Build You A Raft - Part I

What Is Raft?

Before starting, if you just want to look at the full code, go here

Raft is a famous distributed consensus algorithm which is implemented in various database engines now. The most famous is probably Yugabyte DB, a distributed SQL database.

First, we need to discuss what a distributed SQL database is and why we need distributed consensus on it. There are two classic concepts that come to mind when thinking of a distributed database - replication and sharding. Typically when you think of distributed consensus, its for a replicated database. That is, each copy of the database is identical.

Now, imagine that we have a distributed replicated SQL database with 3 nodes. Now there’s two ways to accept a write - any node can accept a write the way Amazon’s Dynamo does from its famous 2007 paper, or a single node is elected a leader and accepts a write and replicates it to the followers. It’s the second case a protocol like Raft was designed for.

The Raft Paper

The Raft paper was published in 2014, and you can read it here. It’s probably one of the more understandeable papers out there and can be grokked pretty easily. Accompanying the paper are two resources - the great Raft website and the even better Raft visualisation. The visualisation is seriously incredible!

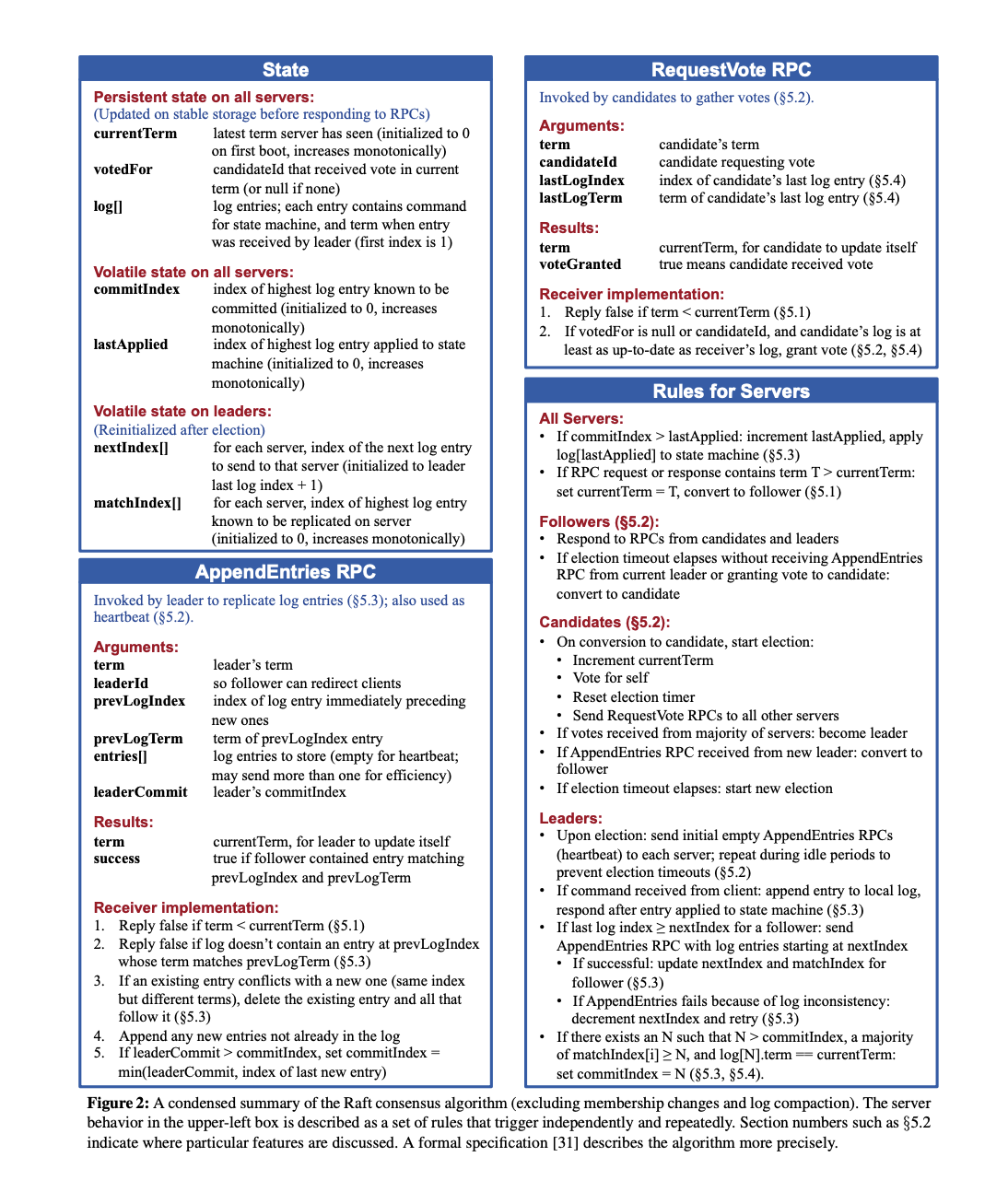

The most important part of the paper is in a single page where the RPC’s are described in detail. This page is dense with information and I spent weeks poring over it, trying to understand what was going on.

Another super valuable resource is the TLA+ spec for Raft. This makes a world of difference if you’re trying to implement Raft.

If you’ve heard of Paxos, Raft is a simpler form of that. Let’s dive into the code!

Defining The Basic Structure

Note: Before diving into the code, I want to emphasize that I do not have a formally correct specification because I haven’t run it against a formal test suite. I only have my own tests that I’ve run it against. Also, this was my first time writing anything significant in Rust, so excuse any poor code habits.

First, we define the basic structure for our node

struct RaftNodeState<T: Serialize + DeserializeOwned + Clone> {

// persistent state on all servers

current_term: Term,

voted_for: Option<ServerId>,

log: Vec<LogEntry<T>>,

// volatile state on all servers

commit_index: u64,

last_applied: u64,

status: RaftNodeStatus,

// volatile state for leaders

