2PC

Introduction

Continuing on with stuff I’ve read in Database Internals by Alex Petrov, I wanted to look at 2PC today.

This is a fairly common approach to handling distributed transactions so this will be a fairly short blog post. I used this as more of an exercise to write some Go code for the very first time more than anything else.

Problem

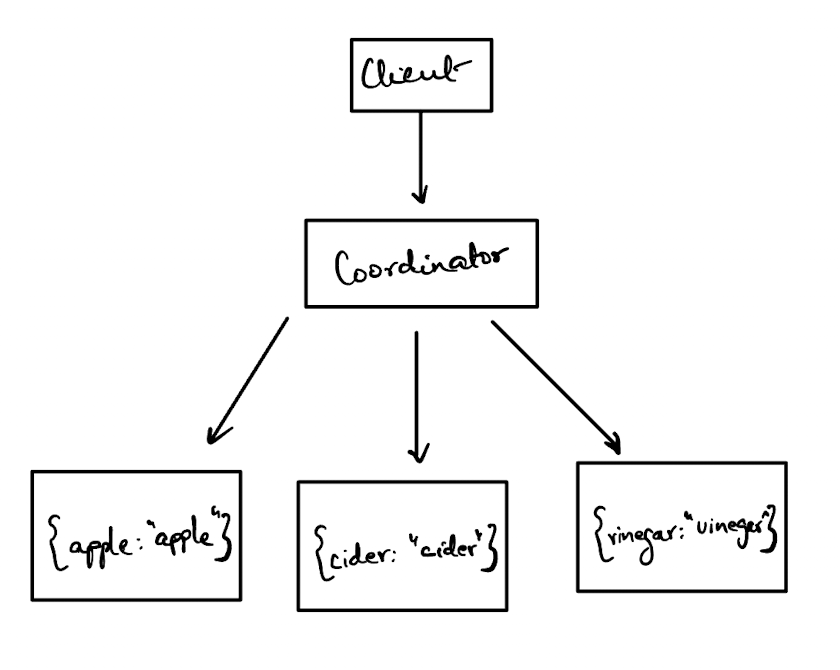

Imagine you have a distributed key value store. I love taking the example of a distributed key value store because it’s simple enough to understand that you don’t get lost in the weeds of trying to figure out the system you’re building 2PC for and just focus on 2PC itself.

Our key value store is just going to be a map of type map[string]string and these maps will be split across multiple nodes.

Each of our nodes can hold some subset of the overall data that we want. However, may or may not be replicated across multiple nodes. So, in situations where we want to modify the value of a key value pair, we would need to do it across all instances where that pair is present. It should update all of them atomically or not at all.

