Distributed Transactions With Percolator

This post covers a course that is part of TiDB’s talent plan on building a simple implementation of Percolator. You can find the course here

I stumbled upon the talent plan course by TiDB and decided to use it to understand distributed transactions (a.k.a Percolator) better.

The point of the Percolator course is to read the paper and implement it in Rust, so I’ll be diving into bits and pieces of the paper as well.

Overview

Percolator came out of Google in 2010 as a way to run distributed transactions on top of Bigtable, Google’s distributed storage system. At the time Google wanted to run transactions on a regular DBMS but nothing came close to handling the volume Google had, so they built a distributed transaction model on top of their own distributed data source.

Mechanics

The mechanics of Percolator are deceptively simple. It’s a straightforward algorithm to understand, albeit with a lot of bookkeeping involved. Let’s look at how it would work for a simple key-value store.

Every key has 3 columns attached to it - a Data column, a Lock column and a Write column. Every transaction commit has 2 phases - a pre-write phase and a commit phase.

The pre-write phase involves writing to the Data & Lock columns - that is, whatever the new value the transaction wants to write and an associated lock. Now, the transaction hasn’t committed yet, so this newly written value is not visible yet.

The transaction commit phase involves some validation checks and assuming those validation checks pass, the lock is removed and a pointer to the Data column is placed in the Write column.

Let’s run through an example transaction. (Look here for a detailed example from TiKV).

I’ll work through an example that uses markers more pertinent to the codebase for the course. The examples provided in the paper and the blog post from TiKV use slightly different markers in the rows, but they’re functionally the same.

Initial State

Let’s say we start out with a simple key value store that represents the accounts of individuals. There are 2 account holders Bob and Joe with an initial balance of 10$ and 2$ respectively. We will run a transaction that will transfer 7$ from Bob to Joe.

The image below shows the initial state we will start from.

The key is a tuple representing the (key, timestamp) of the transaction that wrote that data into it. The value can either be a set of bytes representing the data or a timestamp serving as a pointer (The value can also have a third variant, which is wall clock timestamp. I’ll get to that next). The write column has a pointer pointing to the timestamp in the data column where the data actually resides as a value.

You’ll notice that the timestamps in the data column and the write column are different because they represent the start and commit timestamps of the transaction that wrote this data and committed it. An invariant that must always be held is that commit timestamp > start timestamp. This is ensured by a timestamp oracle, which is a fancy term for a server that hands out strictly monotonically increasing values. The strictly is doing a lot of work here because it means that you are guaranteed to never see a timestamp more than once.

Pre-Write

Now, let’s say the transaction begins that will transfer the amount of 7$ from Bob to Joe. This transaction will begin with a timestamp of t2. The first thing this transaction does it to acquire a lock on both keys that are involved in the transaction, and write down the data that should be the end result of this transaction.

The entries in the two columns are different - one of them is selected as the primary lock (the key with a # symbol) and the other (or others, depending on the number of keys involved in the transaction) are selected as secondaries. The primary lock is primarily used as a synchronization point in case of any cleanup required. This cleanup is usually done if a transaction has crashed or failed to remove all of it’s locks.

Commit

As part of the commit phase, the transaction will perform some validation checks (this is implementation dependent but the main check is that the primary lock hasn’t been removed). Assuming these validation checks pass, the transaction will erase the locks placed on all the rows and place a new entry in the write column serving as a pointer to the entry in the data column that was created in the pre-commit phase. It marks the new entry in the write column with a commit timestamp.

Implementation

Let’s dive into an implementation of the Percolator algorithm. The base for this was taken from the TiKV course. If you just want to jump straight to my full implementation, go here.

The course gives you a client and server implementation with the functionality stubbed out. The goal is for you to write that functionality. Very helpfully, the course gives you a network implementation between the client and the server which simulates faults like dropped requests which help you test your implementation. (testing distributed systems is more than half the problem).

Write Path

Let’s cover the write path first. A transaction client write’s all data into a private buffer until it is time to actually perform the commit.

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct Client {

// Your definitions here.

tso_client: TSOClient,

txn_client: TransactionClient,

transaction: Option<Transaction>,

}

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct KVPair {

key: Vec<u8>,

value: Vec<u8>,

}

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct Transaction {

pub start_ts: u64,

pub write_buffer: Vec<KVPair>,

}

impl Transaction {

pub fn new(start_ts: u64) -> Self {

Transaction {

start_ts,

write_buffer: Vec::new(),

}

}

}

impl Client {

/// Creates a new Client.

pub fn new(tso_client: TSOClient, txn_client: TransactionClient) -> Client {

// Your code here.

