Linearizability vs Serializability

These two terms - serializability and linearizability are very confusing to me. And not just because of their spellings!

They seem to come from two different domains - linearizability comes from the world of distributed computing and serializability comes from the world of ANSI SQL.

However, since databases themselves are distributed systems now, these two terms tend to get conflated (especially in my head). I watched a recent video of Martin Kleppman give a talk on transactions here and throughout the talk I couldn’t help but wonder why serializability is the highest standard of isolation in the SQL standard

But, that makes sense because linearizability itself has nothing to do with the SQL standard.

Let’s dive in.

There is a great article here which covers the same topic

Linearizability

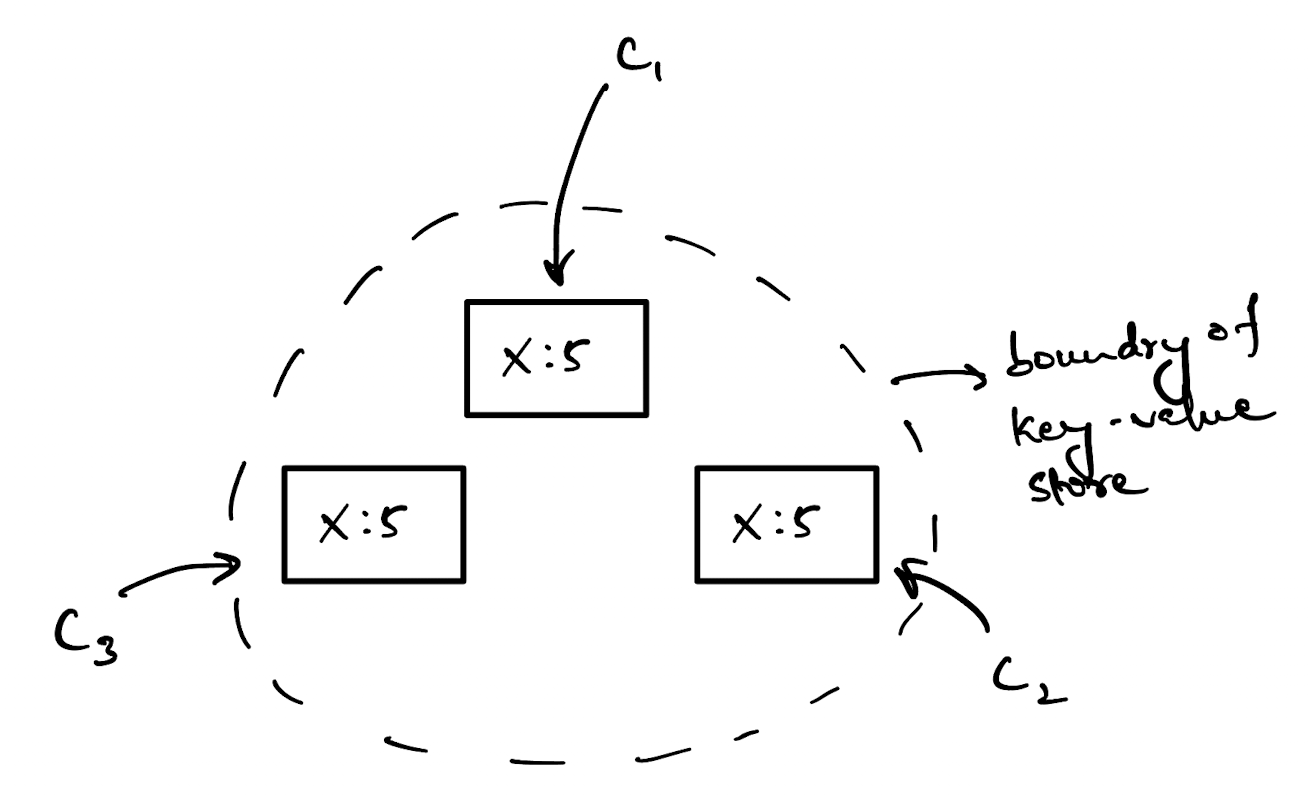

Let’s imagine a distributed key value store. The key of note for us here is x.

We have multiple clients that connect to this distributed key value store and try to read the value of x from different nodes. All of the reads from different clients will return the same value, which is good because this means our system is consistent.