next_index: Vec<u64>,

match_index: Vec<u64>,

// election variables

votes_received: HashMap<ServerId, bool>,

election_timeout: Duration,

last_heartbeat: Instant,

}

struct RaftNode<T: RaftTypeTrait, S: StateMachine<T>, F: RaftFileOps<T>> {

id: ServerId,

state: Mutex<RaftNodeState<T>>,

state_machine: S,

config: ServerConfig,

peers: Vec<ServerId>,

to_node_sender: mpsc::Sender<MessageWrapper<T>>,

from_rpc_receiver: mpsc::Receiver<MessageWrapper<T>>,

rpc_manager: CommunicationLayer<T>,

persistence_manager: F,

clock: RaftNodeClock,

}

Each raft node has its own state that it needs to maintain. I’ve segregated this state based on whether its volatile, non-volatile (must be persisted) or is required only for a specific node state. The state is behind a mutex to allow access to it from multiple threads. Typically, you have a node listening for messages on a separate thread and invoking whatever RPC is required and you have the main thread of the node that is doing whatever operations it needs to do. In my test implementations I run everything off a single thread rather than putting the node behind an Arc::mutex interface.

Each node also has a state machine attached to it. This state machine is a user provided state machine, it could be a database or a key value store etc. There needs to be one method on the state machine called apply() or some variant that the cluster calls to update the state machine.

Now, nodes communicate with each other via JSON-over-TCP in my implementation. So, we need to set up the communication channel for them. I did this by defining an RPC manager which is then provided to each node.

struct RPCManager<T: RaftTypeTrait> {

server_id: ServerId,

server_address: String,

port: u64,

to_node_sender: mpsc::Sender<RPCMessage<T>>,

is_running: Arc<AtomicBool>,

}

The RPC manager has a few different methods defined on it - the constructor, a method to start, a method to stop and a function to allow a node to indicate to the manager that it wants to send a message to another node called send_message.

All messages between nodes are serialized to JSON and deserialized from JSON using the serde crate (Note: This obviously isn’t a practical implementation because typically you’d use your own protocol to avoid overhead).

Here’s an implementation of what the send_message function looks like

/**

* This method is called from the raft node to allow it to communicate with other nodes

* via the RPC manager.