Client {

tso_client,

txn_client,

transaction: None,

}

}

/// Gets a timestamp from a TSO.

pub fn get_timestamp(&self) -> Result<u64> {

let rpc = || self.tso_client.get_timestamp(&TimestampRequest {});

match executor::block_on(self.call_with_retry(rpc)) {

Ok(ts) => Ok(ts.timestamp),

Err(e) => Err(e),

}

}

/// Begins a new transaction.

pub fn begin(&mut self) {

let ts = self

.get_timestamp()

.expect("unable to get a timestamp from the oracle");

let transaction = Transaction::new(ts);

self.transaction = Some(transaction);

}

/// Sets keys in a buffer until commit time.

pub fn set(&mut self, key: Vec<u8>, value: Vec<u8>) {

// Your code here.

if let Some(transaction) = self.transaction.as_mut() {

transaction.write_buffer.push(KVPair { key, value });

return;

}

panic!("attempting to set a key value pair without a txn");

}

}

Now, when the transaction performs the commit it runs through the two phases - pre-write and commit per key-value pair on the client.

/// Commits a transaction.

pub fn commit(&self) -> Result<bool> {

// PRE-WRITE PHASE

let transaction = self.transaction.as_ref().expect("transaction not found");

let kv_pair = &transaction.write_buffer;

let primary = kv_pair

.first()

.expect("cannot find the first key value pair");

let secondaries = &kv_pair[1..];

// acquire a lock on the primary first

let args = PrewriteRequest {

timestamp: transaction.start_ts,

kv_pair: Some(KvPair {

key: primary.key.clone(),

value: primary.value.clone(),

}),

primary: Some(KvPair {

key: primary.key.clone(),

value: primary.value.clone(),

}),

};

let rpc = || self.txn_client.prewrite(&args);

if executor::block_on(self.call_with_retry(rpc))?.res == false {

return Ok(false);

}

// acquire locks on the secondaries now

for kv_pair in secondaries {

let args = PrewriteRequest {

timestamp: transaction.start_ts,

kv_pair: Some(KvPair {

key: kv_pair.key.clone(),

value: kv_pair.value.clone(),

}),

primary: Some(KvPair {

key: primary.key.clone(),

value: primary.value.clone(),

}),

};

let rpc = || self.txn_client.prewrite(&args);

if executor::block_on(self.call_with_retry(rpc))?.res == false {

return Ok(false);

}

}

// END PRE-WRITE PHASE

// COMMIT PHASE

let commit_ts = self.get_timestamp()?;

assert!(

commit_ts > transaction.start_ts,

"panic because the commit ts is not strictly greater than the start ts of the txn"

);

let args = CommitRequest {

start_ts: transaction.start_ts,

commit_ts,

is_primary: true,

kv_pair: Some(KvPair {

key: primary.key.clone(),

value: primary.value.clone(),

}),

};

let rpc = || self.txn_client.commit(&args);

match executor::block_on(self.call_with_retry(rpc)) {

Ok(response) => {

return Ok(response.res);

}

Err(e) => match e {

labrpc::Error::Other(e_string) if e_string == "reqhook" => {

return Ok(false);

}

_ => return Err(e),

},

}

for kv_pair in secondaries {

let args = CommitRequest {

start_ts: transaction.start_ts,

commit_ts,

is_primary: false,

kv_pair: Some(KvPair {

key: primary.key.clone(),

value: primary.value.clone(),

}),

};

let rpc = || self.txn_client.commit(&args);

match executor::block_on(self.call_with_retry(rpc)) {

Ok(response) => return Ok(response.res),

Err(e) => match e {

labrpc::Error::Other(e_string) => {

if e_string == "reqhook" {

return Ok(true);

}

}

_ => return Err(e),

},

}

}

// END COMMIT PHASE

Ok(true)

}

There’s a bunch of additional code ensuring that the RPC call is retried x number of times, but the gist is the same as that of the paper.

Now, for the server side, we have 3 main components - a memory storage server, a key value table and the timestamp oracle. The key value table holds the actual data and the memory storage server manages the business logic of the transaction.

// KvTable is used to simulate Google's Bigtable.

// It provides three columns: Write, Data, and Lock.

#[derive(Clone, Default)]

pub struct KvTable {

write: BTreeMap<Key, Value>,

data: BTreeMap<Key, Value>,

lock: BTreeMap<Key, Value>,

}

impl KvTable {

// Reads the latest key-value record from a specified column

// in MemoryStorage with a given key and a timestamp range.

