Manufacturing On The Internet

Hold On, What?

Yup, weighty title. Definitely a little clickbaity. But, I want to attract attention to this.

So, let me try and explain exactly what I’m trying to do and why I think its important.

In a previous post, I described why communication is the most important problem any organization can solve. Now, I’m going to apply that to the world of garment manufacturing and explain what I’m trying to build.

This post is a way for me to lay my thoughts out in order and a marketing tool to attract people to help build this.

Where Is Garment Manufacturing Today?

Garment manufacturing is almost entirely secluded from the internet, and that’s a big deal. In fact, manufacturing for the most part is secluded from the internet.

For instance, imagine that you wanted to buy a t-shirt from an online store. You log onto Myntra, search through all of the available options and you pick something you like that you think:

- Fits you reasonably well

- Meets your budget

- Is from a brand that you find desirable

So, you pick the t-shirt you like, you go through checkout, pay for the t-shirt (along the way Myntra tries to get you to buy some other stuff) and Myntra sends you a confirmation email. In the email they tell you by when you can expect the order.

When Myntra ships the order they send you a message notifying you and allow you to live track your delivery. When you accept your delivery, you get another message.

The one thing Myntra has done throughout with you is clear and succinct communication.

They told you when you would receive the order, when your order was shipped and sent you a notification indicating that you received it. Now, you trust Myntra.

Communication breeds trust

In the post I linked to above, I said that every problem is a communication problem. I want to expand on that. Every problem is a problem of communication & trust. And communication breeds trust.

Now, let’s leave behind the relationship between you & Myntra and jump to the relationship between Myntra & the manufacturer of the t-shirt you just bought.

How Was The T-Shirt Made?

So, how did that t-shirt get manufactured?

-

Myntra had their designers come up with styles based on current trends

-

Myntra provided these designs to their suppliers so the manufacturers could create samples

-

Myntra picked one manufacturer based on their preferences

In fact, the t-shirt you’re seeing on Myntra today was probably styled and manufactured months ago.

When a manufacturer receives an order, it is usually for a quantity of lakhs of pieces. The order also comes in a cut-to-pack ratio, which is just a fancy term for the ratio of sizes in which the buyer wants their goods shipped out.

Here’s one example of what a sample order might look like. The country associated with each row is the destination port for a carton containing the corresponding number of garments per size.

Country S M L XL

USA 100 100 400 200

Russia 100 100 250 50

China 300 300 100 0

So, what needs to happen now? It’s actually relatively straightforward.