*/

fn send_message(&self, to_address: String, message: MessageWrapper<T>) {

info!(

"Sending a message from server {} to server {} and the message is {:?}",

message.from_node_id, message.to_node_id, message.message

);

let mut stream = match TcpStream::connect(to_address) {

Ok(stream) => stream,

Err(e) => {

panic!(

"There was an error while connecting to the server {} {}",

message.to_node_id, e

);

}

};

let serialized_request = match serde_json::to_string(&message.message) {

Ok(serialized_message) => serialized_message,

Err(e) => {

panic!("There was an error while serializing the message {}", e);

}

};

if let Err(e) = stream.write_all(serialized_request.as_bytes()) {

panic!("There was an error while sending the message {}", e);

}

}

Communication between the node and the RPC manager is handled via an MPSC channel in Rust. The receiver stays with the node and the transmitter is with the RPC manager.

Next, let’s dive into the functionality of a Raft cluster. Rather than focusing on each individual RPC function, I’ll go through RPC’s from the perspective of leader election and appending entries to the cluster.

Log Entry

A quick aside before jumping into the RPC’s themselves. We first need to discuss what a log entry itself looks like. Each log entry has the following structure. The most important fields here are term (explained below) and index (a 1-based index).

The LogEntryCommand represents state machine related terminology. So here, it can be either Set or Delete.

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

enum LogEntryCommand {

Set = 0,

Delete = 1,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

struct LogEntry<T: Clone> {

term: Term,

index: u64,

command: LogEntryCommand,

key: String,

value: T,

}

Leader Election

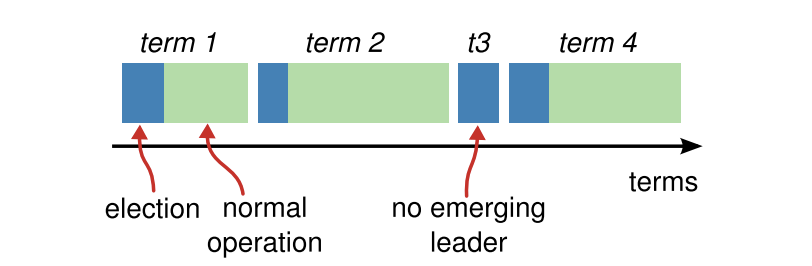

This is a core part of the Raft protocol. This allows a leader to be elected in each term or epoch of a Raft cluster. A term is a time period during which one leader reigns. When a new node wants to be elected leader, it needs to increment the term and ask for a vote. So, something akin to a logical clock.

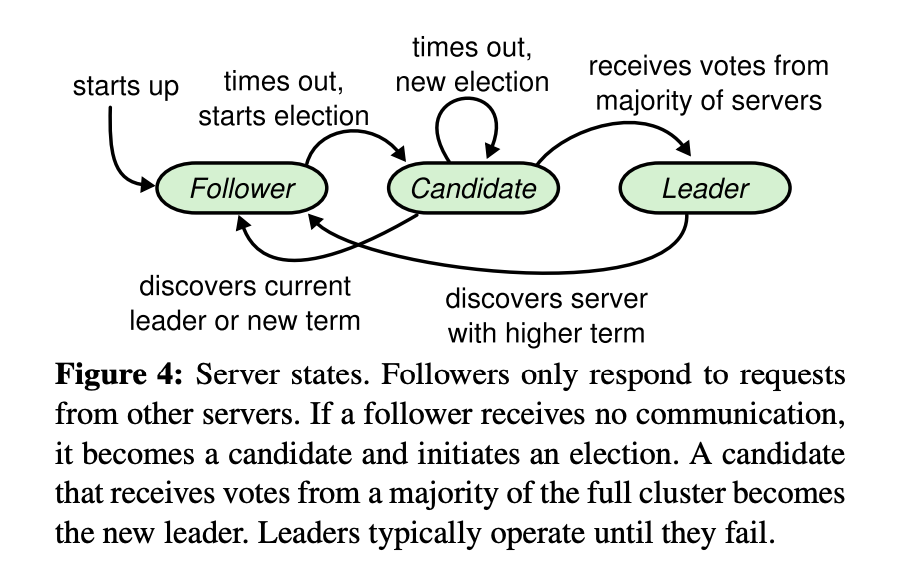

There are 3 possible states every node can be in - a follower, a candidate or a leader. A candidate is just an intermediate state between a follower and a leader. Typically, nodes don’t stay in this state for very long.

There is also the concept of 2 timeouts in Raft - the election timeout and the heartbeat timeout. When these timeouts occur, there are certain state transitions that must occur. The image below is a good representation of that.