#[inline]

fn read(

&self,

key: Vec<u8>,

column: Column,

ts_start_inclusive: Option<u64>,

ts_end_inclusive: Option<u64>,

) -> Option<(Key, Value)> {

let col = match column {

Column::Data => &self.data,

Column::Lock => &self.lock,

Column::Write => &self.write,

};

let mut res = None;

let mut max_timestamp_seen = 0;

for ((k, ts), value) in col.iter() {

if k == &key

&& ts_start_inclusive.map_or(true, |start| *ts >= start)

&& ts_end_inclusive.map_or(true, |end| *ts <= end)

&& *ts >= max_timestamp_seen

{

max_timestamp_seen = *ts;

res = Some(((k.clone(), *ts), value.clone()));

}

}

res

}

// Writes a record to a specified column in MemoryStorage.

#[inline]

fn write(&mut self, key: Vec<u8>, column: Column, ts: u64, value: Value) {

let col = match column {

Column::Data => &mut self.data,

Column::Lock => &mut self.lock,

Column::Write => &mut self.write,

};

col.insert((key, ts), value);

}

#[inline]

// Erases a record from a specified column in MemoryStorage.

fn erase(&mut self, key: Vec<u8>, column: Column, commit_ts: u64) {

let col = match column {

Column::Data => &mut self.data,

Column::Lock => &mut self.lock,

Column::Write => &mut self.write,

};

let mut keys_to_remove = Vec::new();

for ((k, ts), _) in col.iter() {

if k == &key && *ts == commit_ts {

keys_to_remove.push((k.clone(), *ts));

}

}

for key in keys_to_remove {

let value = col.remove(&key);

assert!(value.is_some());

}

}

}

// MemoryStorage is used to wrap a KvTable.

// You may need to get a snapshot from it.

#[derive(Clone, Default)]

pub struct MemoryStorage {

data: Arc<Mutex<KvTable>>,

}

#[async_trait::async_trait]

impl transaction::Service for MemoryStorage {

// example prewrite RPC handler.

async fn prewrite(&self, req: PrewriteRequest) -> labrpc::Result<PrewriteResponse> {

let primary = req.primary.ok_or_else(|| {

labrpc::Error::Other("primary kv_pair is missing in the prewrite request".to_string())

})?;

let kv_pair = req.kv_pair.ok_or_else(|| {

labrpc::Error::Other("kv_pair is missing in the prewrite request".to_string())

})?;

let mut storage = self.data.lock().unwrap();

match storage.read(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Write,

Some(req.timestamp),

None,

) {

Some(_) => return Ok(PrewriteResponse { res: false }),

None => (),

};

match storage.read(kv_pair.key.clone(), Column::Lock, Some(0), None) {

Some(_) => return Ok(PrewriteResponse { res: false }),

None => (),

};

// all checks completed, place data and lock

storage.write(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Data,

req.timestamp,

Value::Vector(kv_pair.value.clone()),

);

if primary == kv_pair {

storage.write(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Lock,

req.timestamp,

Value::LockPlacedAt(SystemTime::now()),

);

} else {

storage.write(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Lock,

req.timestamp,

Value::Vector(primary.key),

);

}

Ok(PrewriteResponse { res: true })

}

// example commit RPC handler.

async fn commit(&self, req: CommitRequest) -> labrpc::Result<CommitResponse> {

let mut storage = self.data.lock().unwrap();

let kv_pair = req

.kv_pair

.expect("kv_pair is missing in the commit request");

if req.is_primary {

// check lock on primary still holds

match storage.read(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Lock,

Some(req.start_ts),

Some(req.start_ts),

) {

Some(_) => (),

None => {

return Ok(CommitResponse { res: false });

}

};

}

// create write and remove lock

storage.write(

kv_pair.key.clone(),

Column::Write,

req.commit_ts,

Value::Timestamp(req.start_ts),

);

storage.erase(kv_pair.key, Column::Lock, req.start_ts);

Ok(CommitResponse { res: true })

}

}

While doing the prewrite phase, you’ll notice that there is a check to determine what the primary lock is supposed to be. The value written into the primary lock is the wall clock time when it is being placed. This is important during the read path.

The commit handler is a lot simpler - the only validation it does is to determine that if the primary is being committed that the lock is still valid. It doesn’t need to do that for the secondaries.

