How The Internet Speaks

A Story Of Communication

Have you ever wondered how the internet actually speaks? How does one computer “talk” to another computer over the internet?

When people communicate with one another, we use words strung into seemingly meaningful sentences. The sentences only make sense because we’ve agreed on a meaning for these sentences. We’ve defined a protocol of communication, so to speak.

Turns out, computers speak to each other in a similar fashion over the internet. But, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. People use their mouths to communicate, let’s figure out what the mouth of the computer is first.

Enter The Socket

The socket is one of the most fundamental concepts in computer science. You can build entire networks of inter-connected devices using sockets.

Like all other things in computer science, a socket is a very abstract concept. So, rather than define what a socket is, it is far easier to define what a socket does.

So, what does a socket do? It helps two computers communicate with each other. How does it do this? It has two methods defined, called send() and recv()

Okay, that’s all great, but what do send() and recv() send and receive? When people move their mouths, they exchange words. When sockets use their methods, they exchange bits and bytes.

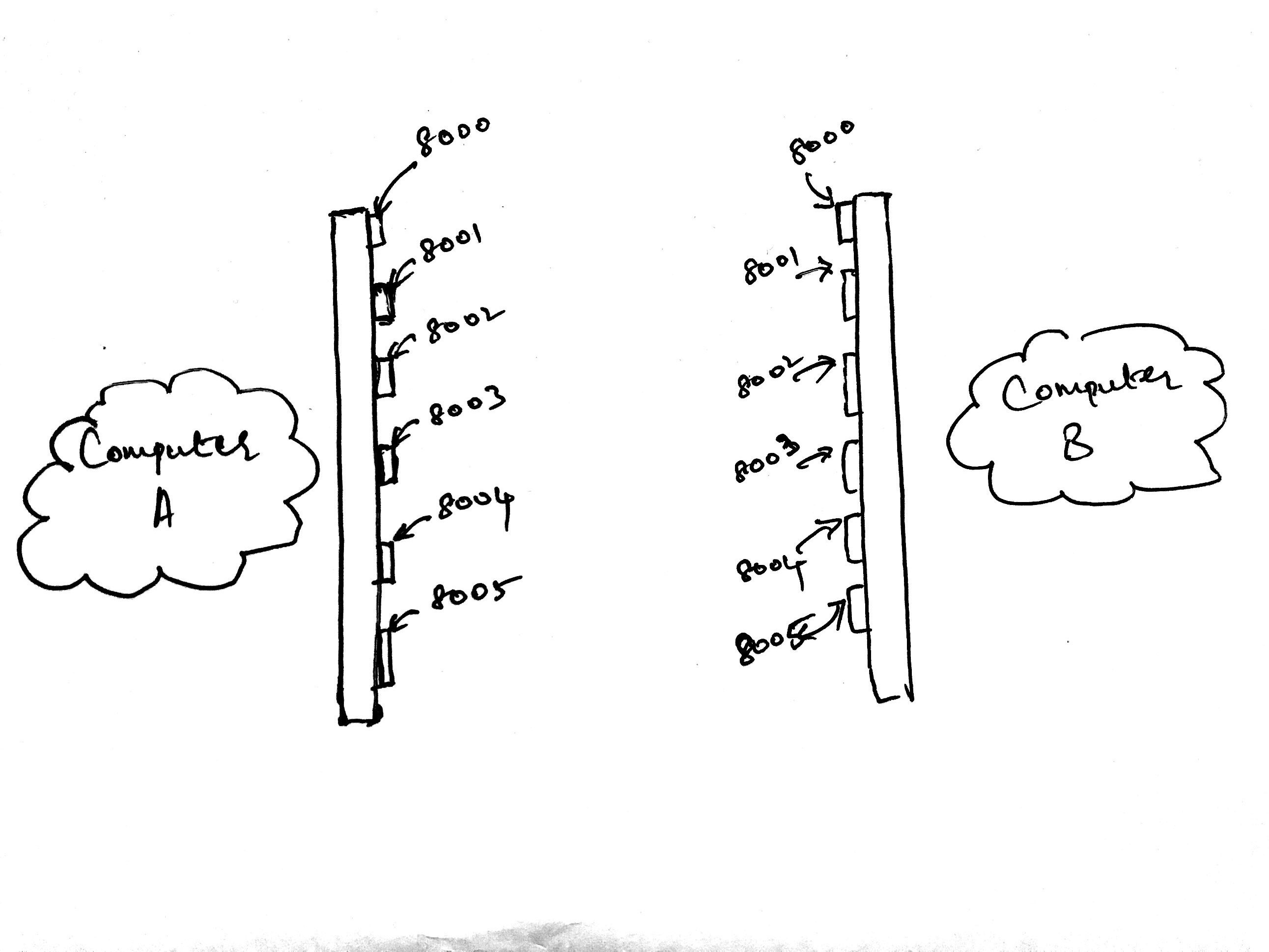

Lets illustrate the methods with an example. Let’s say we have two computers, A and B. Computer A is trying to say something to Computer B. Therefore, Computer B is trying to listen to what Computer A is saying. Here’s what that would look like.

Reading The Buffer

Looks a little odd, doesn’t it? For one, both computers are pointing to a bar in the middle, entitled ‘buffer’.

What is the buffer? The buffer is a memory stack. It’s where the data for each computer is stored, and is allocated by the kernel.

Next, why are they both pointing to the same buffer? Well, that’s not quite accurate actually. Each computer has it’s own buffer allocated by its own kernel and the network transports the data between the two separate buffers. But, I don’t want to get into network details here, so we’ll assume that both computers have access to the same buffer placed “somewhere in the void between”.

Okay, now that we know what this looks like visually, let’s abstract it away into code.

#Computer A sends data

computerA.send(data)

#Computer B receives data

computerB.recv(1024)

This code snippet does the exact same thing the image above represents. Except for one curiosity, we don’t say computerB.recv(data). Instead, we specify a seemingly random number in the place of data