As an aside, if you’re curious why timeouts are required, look at the FLP section of this page. The FLP impossibility theorem is based on a famous paper from 1985. There is a generalisation of this theorem called the two generals problem which is fun to learn about.

Next, we need something to represent what a node is supposed to do as time passes. We’ll call this a tick function.

This tick function is something that the Raft cluster does every logical second. I say logical second because in a test cluster you typically want to control the passage of time to be able to create certain test scenarios.

fn tick(&mut self) {

let mut state_guard = self.state.lock().unwrap();

match state_guard.status {

RaftNodeStatus::Leader => {

// the leader should send heartbeats to all followers

self.send_heartbeat(&state_guard);

}

RaftNodeStatus::Candidate | RaftNodeStatus::Follower => {

// the candidate or follower should check if the election timeout has elapsed

self.check_election_timeout(&mut state_guard);

}

}

drop(state_guard);

// listen to incoming messages from the RPC manager

self.listen_for_messages();

self.advance_time_by(Duration::from_millis(1));

}

Here, if a node a is a candidate or a follower, it checks if the current election timeout has elapsed. If it has, it starts an election or restarts an election (if candidate).

If the node is a leader, however, it sends out something called a heartbeat. This is to ensure that the follower nodes don’t believe the leader has died and try to start a new election.

Let’s look at the RPC’s associated with leader election

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

struct VoteRequest {

request_id: u16,

term: Term,

candidate_id: ServerId,

last_log_index: u64,

last_log_term: Term,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

struct VoteResponse {

request_id: u16,

term: Term,

vote_granted: bool,

candidate_id: ServerId

}

For now, focus on the fields term, last_log_index and last_log_term. These are the fields that a node will use to determine whether its vote can be granted or not. The node that is starting an election will send out messages from itself to other nodes and will send the term and the index of its last log entry.

Imagine 2 nodes A and B where A is requesting a vote from B. If B has a higher term, this means that B is further ahead in the cluster’s time period and therefore it cannot accept A as a leader.

Furthermore, if B has a log entry with an index or term greater than the one sent by A in the request, the vote is rejected. Here’s the relevant part of the code

// this node has already voted for someone else in this term and it is not the requesting node

fn handle_vote_request(&mut self, request: &VoteRequest) -> VoteResponse {

// Code removed for brevity

if state_guard.voted_for != None && state_guard.voted_for != Some(request.candidate_id) {

debug!("EXIT: handle_vote_request on node {}. Not granting the vote because the node has already voted for someone else", self.id);

return VoteResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

vote_granted: false,

candidate_id: self.id,

};

}

let last_log_term = state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.term);

let last_log_index = state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index);

let log_check = request.last_log_term > last_log_term

|| (request.last_log_term == last_log_term && request.last_log_index >= last_log_index);

if !log_check {

return VoteResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

vote_granted: false,

candidate_id: self.id,

};

}

// Code removed for brevity

}

Assuming that node B has not granted its vote for anyone in the current election cycle and the log check passes, it can return a successful vote response to A.

Now, let’s look at how vote responses are handled on the requesting node.

/// The quorum size is (N/2) + 1, where N = number of servers in the cluster and N is odd

fn quorum_size(&self) -> usize {

(self.config.cluster_nodes.len() / 2) + 1

}

fn can_become_leader(&self, state_guard: &MutexGuard<'_, RaftNodeState<T>>) -> bool {

let sum_of_votes_received = state_guard

.votes_received

.iter()

.filter(|(_, vote_granted)| **vote_granted)

.count();

let quorum = self.quorum_size();

sum_of_votes_received >= quorum

}

fn handle_vote_response(&mut self, vote_response: VoteResponse) {

let mut state_guard = self.state.lock().unwrap();

if state_guard.status != RaftNodeStatus::Candidate {

return;

}

if !vote_response.vote_granted && vote_response.term > state_guard.current_term {

// the term is different, update term, downgrade to follower and persist to local storage

state_guard.current_term = vote_response.term;

state_guard.status = RaftNodeStatus::Follower;

match self

.persistence_manager

.write_term_and_voted_for(state_guard.current_term, Option::None)

{

Ok(()) => (),

Err(e) => {

error!("There was a problem writing the term and voted_for variables to stable storage for node {}: {}", self.id, e);

}

}

return;

}

// the vote wasn't granted, the reason is unknown

if !vote_response.vote_granted {

return;

}

// the vote was granted - check if node achieved quorum

state_guard

.votes_received

.insert(vote_response.candidate_id, vote_response.vote_granted);

if self.can_become_leader(&state_guard) {

self.become_leader(&mut state_guard);

}

}

This part of the code shows a node receiving a vote and checking whether the sum of votes it has received so far exceeds the quorum required. A quorum is a majority of the nodes (which is why you typically run an odd number of nodes in a Raft cluster. I actually don’t know if you can run an even number of nodes because I don’t think the quorum calculations would work).