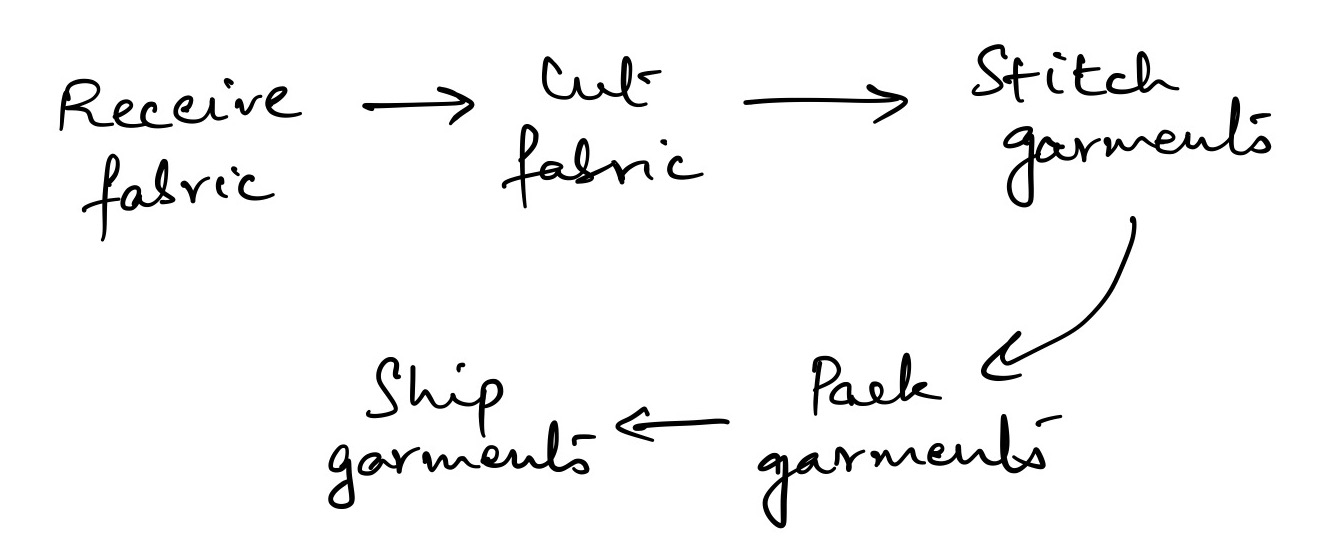

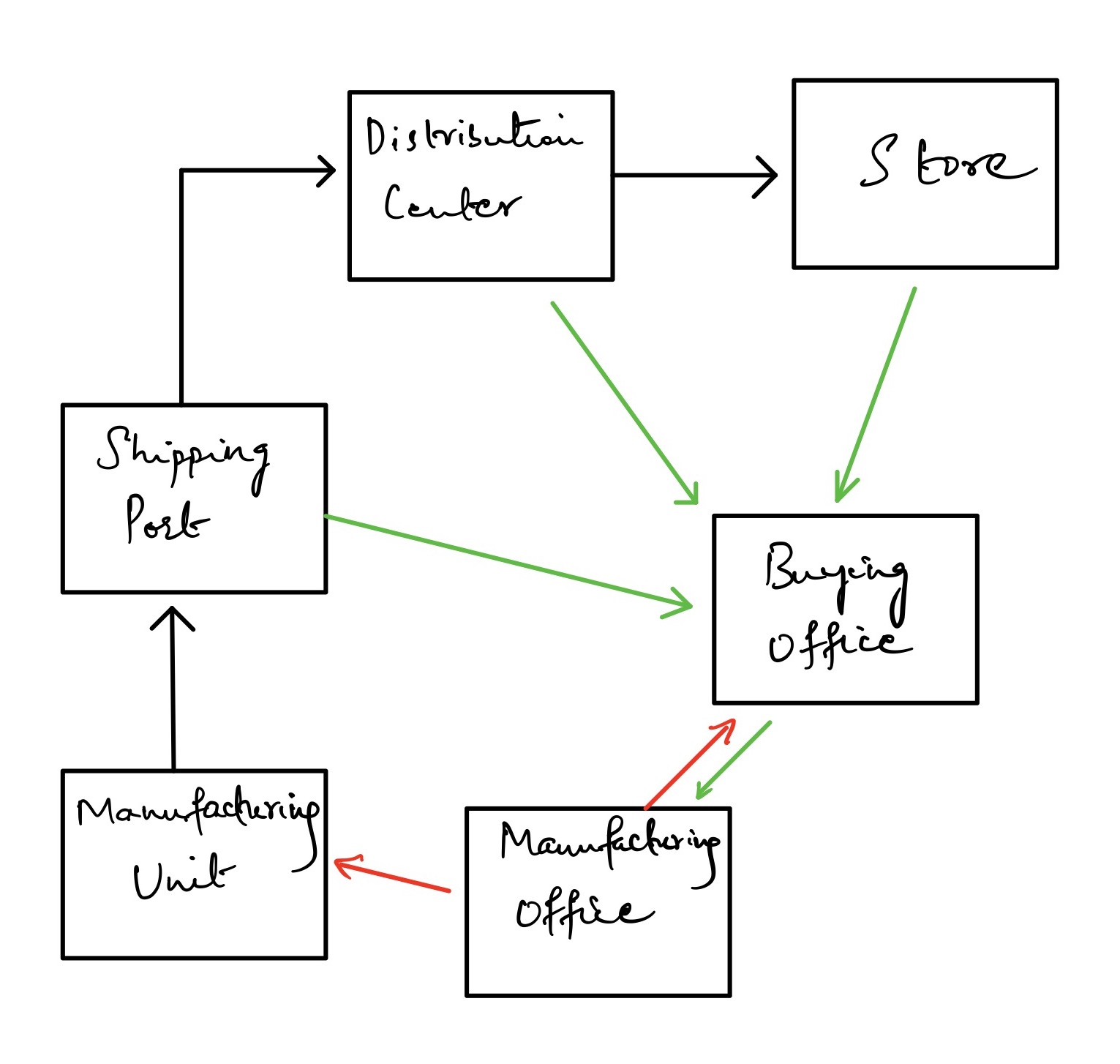

The flow above shows an ideal world scenario of garment manufacturing. I call it an ideal world scenario because I’m hiding all the complexity.