The reason is simple. Data over a network is transmitted in bits. Therefore, when we recv in computerB, we specify the number of bits we are willing to receive at any one given point in time.

Why did I pick 1024 bytes to receive at once? No specific reason. It is usually best to specify the number of bytes you would receive in a power of 2. I picked 1024 which is 2^10.

So, how does the buffer figure into this? Well, Computer A writes or sends whatever is stored in data into the buffer. Computer B decides to read or receive the first 1024 bytes of what is stored in that buffer.

Okay, awesome! But, how do these two computers know to talk to each other? For instance, when Computer A writes to this buffer, how does it know that Computer B is going to pick it up? To rephrase that, how can ensure that a connection between two computers has a unique buffer?

Porting Into IPs

The image above shows the same two computers we’ve been working on all along with one more detail added in. There are a bunch of numbers listed in front of each computer along the length of a bar.

Consider the long bar in front of each computer to be the router that connects a specific computer to the internet. Those numbers listed on each bar are called ports. Your computer has thousands of ports available on it right now. Each port allows a socket connection. I’ve only shown 6 ports in the image above, but you get the idea.

Ports below 255 are generally reserved for system calls and low-level connections. It is generally advisable to open up a connection on a port in the high 4-digits, like 8000. I haven’t drawn the buffer in the image above, but you can assume that each port has its own buffer.

The bar itself also has a number associated with it. This number is called the IP address. The IP address has a bunch of ports associated with it. Think of it in the following way

127.0.0.1

/ | \

/ | \

/ | \

8000 8001 8002

Great, let’s set up a connection on a specific port between Computer A and Computer B.

# computerA.py

import socket

computerA = socket.socket()

# Connecting to localhost:8000

computerA.connect(('127.0.0.1', 8000))

string = 'abcd'

encoded_string = string.encode('utf-8')

computerA.send(encoded_string)

# computerB.py

import socket

computerB = socket.socket()

# Listening on localhost:8000

computerB.bind(('127.0.0.1', 8000))

computerB.listen(1)

client_socket, address = computerB.accept()

data = client_socket.recv(2048)

print(data.decode('utf-8'))

It looks like we’ve jumped a little ahead in terms of the code, but I’ll step through it. We know we have two computers, A and B. Therefore, we need one to send data and one to receive data.