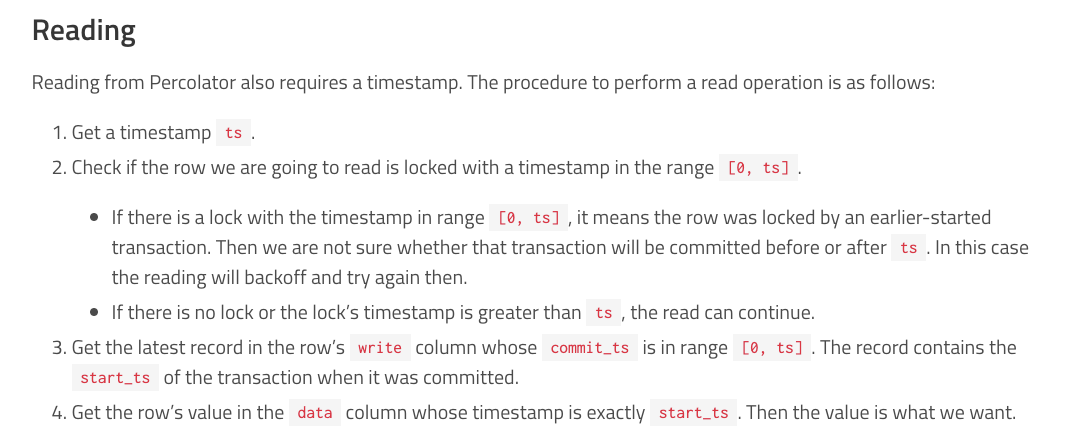

Read Path

Let’s deal with a straightforward read path first - one where it doesn’t encounter any locks. This post from TiKV has a great explanation of the read path, so I’m going to use the text from there as an explanation.

The basic idea is that you first check if there are any pending locks. Assuming there are none, fetch the latest write record within range and use the pointer there to the data column to get the actual value.

#[async_trait::async_trait]

impl transaction::Service for MemoryStorage {

// example get RPC handler.

async fn get(&self, req: GetRequest) -> labrpc::Result<GetResponse> {

loop {

let mut storage = self.data.lock().unwrap();

let is_row_locked =

storage.read(req.key.clone(), Column::Lock, Some(0), Some(req.timestamp));

if is_row_locked.is_some() {

drop(storage);

self.back_off_maybe_clean_up_lock(req.timestamp, req.key.clone());

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(100));

continue;

}

let start_ts =

match storage.read(req.key.clone(), Column::Write, Some(0), Some(req.timestamp)) {

Some(((_, commit_ts), value)) => match value {

Value::Timestamp(start_ts) => start_ts,

_ => {

return Err(labrpc::Error::Other(format!(

"unexpected value found in write column for key {:?} at ts {}",

req.key, commit_ts

)))

}

},

None => {

return Ok(GetResponse {

success: false,

value: Vec::new(),

});

}

};

let data = match storage.read(

req.key.clone(),

Column::Data,

Some(start_ts),

Some(start_ts),

) {

Some(((_, _), value)) => match value {

Value::Vector(bytes) => bytes,

_ => {

return Err(labrpc::Error::Other(format!(

"unexpected value found in data column for key {:?} at ts {}",

req.key, start_ts

)));

}

},

None => {

return Err(labrpc::Error::Other(format!(

"No value found in data column for key {:?} at timestamp {}",

req.key, start_ts

)));

}

};

return Ok(GetResponse {

success: true,

value: data,

});

}

}

}

The code is verbose because of all the match guards but hopefully straighforward to follow. (On another note, I find myself writing very verbose Rust code which is what the language seems to lend itself to.)

Now, let’s dive into dealing with pending locks and potentially failed transactions on the read path. First, let’s look at what the paper says about dealing with these transactions.

.......

.......

.......

When a client crashes during the second phase of commit, a transaction will be past the commit point (it has written at least one write record) but will still 5 have locks outstanding. We must perform roll-forward on these transactions. A transaction that encounters a lock can distinguish between the two cases by inspecting the primary lock: if the primary lock has been replaced by a write record, the transaction which wrote the lock must have committed and the lock must be rolled forward, otherwise it should be rolled back (since we always commit the primary first, we can be sure that it is safe to roll back if the primary is not committed). To roll forward, the transaction performing the cleanup replaces the stranded lock with a write record as the original transaction would have done.So Percolator distinguishes between crashes by determining when a client has crashed.

-

If it crashes after the pre-commit phase but before the commit phase, the transaction must be rolled back. The way to determine this is to check if the

TTLon the wall clock time for the primary lock has elapsed. -

If the client crashed after committing the primary lock in the commit phase but before committing the secondary locks, the transaction must be rolled forward since the only synchronization point is the primary lock itself.