Now, once a leader has been elected it needs to ensure it stays the leader and it does via a mechanism called heartbeats. Essentially it sends a network request to every follower once every x number of milliseconds to ensure that the followers don’t start a new election. Here’s the implementation.

fn send_heartbeat(&self, state_guard: &MutexGuard<'_, RaftNodeState<T>>) {

if state_guard.status != RaftNodeStatus::Leader {

return;

}

for peer in &self.peers {

if *peer == self.id {

// ignore self referencing node

continue;

}

let heartbeat_request = AppendEntriesRequest {

request_id: rand::thread_rng().gen(),

term: state_guard.current_term,

leader_id: self.id,

prev_log_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

prev_log_term: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.term),

entries: Vec::<LogEntry<T>>::new(),

leader_commit_index: state_guard.commit_index,

};

let message = RPCMessage::<T>::AppendEntriesRequest(heartbeat_request);

let to_address = self.config.id_to_address_mapping.get(peer).expect(

format!("Cannot find the id to address mapping for peer id {}", peer).as_str(),

);

let message_wrapper = MessageWrapper {

from_node_id: self.id,

to_node_id: *peer,

message,

};

self.rpc_manager

.send_message(to_address.clone(), message_wrapper);

}

}

The heartbeat request is just an AppendEntry request (more on that below).

Now, an interesting question is how do we decide what the value of x should be above. The raft paper mentions that the time it takes for a leader to broadcast its heartbeats to all followers should be an order of magnitude less than the election timeout. The following excerpt is from the paper

Leader election is the aspect of Raft where timing is most critical. Raft will be able to elect and maintain a steady leader as long as the system satisfies the following timing requirement: broadcastTime ≪ electionTimeout ≪ MTBF In this inequality broadcastTime is the average time it takes a server to send RPCs in parallel to every server in the cluster and receive their responses; electionTimeout is the election timeout described in Section 5.2; and MTBF is the average time between failures for a single server. The broadcast time should be an order of magnitude less than the election timeout so that leaders can reliably send the heartbeat messages required to keep followers from starting elections

So, this leads me to conclude that the heartbeat timeout must be an experimental value based on the individual configuration of the cluster you are running. For my setup, I used a heartbeat interval of 50ms. Because I am running a test cluster which works on a single server, this value just needs to be long enough to allow nodes to send RPC messages to other nodes via TCP sockets via the loopback interface.

Log Replication

Now, we come to the more challenging part of the protocol - log replication. First, we’ll tackle log replication on easy mode which assumes no failures

The happy path of log replication is fairly simple to understand. Let’s get the basic structures out of the way first. This is what the request and response looks like

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

struct AppendEntriesRequest<T: Clone> {

request_id: u16,

term: Term,

leader_id: ServerId,

prev_log_index: u64,

prev_log_term: Term,

entries: Vec<LogEntry<T>>,

leader_commit_index: u64,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

struct AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: u16,

server_id: ServerId,

term: Term,

success: bool,

match_index: u64,

}

There’s a couple of new fields here which are important - leader_commit_index in the request and match_index in the follower. Trying to accurately parse what these variables do took me days but its actually quite simple. To accurately explain this, let me first explain the state a leader maintains.

On election, a leader initialises the following variables in its state - next_index and match_index, both of which are uint vectors and maintain an index value for each follower. The next_index represents the next log entry the leader is going to try and replicate and the match_index represents the log entry up to which the leader knows each follower has replicated the entries. So, next_index must stay ahead of match_index, that’s one of the invariants of the Raft state machine.

Now, when a leader sends out an AppendEntry RPC to each follower, the follower responds with a match_index indicating up to where it has replicated the log and the leader_commit_index is used by the leader to determine which log entries can be applied to its own state machine. Once these entries are applied to the state machine, the leader updates the leader_commit_index.