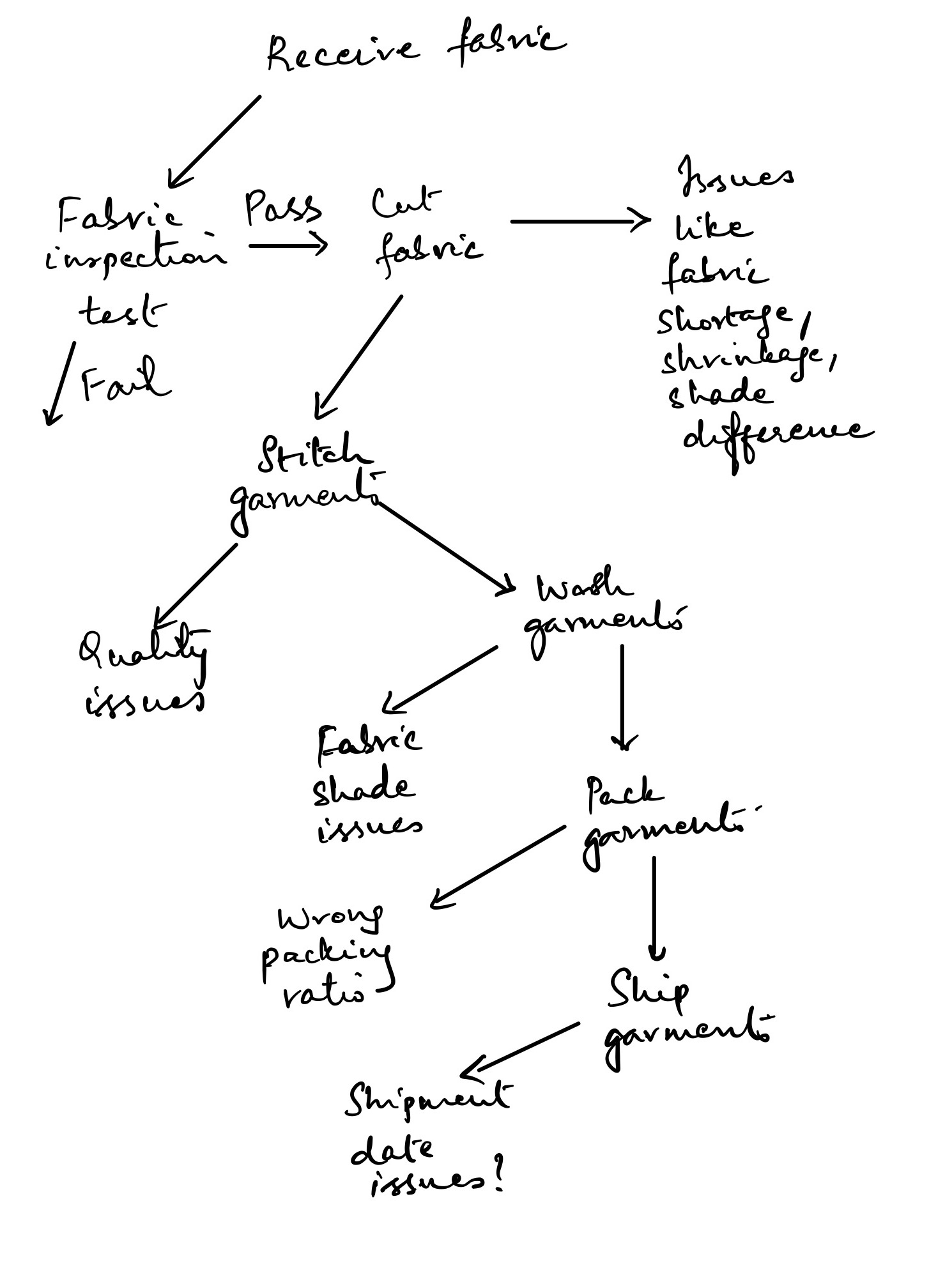

Below is another flow which shows how it actually goes

You’ll notice most of the complexity has been added by quality checks at different stages of the product. Additionally, lead times have been shrinking in the garment manufacturing industry which doesn’t help when trying to deal with this complexity.

The Communication Gap

So, how would the second flow go?

Well, first the manufacturer order the fabric. The fabric gets delivered. However, the manufacturer find that some of the fabric doesn’t meet the requirements set out by Myntra. So, the manufacturer goes back to the fabric supplier and tries to get the fabric they actually want.

In the meantime, the manufacturer decides to start cutting the fabric received initially. However, midway through cutting the rolls, the manufacturer finds out there’s a shade difference between rolls of the same style and cutting comes to a halt. In the meantime, the lead time that the buyer provided (about 3 weeks) is running out.

All this time, Myntra believes that their order is on track. Little do they know of the challenges.

Now, the manufacturer gets the fabric they actually want. Cutting restarts in earnest. However, the shipment is already 2 days behind in a schedule that only lasts 21 days. Luckily, cutting goes off without a hitch.

Next comes sewing where the different parts are stitched together. But, now, a couple of the machines in a batch breakdown. It’s going to take a day to get them fixed. So, production halts again. Myntra still has no idea what’s going on. They’re blissfully unaware and expect their order to reach them in time.

Now, with 3 days lost, the manufacturer really needs to step it up so the buyer gets their goods in time. The remainder of stitching goes through without a hitch but the manufacturer is only able to get 90% of the order done by the date it should be shipped. The 90% reaches the inspection zone in the finishing section. Here, Myntra’s QA prevents it from going further because he claims that the finished garment has some defects.

So, those garments need to be re-stitched including the remaining 10%. Myntra is still living in blissful ignorance.

The goods are packed & shipped out. However, at the receiving port, Myntra to their dismay realise that they haven’t received their full order quantity. They get on the phone to the manufacturer and berate them. The manufacturer can’t do much except tell them that he will try to get it done as soon as possible.

Notice the biggest difference between your interaction with Myntra and Myntra’s interaction with a manufacturer? Notice the lack of communication? And remember what I said about communication breeding trust?

How different might have the situation turned out if Myntra was aware at all times about the status of their order? How different would it have been if they knew how much had been cut on a given day at any given time? How different would it have been if they knew that production had halted for a day? How different would it have been if they knew their appointed QA was rejecting garments in the finishing section? Could they perhaps have been better prepared for it?

Where Does The Internet Come In?

The internet’s greatest achievement is reducing friction in communication and that’s my goal: reduce friction in communication between manufacturers and brands.

So, how do we reduce communication friction? Through economies of scale. A platform is a classic example of economies of scale reducing friction.