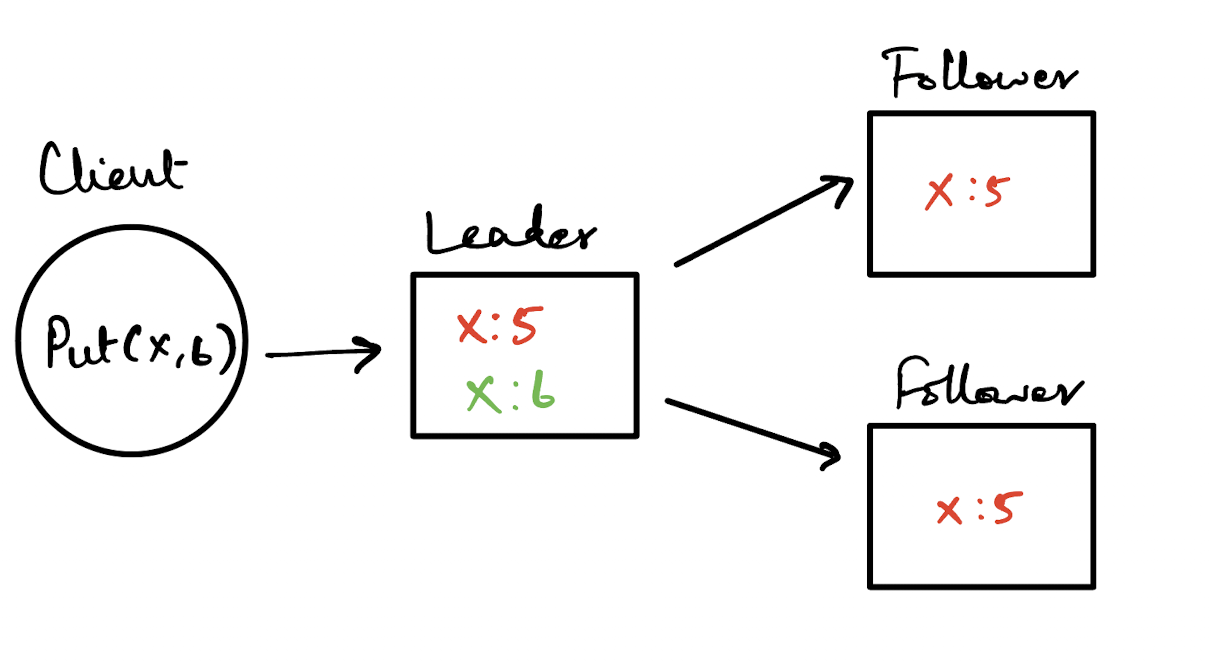

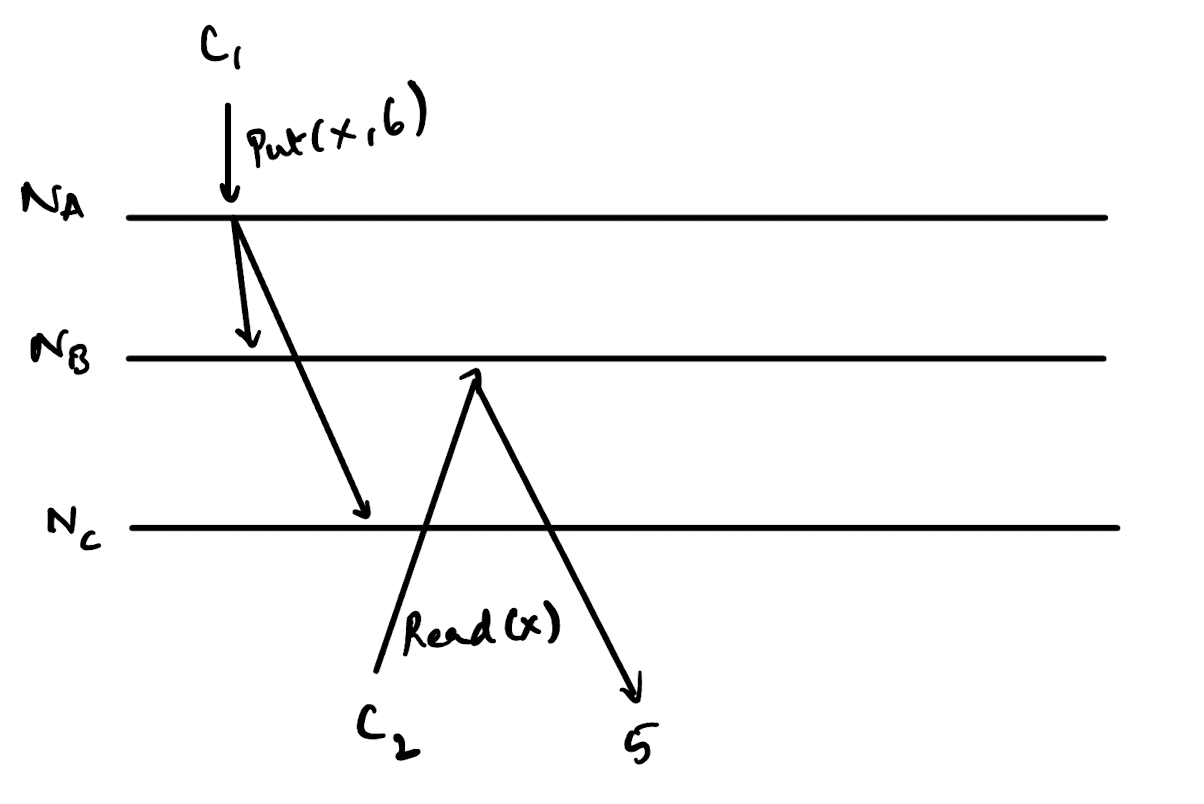

Now, let’s say one of the clients updates the value of x from 5 to 6 via a PUT method. Now, for writes to occur, it will go to one of the nodes and for the duration of this write’s execution and replication, that node will act as a ‘leader’ for the write.

Let’s say the write happens successfully on the leader node and immediately after another client tries to read the value of x from one of the other nodes. This will return 5, which is incorrect.

Therefore, this system is not linearizable because there is no point in time demarcating when the value of x changed from 5 to 6 across the system.

Instead of the leader node acknowledging the write immediately after storing it locally, if it had first replicated the write across the other nodes, the system would have been linearizable.

The point in time at which the value of x changed from 5 to 6 in the system would be called the linearization point. If all changes to any object are done in a linearized manner, it is possible to build a linearizable history of that object (in our case x). Since we have a linearizable history for each object, it is also possible to have a global order of all operations based on the wall-clock time of each operation.

Serializability

This is one of the isolation levels in the ACID acronym defined as part of the ANSI SQL standard. So, typically, serializability is used in the context of transactions in a SQL database.