I have arbitrarily selected A to send data and B to receive data. In this line computerA.connect((‘127.0.0.1’, 8000) I am making computerA connect to port 8000 on IP address 127.0.0.1.

Note: 127.0.0.1 typically means localhost, which references your machine

Then, for computerB, I am making it bind to port 8000 on IP address 127.0.0.1. Now, you’re proabbly wondering why I have the same IP address for two different computers. That’s because I’m cheating. I’m using one computer to demonstrate how you can use sockets. Typically two different computers would have two different IP addresses.

We already know that only bits can be sent as part of a data packet, which is why we encode the string before sending it over. Similarly, we decode the string on Computer B. If you decide to run the above two files locally, make sure to run computerB.py file first. If you run the computerA.py file first, you will get a connection refused error.

Serving The Clients

I’m sure its been fairly obvious to many of you that what I’ve been describing so far is a very simplistic client-server model. In fact you can see that from the above image, all I’ve done is replace Computer A as the client and Computer B as the server.

There is a constant stream of communication that goes on between clients and servers. In our prior code example, we described a one shot of data transfer. Instead, what we want is a constant stream of data being sent from the client to the server. However, we also want to know when that data transfer is complete, so we know we can stop listening.

Let’s try to use an analogy to examine this further. Imagine the following conversation between two people.

Two people are trying to introduce themselves. However, they will not try to talk at the same time. Let’s assume that Raj goes first. John will then wait until Raj has finished introducing himself before he begins introducing himself. This is based on some learned heuristics but we can generally describe the above as a protocol.

Our clients and servers need a similar protocol. Or else, how would they know when it’s their turn to send packets of data.

We’ll do something simple to illustrate this. Let’s say we want to send some data which happens to be an array of strings. Let’s assume the array is as follows

arr = ['random', 'strings', 'that', 'need', 'to', 'be', 'transferred', 'across', 'the', 'network', 'using', 'sockets']

The above is the data that is going to be written from the client to the server. Let’s create another constraint. The server needs to accept data that is exactly equivalent to the data occupied by the string that is going to be sent across at that instant.

So, for instance, if the client is going to send across the string ‘random’, and let’s assume each character occupies 1 byte, then the string itself occupies 6 bytes. 6 bytes is then equal to 6*8 = 48 bits. Therefore, for the string ‘random’ to be transferred across sockets from the client to the server, the server needs to know that it has to access 48 bits for that specific packet of data.

This is a good opportunity to break the problem down. There are a couple of things we need to figure out first.

- How do we figure out the number of bytes a string occupies in Python?

Well, we could start by figuring out the length of a string first. That’s easy, it’s just a call to len(). But, we still need to know the number of bytes occupied by a string, not just the length.

We’ll convert the string to binary first, and then find the length of the resulting binary representation. That should give us the number of bytes used. len(‘random’.encode(‘utf-8’)) will give us what we want

- How do we send the number of bytes occupied by each string to the server?

Easy, we’ll convert the number of bytes (which is an integer) into a binary representation of that number, and send it to the server. Now, the server can expect to receive the length of a string before receiving the string itself.

- How does the server know when the client has finished sending all the strings?

Remember from the analogy of the conversation, there needs to be a way to know if the data transfer has completed. Computers don’t have their own heuristics they can rely on. So, we’ll provide a random rule. We’ll say that when we send across the string ‘end’, that means the server has received all the strings and can now close the connection. Obviously, this means that we can’t use the string ‘end’ in any other part of our array except the very end.