With every request the leader sends out, it includes the leader_commit_index so that followers can know which logs they can commit to their own state machine. This is an important invariant to maintain because once a log entry has been committed to a state machine it can never be revoked. This is an important safety property of Raft.

Okay, let’s look at some code. First, we’ll look at the easier case of a leader node getting a successful response back from a follower.

When a response comes in from a follower, if the response was successful, the leader checks what the match_index the follower sent was. It updates its own state to that value and checks which is the maximum value among its followers that has quorum. It is allowed to commit this value to its own state machine and update its own commit index.

fn handle_append_entries_response(&mut self, response: AppendEntriesResponse) {

let mut state_guard = self.state.lock().unwrap();

if state_guard.status != RaftNodeStatus::Leader {

return;

}

let server_index = response.server_id as usize;

if !response.success {

// reduce the next index for that server and try again

state_guard.next_index[server_index] = state_guard.next_index[server_index]

.saturating_sub(1)

.max(1);

self.retry_append_request(&mut state_guard, server_index, response.server_id);

return;

}

// the response is successful

state_guard.next_index[(response.server_id) as usize] = response.match_index + 1;

state_guard.match_index[(response.server_id) as usize] = response.match_index;

self.advance_commit_index(&mut state_guard);

self.apply_entries(&mut state_guard);

}

fn advance_commit_index(&self, state_guard: &mut MutexGuard<'_, RaftNodeState<T>>) {

assert!(state_guard.status == RaftNodeStatus::Leader);

// find all match indexes that have quorum

let mut match_index_count: HashMap<u64, u64> = HashMap::new();

for &server_match_index in &state_guard.match_index {

*match_index_count.entry(server_match_index).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

let new_commit_index = match_index_count

.iter()

.filter(|(&match_index, &count)| {

count >= self.quorum_size().try_into().unwrap()

&& state_guard

.log

.get((match_index as usize).saturating_sub(1))

.map_or(false, |entry| entry.term == state_guard.current_term)

})

.map(|(&match_index, _)| match_index)

.max();

if let Some(max_index) = new_commit_index {

state_guard.commit_index = max_index;

}

}

If the append entry request fails, the leader checks to see if there is an earlier log entry that the follower might accept and retries the append entry request with that log entry.

Next, lets look at a follower node handling an append entries request from a leader.

fn handle_append_entries_request(

&mut self,

request: &AppendEntriesRequest<T>,

) -> AppendEntriesResponse {

let mut state_guard = self.state.lock().unwrap();

// the term check

if request.term < state_guard.current_term {

return AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

server_id: self.id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

success: false,

match_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

};

}

self.reset_election_timeout(&mut state_guard);

// log consistency check - check that the term and the index match at the log entry the leader expects

let log_index_to_check = request.prev_log_index.saturating_sub(1) as usize;

let prev_log_term = state_guard

.log

.get(log_index_to_check)

.map_or(0, |entry| entry.term);

let prev_log_index = state_guard

.log

.get(log_index_to_check)

.map_or(0, |entry| entry.index);

let log_ok = request.prev_log_index == 0

|| (request.prev_log_index > 0

&& request.prev_log_index <= state_guard.log.len() as u64

&& request.prev_log_term == prev_log_term);

// the log check is not OK, give false response

if !log_ok {

return AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

server_id: self.id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

success: false,

match_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

};

}

if request.entries.len() == 0 {

// this is a heartbeat message

state_guard.commit_index = request.leader_commit_index;

self.apply_entries(&mut state_guard);

return AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

server_id: self.id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

success: true,

match_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

};

}

// if there are any subsequent logs on the follower, truncate them and append the new logs

if self.len_as_u64(&state_guard.log) > request.prev_log_index {

state_guard.log.truncate(request.prev_log_index as usize);

state_guard.log.extend_from_slice(&request.entries);

if let Err(e) = self

.persistence_manager

.append_logs_at(&request.entries, request.prev_log_index.saturating_sub(1))

{

error!("There was a problem appending logs to stable storage for node {} at position {}: {}", self.id, request.prev_log_index - 1, e);

}

return AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

server_id: self.id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

success: true,

match_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

};