What 2PC Does

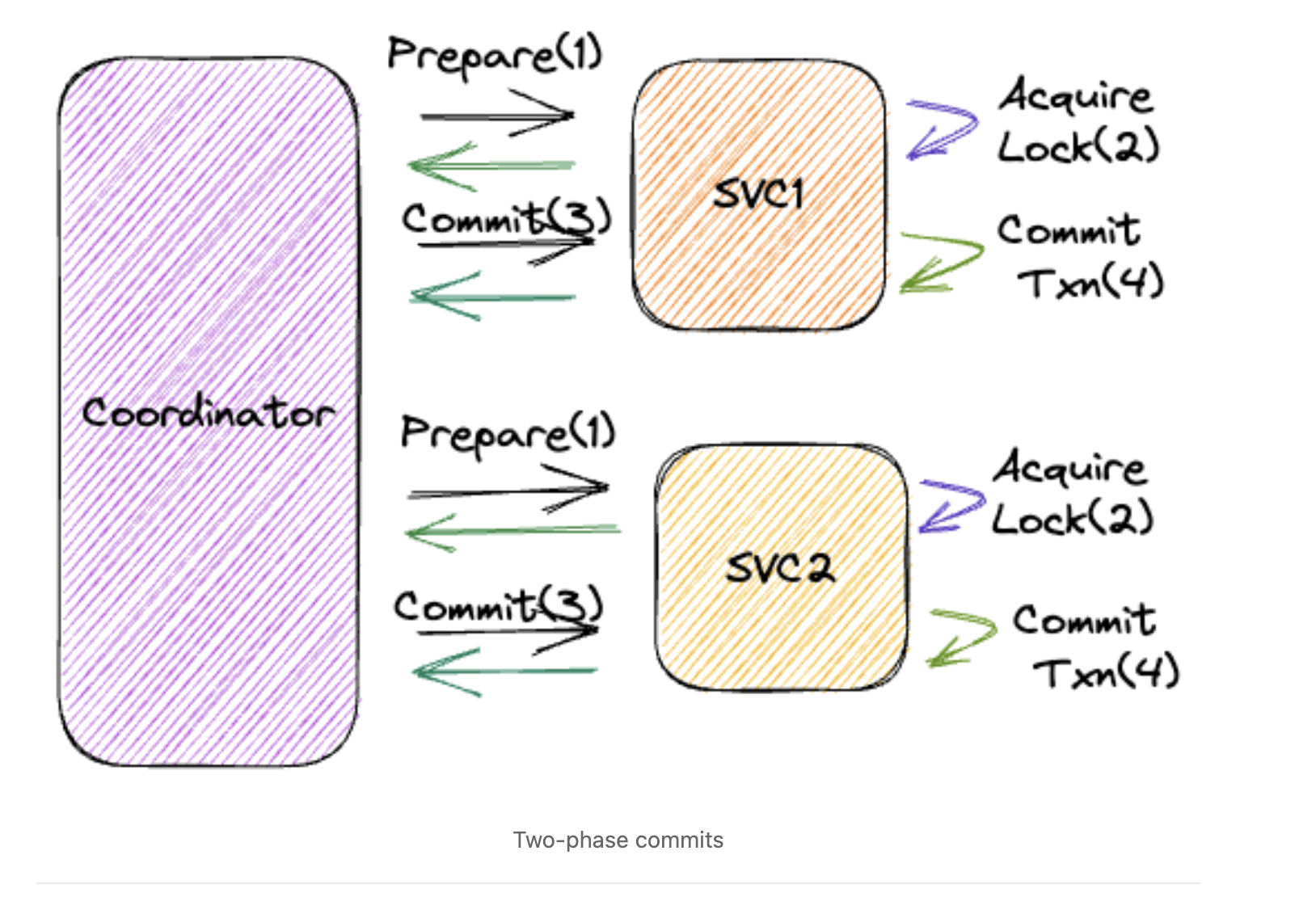

2 phase commit is really simple to understand. It’s called 2 phase because there’s literally 2 phases in it - a prepare phase and a commit phase.

There are two main components involved in 2PC - the coordinator and the participants. There can only be one coordinator and there can be any number of participants.

The prepare phase involves sending out a message to prepare for the transaction from the coorindator and waiting for a response from them. If the coordinator gets a successful response from all the participants, it sends out a message telling participants to commit the transaction.

Some Rough Code

I like writing code to explore how something actually works because it helps solidify certain concepts.

type Message string

const (

Prepare Message = "PREPARE"

VoteCommit = "VOTE_COMMIT"

VoteAbort = "VOTE_ABORT"

Commit = "COMMIT"

Abort = "ABORT"

)

type Coordinator struct {

participants []*Participant

}

type Participant struct {

index int

data map[string]string

locks map[string]bool

}

func NewParticipant(index int) *Participant {

return &Participant{

index: index,

data: make(map[string]string),

locks: make(map[string]bool),

}

}

So, we have a few different structs - one for the coordinator and one for the participants. We also have a way to create a new participant because each of them needs to hold some data.

Okay, now we just need to fire off a transaction and see if that can be successfully completed or not.

func (c *Coordinator) initiateTransaction(oldValue string, newValue string) {

// Phase 1: Prepare Phase

for _, participant := range c.participants {

msg := participant.prepare(oldValue, newValue)

if msg == VoteAbort {

c.abortTransaction(oldValue, newValue)

return

}

}

// Phase 2: Commit Phase

c.commitTransaction(oldValue, newValue)

}

func main() {

data := []string{"apple", "banana", "cherry", "date", "fig"}

participants := make([]*Participant, len(data))

for i, value := range data {

participants[i] = NewParticipant(i)

participants[i].data[value] = value

}

coordinator := &Coordinator{

participants: participants,

}

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

coordinator.initiateTransaction("apple", "APPLE")

}()

wg.Wait()

}

We fire off a single transaction that tries to rewrite apple to APPLE within a goroutine.

For each transaction that is fired off the coordinator checks with each participant if it can fulfil this transaction or not.

If it can’t, the coordinator gives up on the whole transaction. If it can, it sends out a message indicating that the transaction can indeed be committed.

Drawbacks

-

2PC is a blocking protocol. This means that if a participant is down, the whole transaction is blocked until it comes back up. This is a pretty big drawback because it means that the whole system is only as reliable as the least reliable participant.

-

2PC is also a synchronous protocol. This means that the coordinator has to wait for a response from all participants before it can move on to the next phase. This can be a problem if the participants are geographically distributed and the latency between them is high.

-

2PC also has a single point of failure because if the coordinator ever goes down at any point, the transaction will either fail or even worse the transaction might go into an inconsistent state.

Conclusion

So, that’s 2PC in a nutshell. A really simple protocol which actually has massive adoption because of the ease of implementation.

There is a better version of this called 3 phase commit which I’ll explore in another article.

If you want to find the full version of the code for 2PC, look here