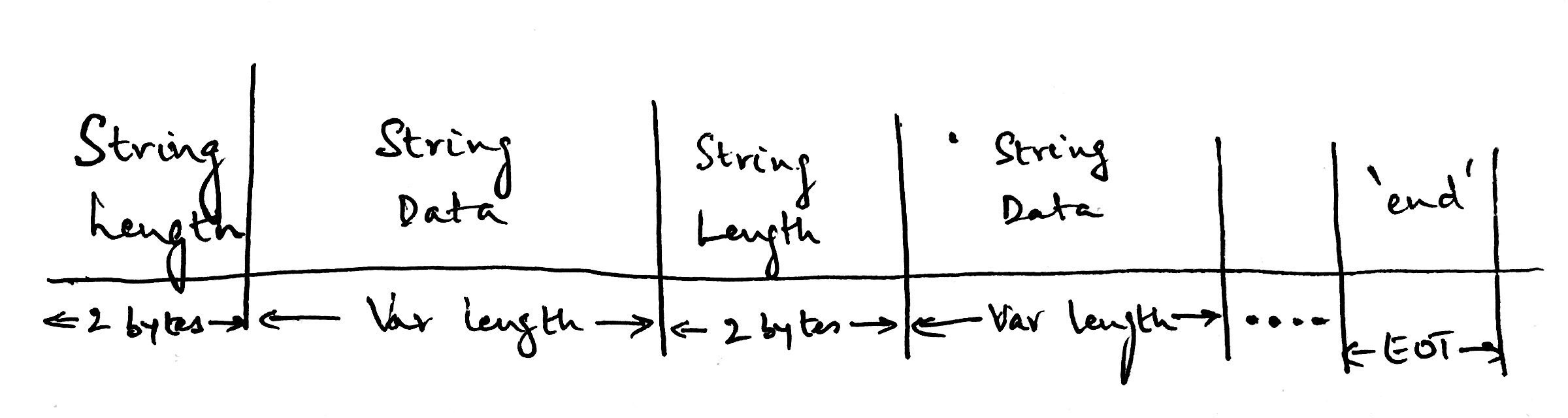

Here’s the protocol we’ve designed so far:

The length of the string will be 2 bytes, followed by the actual string itself which will be variable length. It will depend on the string length sent in the previous packet, and we will alternate between sending the string lengths and the string itself. The EOT stands for End Of Transmission, and sending the string ‘end’ means that there is no more data to send.

Note: Before we continue, I want to point out the obvious. This is a very simple and stupid protocol. If you want to see what a well-designed protocol looks like, look no further than the HTTP protocol.

Let’s code this out. I’ve included comments in the code below so it’s self-explanatory.

Great, we have a client running. Next, we need the server.

I want to explain a few specific lines of code in the above gists. The first, from the clientSocket.py file

len_in_bytes = (len_of_string).to_bytes(2, byteorder='little')

What the above does is convert a number into bytes. The first parameter passed to the to_bytes function is the number of bytes allocated to the result of converting len_of_string to its binary representation.

The second parameter is used to decide whether to follow the Little Endian format or the Big Endian format. You can read more about it here. For now, just know that we will always stick with little for that parameter.

The next line of code I want to take a look at is client_socket.send(string.encode(‘utf-8’)). We’re converting the string to a binary format using the ‘utf-8’ encoding.

Next, in the serverSocket.py file:

data = client_socket.recv(2)

str_length = int.from_bytes(data, byteorder='little')

The first line of code above receives 2 bytes of data from the client. Remember that when we converted the length of the string to a binary format in clientSocket.py, we decided to store the result in 2 bytes. This is why we’re reading 2 bytes here for that same data.

Next line involves converting the binary format to an integer. The byteorder here is “little”, to match the byteorder we used on the client.

If you go ahead and run the two sockets, you should see that the server will print out the strings the client sends across. We established communication!

Conclusion

Okay, we covered quite a bit so far. Namely, what are sockets, how we use them and how to design a very simple and stupid protocol. If you want to learn more about how sockets work, I highly recommend reading Beej’s Guide To Network Programming. That book has a lot of great stuff in it.

You can of course take what read in this article so far, and apply it to more complex problems like streaming images from a camera to your computer.

If you want to follow me on Twitter or GitHub, you can do so (here)[https://twitter.com/zz_humayun] and (here)[https://github.com/redixhumayun]. I’m always available if you want to reach out to me!