}

// There are no subsequent logs on the follower, so no possibility of conflicts. Which means the logs can just be appended

// and the response can be returned

state_guard.log.append(&mut request.entries.clone());

if let Err(e) = self.persistence_manager.append_logs(&request.entries) {

error!(

"There was a problem appending logs to stable storage for node {}: {}",

self.id, e

);

}

AppendEntriesResponse {

request_id: request.request_id,

server_id: self.id,

term: state_guard.current_term,

success: true,

match_index: state_guard.log.last().map_or(0, |entry| entry.index),

}

}

The follower first makes basic sanity checks - am i in a new epoch? No, okay continue. Does the log check pass? Okay, continue.

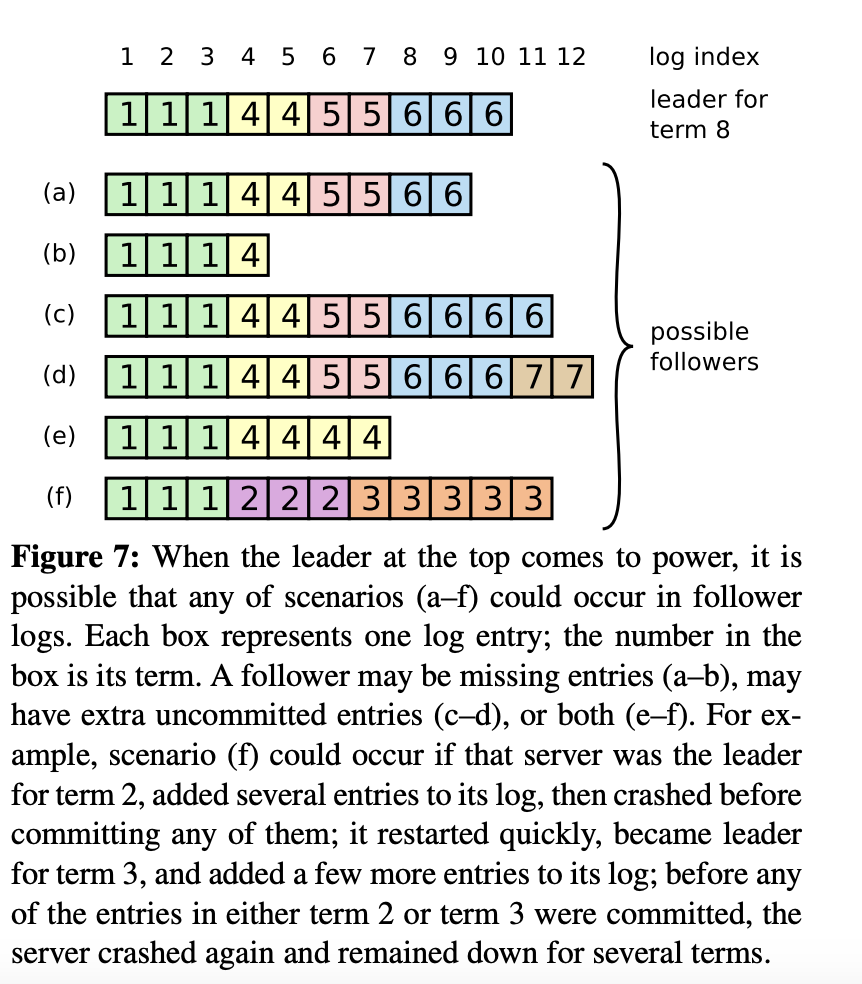

Once the basic sanity checks have passsed the leader then checks if it has any subsequent logs that the leader has not included in the request. This is tricky to grasp so look at the image below for a moment

The leader for term 8 has a max log index of 10 but it has followers which have a log index that is greater than its own maximum. So, what does the follower do in this case? The simple answer is that as long as the entries have not been committed to the state machine on the follower, they can be replaced which is exactly what the code does! It just removes everything past the point that is available in the leader’s request and replaces it with the leader’s entries. [Note: This is actually incorrect, because this could be an outdated RPC from the leader which might not contain the latest entries. But, that does not mean they should be removed. See Jon Gjengset’s guide to Raft here for more details].

Once all these checks have been taken care of, the follower is free to return a successful response. Once the follower returns a successful response, the logic above this section runs to check if the leader can update its own commit_index and apply entries to its state machine.