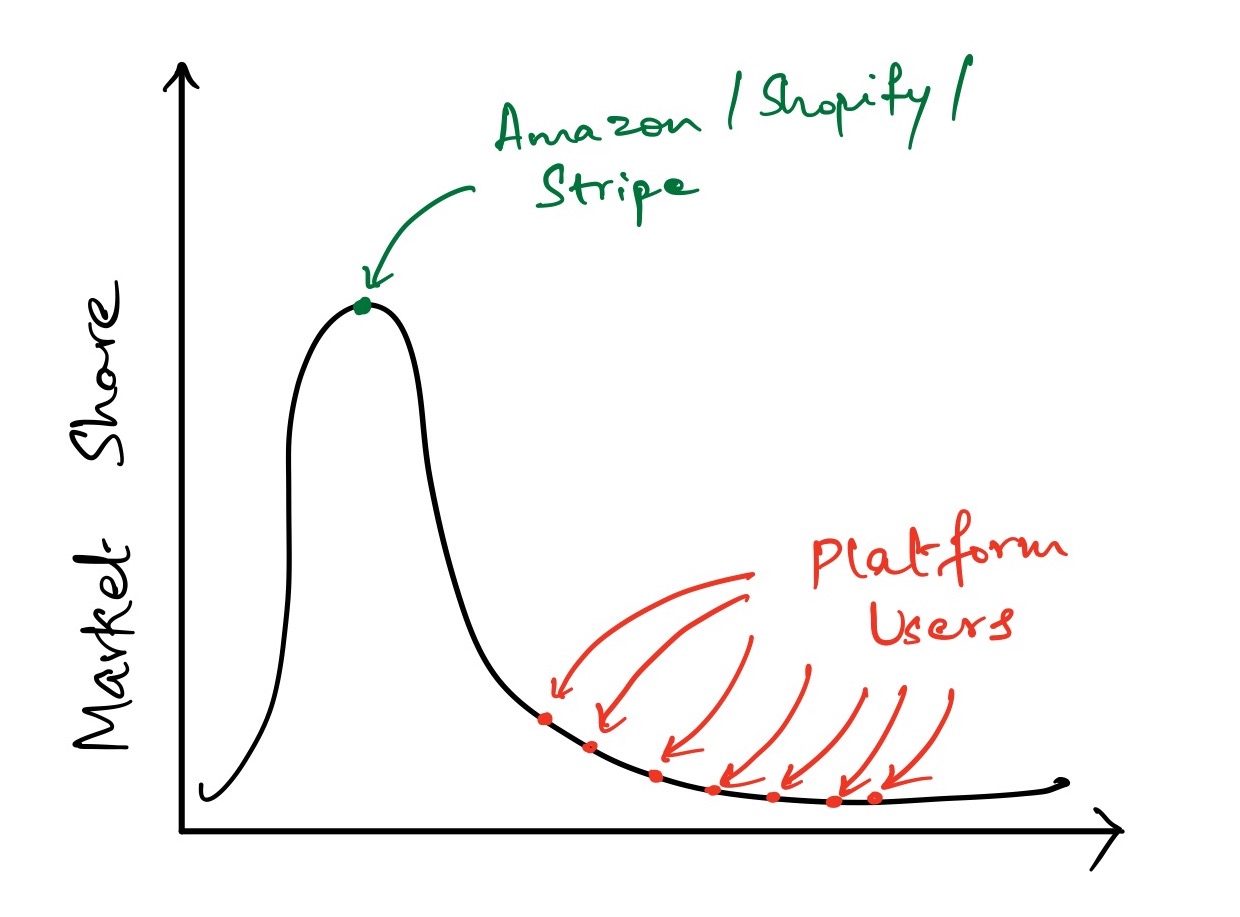

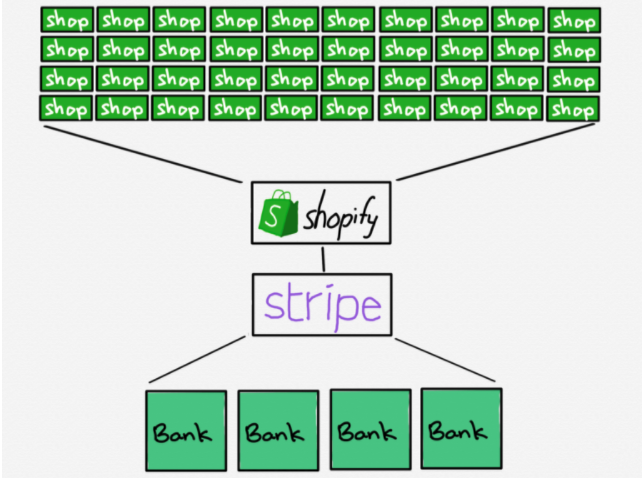

The visual above is my recreation of something I remember reading on Ben Thompson’s Stratechery newsletter (unfortunately, I can’t seem to find the link to the original graphic).

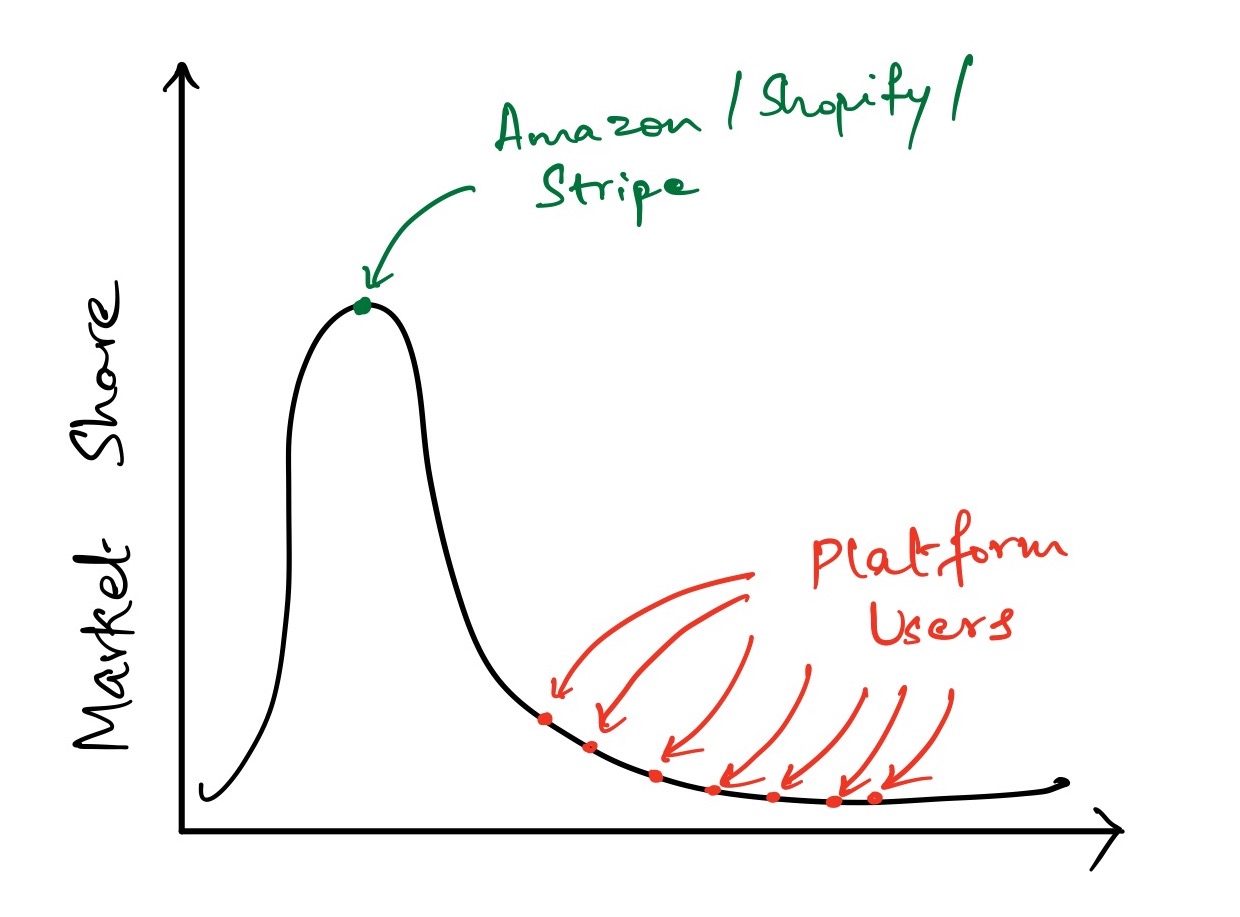

The gist of it is that platforms tend to dominate market share leaving behind a long tail of users of their platform that each dominate a much smaller percentage of the market share in the same domain.