Here’s all the code related to that. It’s slightly complicated by the fact that a get request might come across a secondary lock, in which case it needs handle the indirection. I’ve tried to document this function as clearly as possible so it’s easier to follow.

impl MemoryStorage {

fn back_off_maybe_clean_up_lock(&self, start_ts: u64, key: Vec<u8>) {

// STEPS:

// 1. Recheck the condition that prompted this call by re-acquiring lock. Things might have changed

// 2. Check if the lock is the primary lock. If secondary lock, get primary lock

// 3. If primary lock present and

// a. has expired, roll-back the txn

// b. has not expired, do nothing and retry after some time

// 4. If primary lock not present and

// a. Data found in Write column, roll-forward the txn

// b. No data found in Write column, remove stale lock

let mut storage = self.data.lock().unwrap();

let ((key, start_ts), value) =

match storage.read(key.clone(), Column::Lock, Some(0), Some(start_ts)) {

Some((key, value)) => (key, value),

None => return,

};

let is_primary_lock = match value {

Value::LockPlacedAt(creation_time) => true,

Value::Vector(ref data) => false,

Value::Timestamp(_) => panic!(

"unexpected value of bytes found in lock column, expected SystemTime or Vec<u8>"

),

};

if is_primary_lock {

if self.check_if_primary_lock_expired(value) {

self.remove_lock_and_rollback(&mut storage, key, start_ts);

}

return;

}

// handle the secondary lock here

let primary_key = value

.as_vector()

.expect("unexpected value in lock column, expected Vec<u8>");

match storage.read(primary_key.clone(), Column::Lock, Some(0), Some(start_ts)) {

Some(((_, conflicting_start_ts), value)) => {

if self.check_if_primary_lock_expired(value) {

self.remove_lock_and_rollback(&mut storage, primary_key, conflicting_start_ts);

self.remove_lock_and_rollback(&mut storage, key, start_ts);

return;

}

}

None => {

// the primary lock is gone, check for data

match storage.read(primary_key, Column::Write, None, None) {

None => {

self.remove_lock_and_rollback(&mut storage, key, start_ts);

}

Some(((_, commit_ts), value)) => {

let start_ts = value

.as_timestamp()

.expect("unexpected value in write column, expected ts");

self.remove_lock_and_roll_forward(&mut storage, key, start_ts, commit_ts);

}

}

}

}

}

fn check_if_primary_lock_expired(&self, value: Value) -> bool {

let lock_creation_time = value

.as_lock_placed_at()

.expect("unexpected value in lock column, expected SystemTime");

let ttl_duration = Duration::from_nanos(TTL);

let future_time = lock_creation_time + ttl_duration;

future_time < SystemTime::now()

}

fn remove_lock_and_rollback(

&self,

storage: &mut std::sync::MutexGuard<KvTable>,

key: Vec<u8>,

timestamp: u64,

) {

storage.erase(key.clone(), Column::Lock, timestamp);

storage.erase(key.clone(), Column::Data, timestamp);

}

fn remove_lock_and_roll_forward(

&self,

storage: &mut std::sync::MutexGuard<KvTable>,

key: Vec<u8>,

start_ts: u64,

commit_ts: u64,

) {

storage.erase(key.clone(), Column::Lock, start_ts);

storage.write(key, Column::Write, commit_ts, Value::Timestamp(start_ts));

}

}

Aside

As an aside, something that bothered me while doing this course was that failed transactions are only cleaned up on the read path. What happens if we have a set of transactions that do only writes with no reads and they all keep failing? Theoretically, we could have an entire database locked up that would require a read request to come in and start freeing up locked rows.

I’m basing all this on the pseudo-code that the paper presents, part of which I have included below.

1 class Transaction {

2 struct Write { Row row; Column col; string value; };

3 vector<Write> writes ;

4 int start ts ;

5

6 Transaction() : start ts (oracle.GetTimestamp()) {}

7 void Set(Write w) { writes .push back(w); }

8 bool Get(Row row, Column c, string* value) {

9 while (true) {

10 bigtable::Txn T = bigtable::StartRowTransaction(row);

11 // Check for locks that signal concurrent writes.

12 if (T.Read(row, c+"lock", [0, start ts ])) {

13 // There is a pending lock; try to clean it and wait

14 BackoffAndMaybeCleanupLock(row, c);

15 continue;

16 }

Figure 6: Pseudocode for Percolator transaction protocol.

I still don’t have a satisfactory answer to this question. I imagine different implementations of Percolator include cleanup logic on the write path as well.