Persistence

This is probably the part of the implementation I did the most inefficient job on because I’m just not very used to working with file system semantics. Also, Rust being a new language to me probably didn’t help.

I hid the file system mechanics behind an API because I was sure that I’d be changing it in the future, which is why you’ll probably notice that its outside of the main.rs file. Here’s the interface I used for the file operations

pub trait RaftFileOps<T: Clone + FromStr + Display> {

fn read_term_and_voted_for(&self) -> Result<(Term, ServerId), io::Error>;

fn write_term_and_voted_for(

&self,

term: Term,

voted_for: Option<ServerId>,

) -> Result<(), io::Error>;

fn read_logs(&self, log_index: u64) -> Result<Vec<LogEntry<T>>, io::Error>;

fn append_logs(&mut self, entries: &Vec<LogEntry<T>>) -> Result<(), io::Error>;

fn append_logs_at(

&mut self,

entries: &Vec<LogEntry<T>>,

log_index: u64,

) -> Result<(), io::Error>;

}

pub struct DirectFileOpsWriter {

file_path: String,

file: RefCell<Option<File>>,

}

I use a RefCell for the DirectFileOpsWriter because I didn’t want to deal with Rust’s compiler complaining about multiple mutable borrows when I’m sure that a mutable borrow on these methods will not affect anything on the Raft node itself. I’m still not a 100% sure that this is the “correct” approach in Rust. Perhaps I need to re-design my structure itself to avoid using this pattern.

The format I chose to write was a CSV style format with separate lines for each entry. So, it looks something like this

1,2 <- This is the term and voted_for entries. The node voted in term 1 for node 2

1,1,0,1,1 <- The tuple shows (term,log_index,command,key,value)

The first line of the file can be repeatedly modified because for every term the node can either vote for itself or for another node. I suppose a different implementation could maintain a history of the node voted for in each term but the Raft spec does not make any assertions about the file format. Some educational implementations I see don’t even write or retrieve from storage. In fact, the Raft spec doesn’t include anything about storage, but of course you need to be able to write and retrieve from storage to make the implementation actually work otherwise how you would you recover from a crash?

Here’s some code around how the node restarts from stable storage.

fn restart(&mut self) {

let mut state_guard = self.state.lock().unwrap();

state_guard.status = RaftNodeStatus::Follower;

state_guard.next_index = vec![1; self.config.cluster_nodes.len()];

state_guard.match_index = vec![0; self.config.cluster_nodes.len()];

state_guard.commit_index = 0;

state_guard.votes_received = HashMap::new();

let (term, voted_for) = match self.persistence_manager.read_term_and_voted_for() {

Ok((t, v)) => (t, v),

Err(e) => {

panic!(

"There was an error while reading the term and voted for {}",

e

);

}

};

state_guard.current_term = term;

state_guard.voted_for = Some(voted_for);

let log_entries = match self.persistence_manager.read_logs(1) {

Ok(entries) => entries,

Err(e) => {

panic!("There was an error while reading the logs {}", e);

}

};

state_guard.log = log_entries;

}

Testing

Setting up a test rig to find bugs in this implementation was the most challenging part of writing the Raft implementation. I’m going to cover that in a separate post because that’s quite involved and it was more challenging to understand that then actually write the Raft implementation itself.

Future Work

There is a lot I want to do in my implementation still, not least changing the way I write to and retrieve from storage. Another few things that most people do in their implementations:

- Log snapshotting - instead of allowing the log to grow infinitely, keep taking a snapshot of the log and replacing the log up to the snapshot point

- Deterministic simulation testing - building a dead simple DST rig that I can run with more confidence to find more bugs. Creating scenario-based tests is quite time consuming. If you want to understand about DST, watch this video.

- Using custom network protocol - Just for fun

- Using custom binary format for storage to make it more efficient

- Using a better caching strategy for the file rather than re-opening it each time.

Credits

There’s quite a few useful posts and repos out there that helped me significantly while doing this implementation. Here are a few of those.

- Phil Eaton’s Raft implementation

- Jacky Zhao’s Raft implementation

- Jon Gjengset’s guide to Raft -> I only read it while writing this post and it already helped me uncover a bug

- The TLA+ spec of Raft by Diego Ongaro