Until platforms became a thing on the internet, the world tended to see a larger volume of companies dominate a smaller percentage of the market share each. Platforms, however, create a situation of extremes which lends itself well towards economies of scale.

So, how do we go about building the platform?

There are generally two approaches: a product first model or an API first model.

Again, this is courtesy of Ben Thompson’s newsletter Stratechery. In fact, Ben had a great piece about the difference between product first platforms like Shopify and API first platforms like Stripe that you can read here.

Essentially, product first platforms like Shopify allow users to set up a merchant store at the click of a button and start selling online without getting into the technical details of things.

On the other hand, you have API-first platforms like Stripe that allow programmers to build products on top of the infrastructure Stripe offers.

Two very different solutions to building a platform. However, I can’t ignore the fact that Stripe is a FinTech company in the payments industry that has traditionally always adopted technology far quicker than most other industries.

Why? If I had to guess, I’d say its because payments today involve a primarily digital asset that can be programmed easily. You can’t program a physical good, like a garment, simply because its physical.

So, the question then becomes, if I were to set up a manufacturing platform, should it be via a product or an API?

The end consumer for this platform will be buying houses like H&M, GAP, Old Navy, Zara etc. While these companies have done well by adopting technology and hiring programmers, they are far behind their FinTech counterparts. An API first product in this space would be premature.

What Should The Platform Do

What should the platform do? I’m going to work towards that from what we’re solving: namely the communication between buyer & manufacturer.