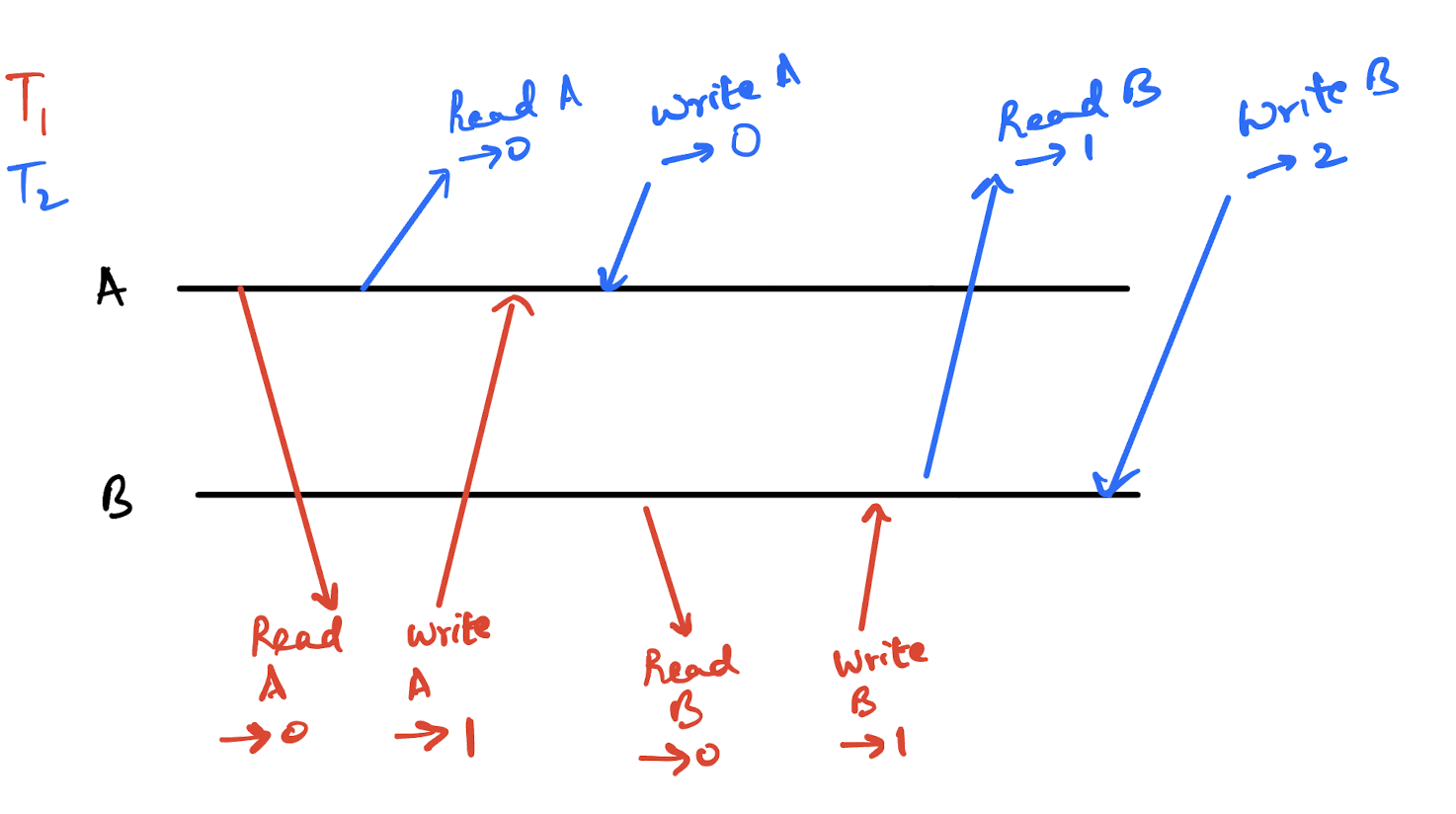

Imagine a database with two values - A & B. The initial value of both these variables is 0.

Now, there are two concurrent transactions operating on the database - T1 & T2.

These two transactions do slightly different things

T_1will increment the value of A & B by 1T_2will double the value of A & B

Since these transactions are concurrent, the order of operations can be very different. If we were to decide to serially execute these transactions, then first only T_1 would run and only after T_1 finishes would T_2 run. This would result in the values of A=2 and B=2

However, this would seriously limit the throughput of the system.

Another option is to allow the operations to interleave in random order like in the image below. However, the issue with this approach is that the outcome of the transaction would not be correct.

For any set of concurrently occurring transactions, there can be multiple possible serializable histories. As long as these histories result in the same outcome, they are valid. What is a valid outcome? The outcome that would result if you were to run these transactions serially - that is one after another.

In our case, as long as any order of operations result in A=2 and B=2 that would be a valid serializable history.

Number Of Possible Histories

I have no idea if this is accurate but I wanted to give this a shot. How many possible histories can there be for the transactions listed above.

There are four steps in each transaction - two involved with reading the values of A & B and two involved with writing the values of A & B. This gives us a total of 8 steps.

The total possible permutations of this is 8! = 40,320

However, some steps require an ordering. A & B have to be read before being written by both transactions. There are two possible ways to order the read and write for each value so this would be 2! permutations and there are four of these sets.

Then, we have 8!/(2! * 2! * 2! * 2!) = 2,520

Again, I have no idea if this calculation is correct (permutations and combinations has always been my weak point) but I thought this was an interesting exercise.

Each of these 2,520 possibitilies is an execution history but not all of them are serializable histories since they don’t necessarily result in a valid outcome.

Distributed Systems And Databases

I believe the point of confusion for me came from conflating distributed systems and databases. Databases are not necessarily distributed systems but they can be.

Earlier, I thought of serializability that was achieved on a single node and linearizability that was achieved across multiple nodes. However, this is the wrong mental model since transactions are also capable of running across multiple nodes.

Instead, it is better to think of consistency in ACID and CAP as separate. Serializability helps maintain the C in ACID and linearizability helps maintain the C in CAP.