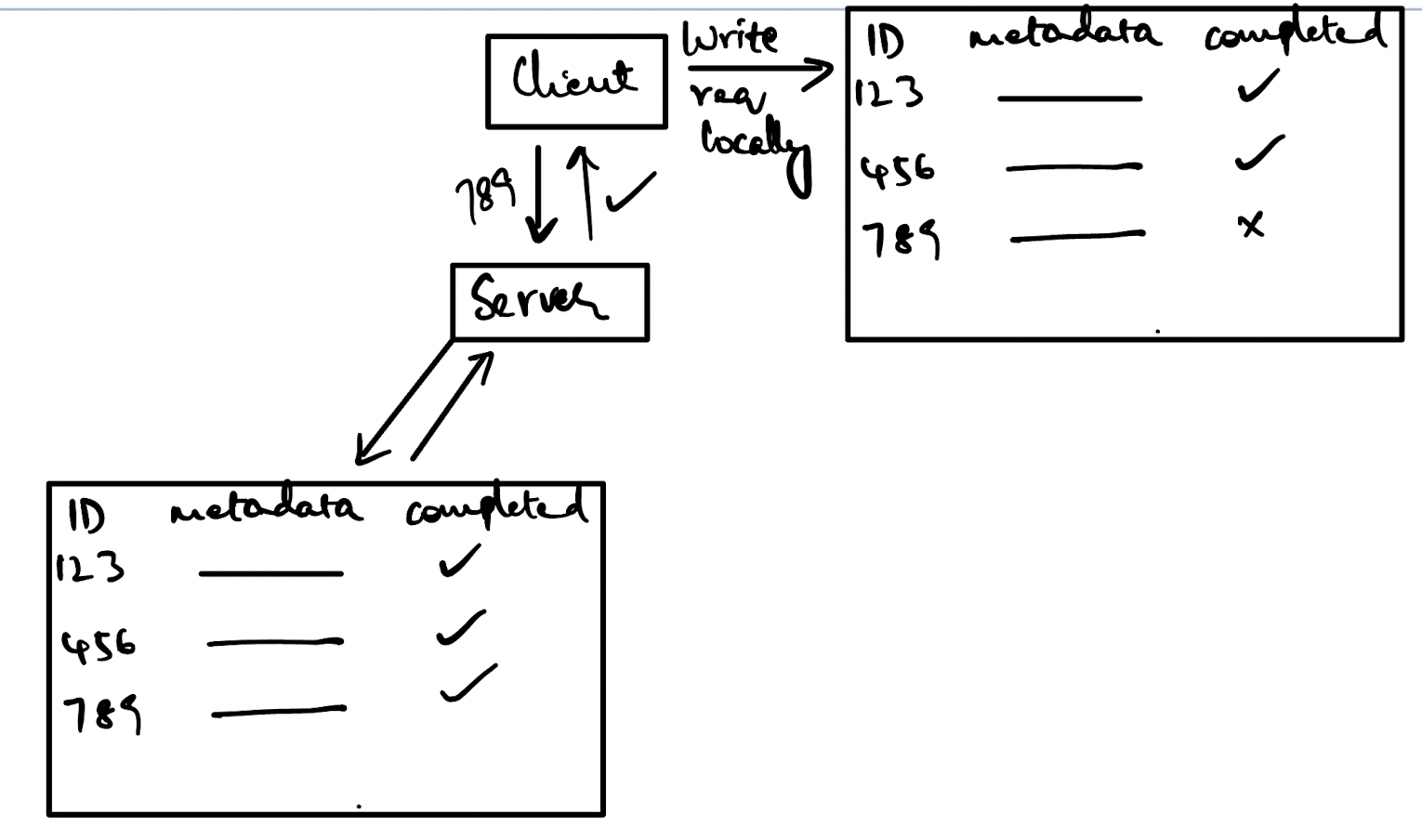

When a new request comes into the client, it generates a unique id for this request and persists it along with some metadata to some form of local storage. It tracks the completion status of this request as part of the metadata.

Lease Manager

The lease manager is a little more interesting. It took a little digging to understand exactly what the purpose of this is.

For every request that comes in, a client must contact the Lease Manager and obtain a lease for the resource it wants to access. The identifier for this lease is the unique identifier for the RPC call. The client is expected to renew this lease within some time period. If the lease for a client expires, the server does not service the request.

Here’s a nice article on leases which can explain the concept in more depth.

Result Tracker

The result tracker module is meant to provide completion records for each request, sometimes called a Completion Object.

Everytime a request is serviced by the server, either successfully or otherwise, it is written to the local persistence store as a Completion Object record. Once the server has sent the response back to the client and received acknowledgement from the client of it’s receipt, it marks the record for garbage collection which runs during the compaction process.

Lifetime Of A Request

The request comes in from an application to a client. Now, the client generates a unique id for this request. In RIFL, identifiers consist of two parts: a 64-bit unique identifier for the client and a 64-bit sequence number allocated by that client.

Next, the request must attain a lease from the Lease Manager module. When a server receives a request, it checks if the lease is still valid by contacting the Lease Manager. If the lease is nearing expiration, the Lease Manager checks if the client is still reachable, and if it is, the lease is renewed. If the client is unreachable, the lease is allowed to expire.

Now, assuming the lease has been validated by the server, it is free to carry out the transaction required by the request. It typically does this by following a 2PC protocol. Before running this protocol, it first inserts a completion record for this request indicating the current status of the request. This completion record is identified by the request’s unique identifier.

Assuming, the request is completed successfully and the client acknowledges receipt, the completion record can be marked as completed and garbage collected later.

Failure Scenarios

The classic failure scenario is where the client sends a request which is successfully served by the server, but the client crashes either:

- Before receiving the response from the server

- Before acknowleding receipt from the server

Let’s take a simple example of an e-commerce application. Assume that we are managing the state of a cart. Now, the application issues a request to the client to ADD(eggs, cart) which will add eggs to a cart.

The client issues this request to the server and then crashes before receiving and acknowledging a response.

Now, when the client restarts, it will notice that it has a request locally persisted which has not been completed. It will retry this request with the same request id.

The server receives this request and uses the request id as a lookup to see if it has already been serviced. Assuming it has already been serviced, the server will not perform the operation again but will instead return a successful response to the client.

The client will then update it’s local store to mark the request as completed and send it’s acknowledgement to the server. Upon receipt of the acknowledgement, the server will mark the record as acknowledged and mark it for garbage collection.

Conclusion

Reading about RIFL was pretty interesting and I’d highly recommend reading the paper itself.

RIFL attempts to first build a linearizable layer upon which to execute transactions. However, despite the failure scenarios it handles, it depends on the client being reliable enough that it first records and persist the request it is making before issuing it.

And what happens if a client one level up crashes immediately after issuing the request? Then that layer would require linearizability. The paper has a section which addresses this.

There is also a section on performance in the paper that is worth checking out.