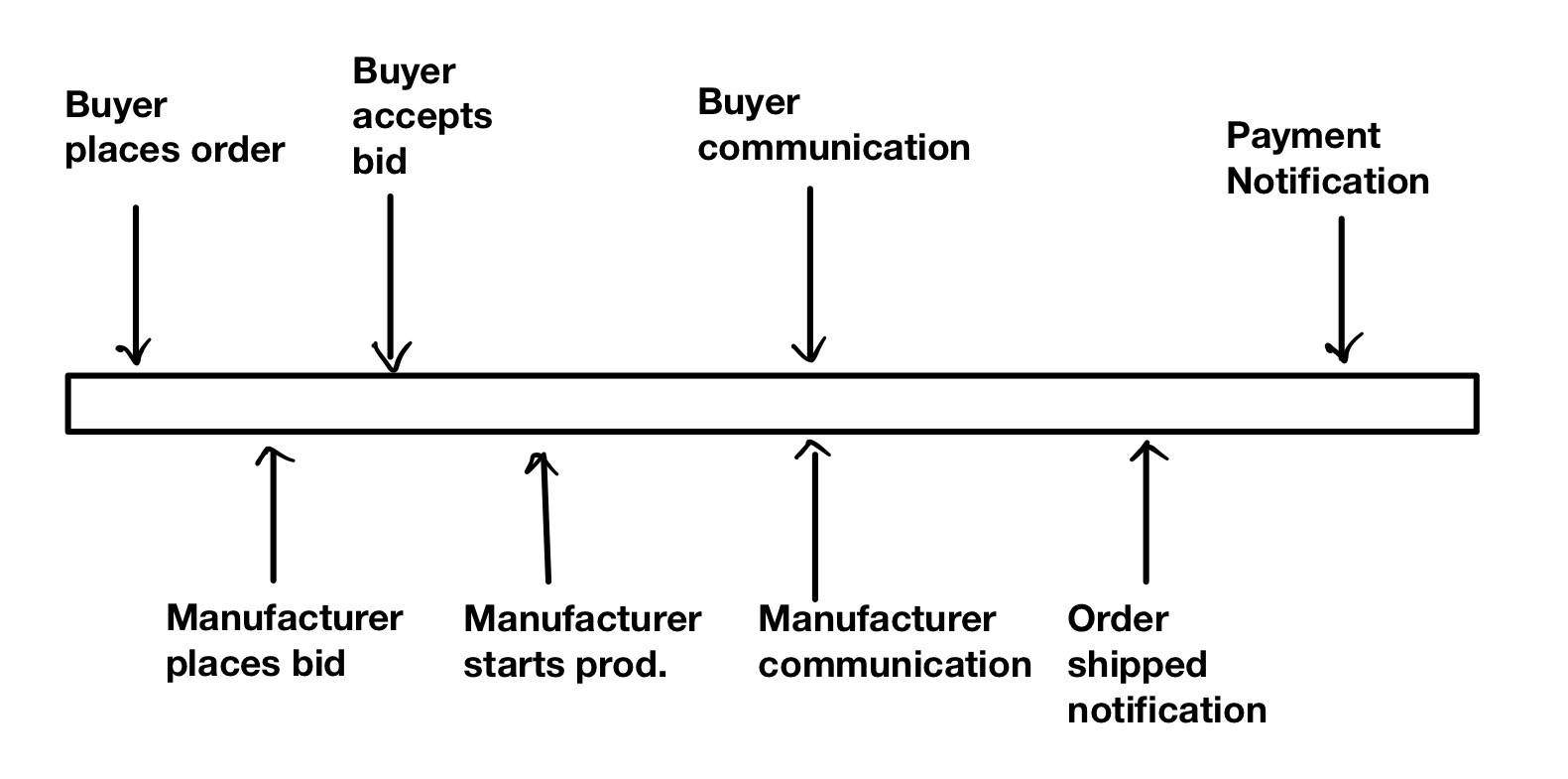

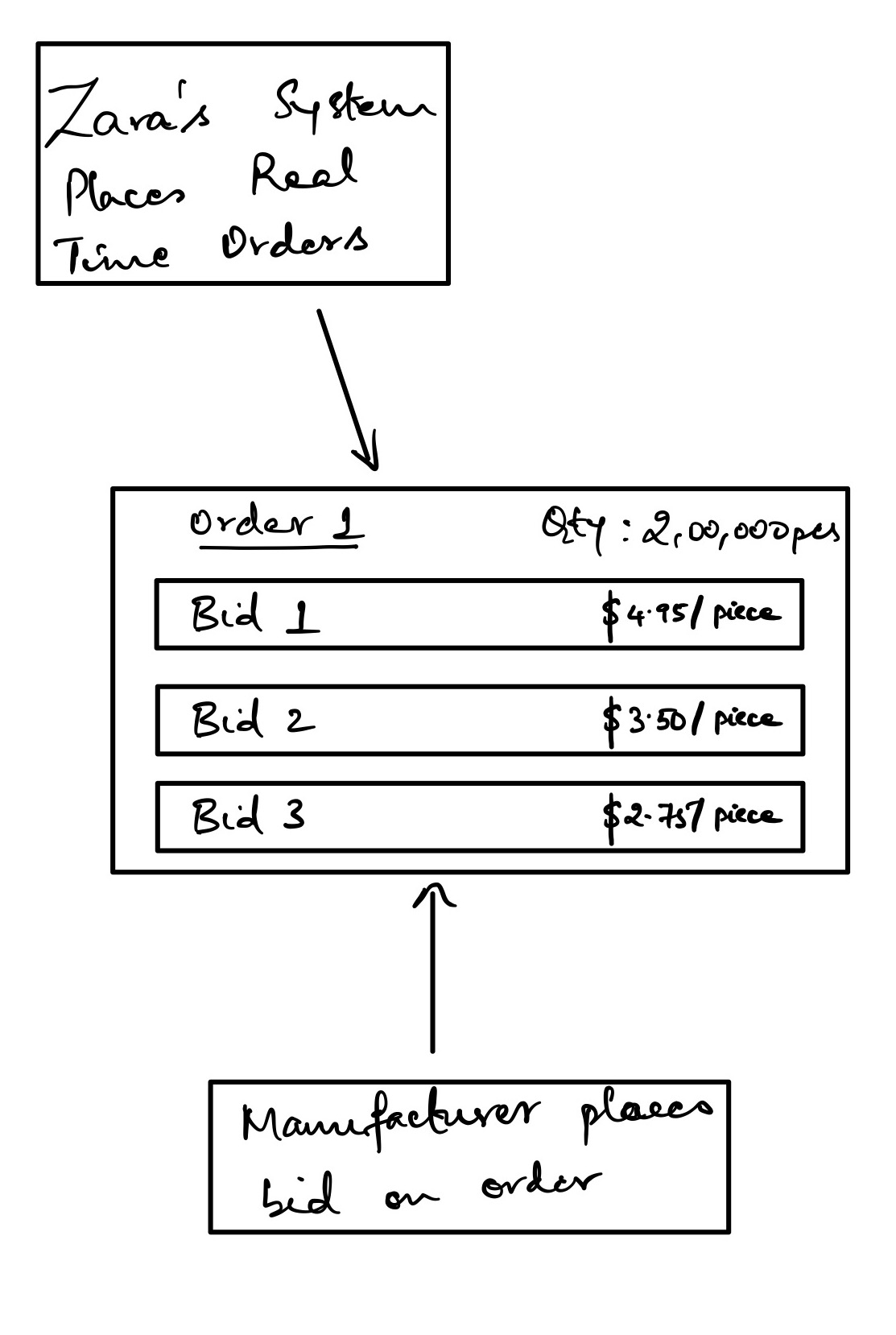

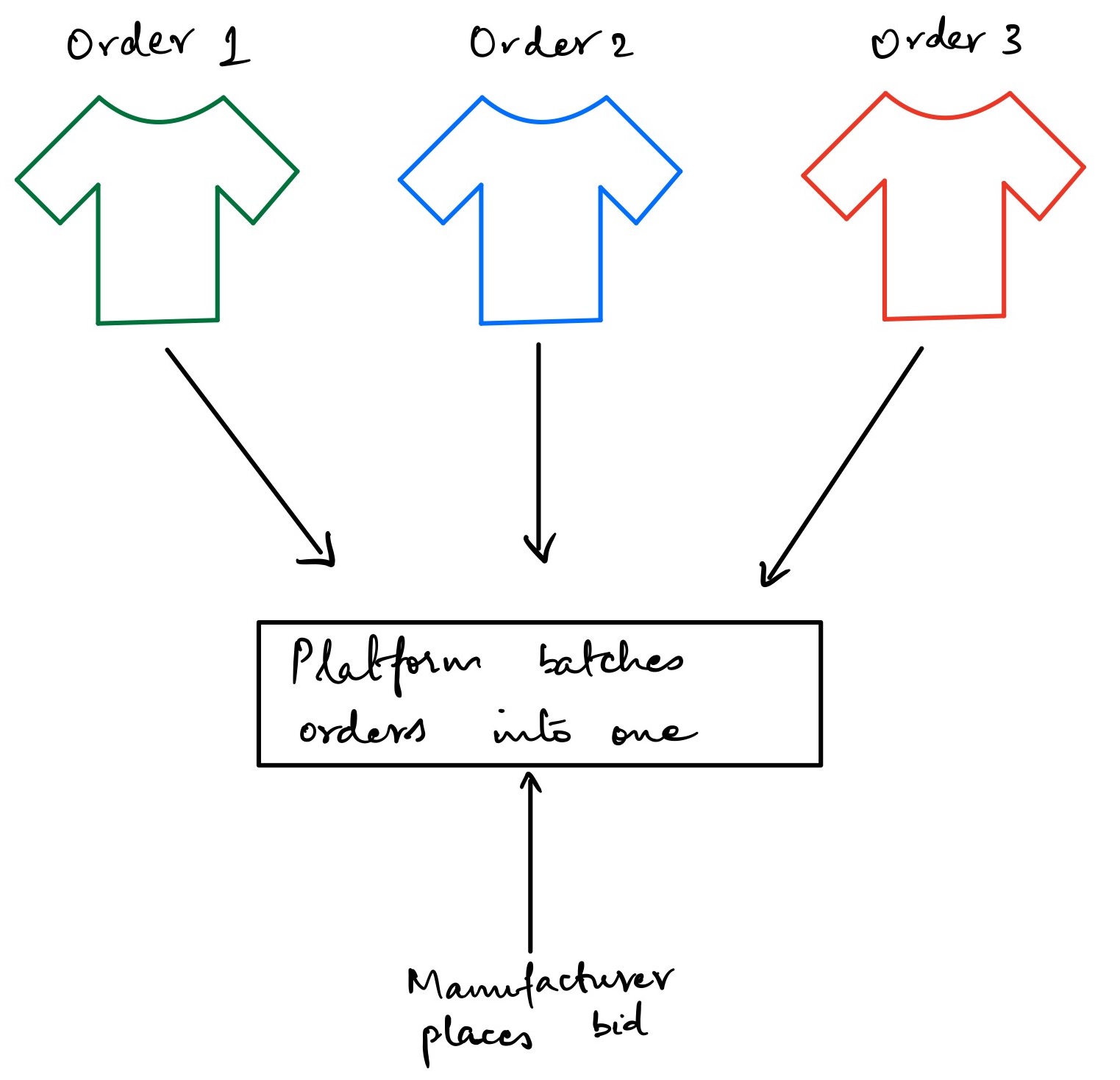

The sketch above shows what the inter-communication between the buyer and the manufacturer would look like. You’ll notice that I’ve included bidding and payments on the platform and I really want to get into that.

While providing a communication interface between buyer & manufacturer will be important, the platform can be extended to also serve as a payment gateway and it’ll be a far more effective one.

Why will it be more effective? Let’s examine the current state of payments.

The Payment Cycle

We examined an order earlier which had a ratio set like below

Country S M L XL

USA 100 100 400 200

Russia 100 100 250 50

China 300 300 100 0

So, the USA needs to get a carton with 100 pieces of S, 100 piece of M, 400 pieces of L and 200 pieces of XL of the product.

Payment is usually based on goods being shipped on time. Once the goods reach the destination port, the payment is sent out in 30-45 days based on the agreement between the buyer & manufacturer.

Currently, this is a process fraught with complexity and a dreaded amount of “follow-up”. Both parties have legitimate complaints when it comes to payments.

Brands sometimes claim that they haven’t received all the goods on time. For instance, if a carton marked for the USA was supposed to have the quantities per size denoted above in it, at the receiving port they might inspect it and realise that there are only 350 pieces of L.

Manufacturers, on the other hand, insist that the correct number of garments were packed in the carton and something must have gone wrong in between (which isn’t unheard of). There are also instances of buyers not honouring the terms of their agreement and delaying the payment to a manufacturer which causes cash flow issues for the manufacturer.

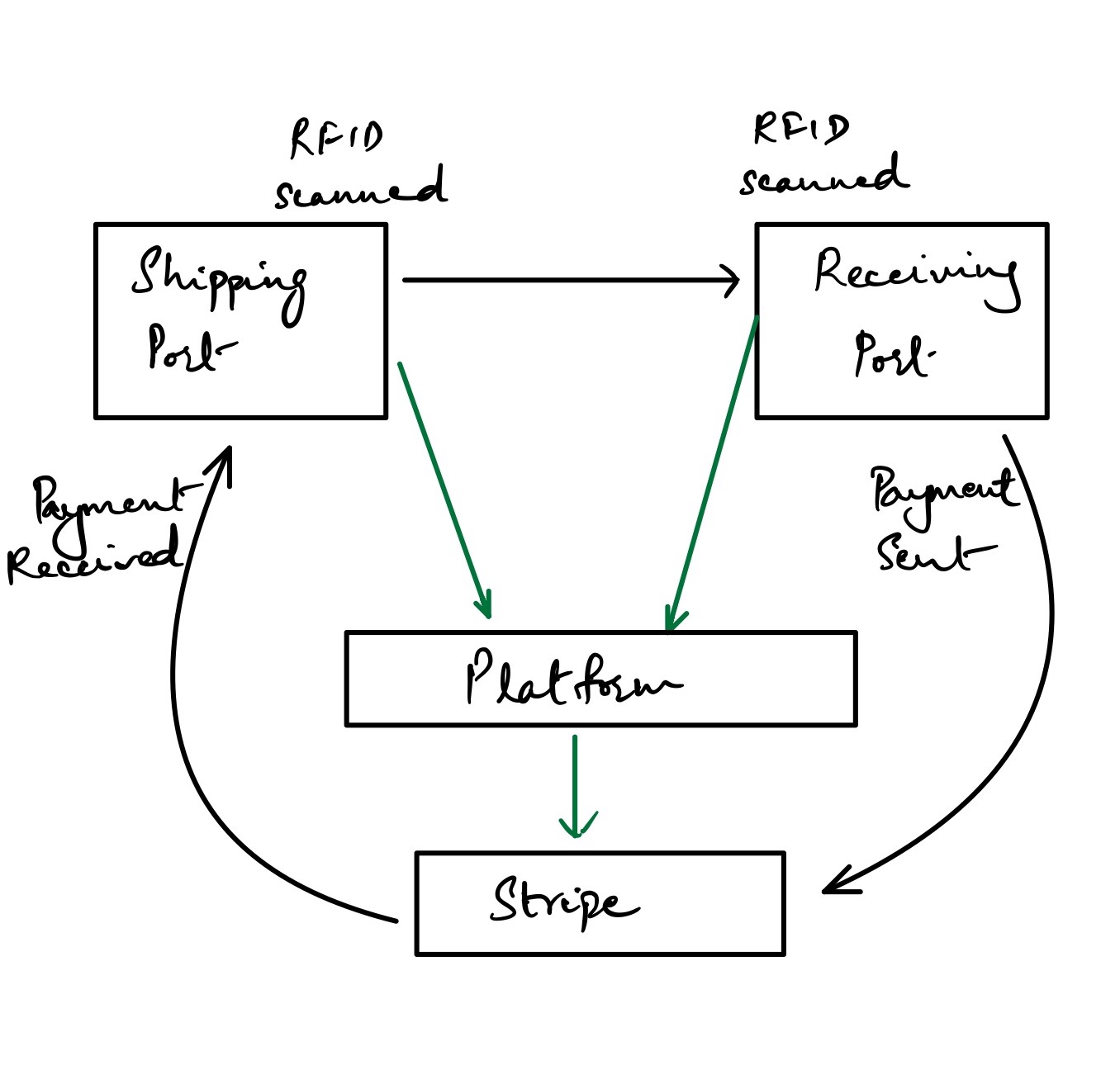

Now, I am going to show you why I added payments to the platform. Imagine a scenario where all goods have RFID’s attached to them (more and more brands are adopting this). These tags can be be scanned at the shipping port and the destination port. If both ports confirm the number of RFID’s scanned as equal, the platform immediately triggers a payment contract release via a Stripe integration (read here to see how its done) from the buyer to the manufacturer.

The contract can be programmed to release the payment immediately after 30-45 days and can perform basic checks like ensuring there is enough balance in the checking account of the sender to clear the payment. This gives both parties relief in knowing exactly what stage of the payment cycle they are in and knowing that the payment is guaranteed to occur on time.

Now, that payment can be completed after 30 or 45 days, whatever the payment cycle agreement between the two parties involved are. You can even add any additional number of triggers between the two parties, like the garments having to pass a quality check before payment will be completed.

This is the secret sauce behind a platform. By having economies of scale, it becomes possible to add multiple functionalities that users will find useful and have everybody enjoy them. It would be impossibly hard for an individual manufacturer to set up this sort of integration for each one of their buyers. However, by having all the manufacturers & buyers be on one platform, this becomes more feasible to accomplish.

Information Freedom

Why do businesses adopt new technology? Where is the benefit? From a cost perspective, in the immediate term, it doesn’t make sense. From an organizational point of view, it requires significant mental effort to make the new technology a part of standard operations. This effort is directly proportional to the scale of the organization.

I think it has to do with the freedom of information and the more effective communication that arises as a result of this. The hope is that the more effective communication can lead to a greater operational efficiency which will result in an eventual ROI.

I’ve repeatedly said that communication is the be all and end all of organizational effectiveness and I really do think that’s one of the biggest benefits of information technology, albeit as a 2nd order effect.

Information wants to be free - Stewart Brand

Let’s try and apply this from the perspective of a brand that has their manufacturing done in factories all across India (like Zara). How does information freedom help them?

Let’s run through the above image really quickly for that. Zara wants information from their store about what styles are selling really well in-store. They want to know this because:

- They want to know what styles are their cash cow

- They want to know which new styles are gaining traction

- They want to know where to focus their attention

A dead simple solution would be to have a store clerk in each store keep track of which styles sell per day on pen and paper and fire off an email to the head office.

Like I’ve said before in this post, scale changes problems. This solution would work fine as long as there are 5-10 stores. The moment you realise that Zara has thousands of stores across the world, this breaks down.

Now, add an RFID tag to every garment and you have real-time analysis again. The first thought that crops up is, will the cost of the RFID be offset by the gain in margins as a result of real-time information access? The fact that Zara is already doing this should be evidence enough that it makes economic sense.

Once Zara has real-time information, communication within the company and with their manufacturers speeds up, leading to faster replenishment of styles.

The Bidding Cycle

One of the biggest problems any clothing brand faces is making sure their inventory is in stock and reaches the customer in time. The worst possible customer experience is seeing a product you want which is not in style, second only to not receiving delivery on time after you’ve paid for your product.

Since Zara has real-time data on which products are selling out in which parts of the world and even how quickly they are selling out, they can respond much more quickly to keep their styles in stock.

What is stopping them from placing real-time orders on a platform and opening them up for bidding from manufacturers? The lack of an option to do so.

A customer walks into a Zara store in Spain and picks out a plain white t-shirt and purchases it. The moment the RFID tag is removed, the sale is recorded in Zara’s database and the inventory is updated to reflect that.

Zara could add that quantity to any open orders on the platform that have not been closed yet. In the mean time, manufacturers can continue bidding on the order. Once Zara is ready for the order to go through they can pick the bid they like based on metrics like price and manufacturer reliability.

Typically, the way brands place orders is by picking the manufacturer based on certain requirements (like geographical location, pricing & reliability). This typically involves a marketing effort on the part of the manufacturer and background checks on the part of the buyer. All this is done to establish trust.

Once the brands have picked the manufacturer, the brands inform the manufacturer what orders they plan to give them. I’m going to refer to this as a “push” system because the buyers are “pushing” these orders onto the manufacturers.

Implementing a bidding system would invert that scenario.

If buyers place open orders that can be bid upon, manufacturers can then bid on orders and “pull” in the orders they want.

The main differences between the “push” and “pull” systems are:

- It reduces the amount of effort on the buyers part

- It improves discoverability for manufacturers so it reduces their marketing effort

- It opens up the possible list of manufacturers buyers could work with

The most critical factor, however, would be the trust between the manufacturer and buyer. How do the buyers know which manufacturer to trust?

Establishing trust is the job of the platform! In the same way you, as a consumer, trust Amazon and not the seller on Amazon, Zara and H&M would trust the platform and not the manufacturer on the platform.

Making sure that only trust worthy manufacturers are on the platform would be the job of the platform!

Extending The Platform

But, let’s go one step further with the platform.

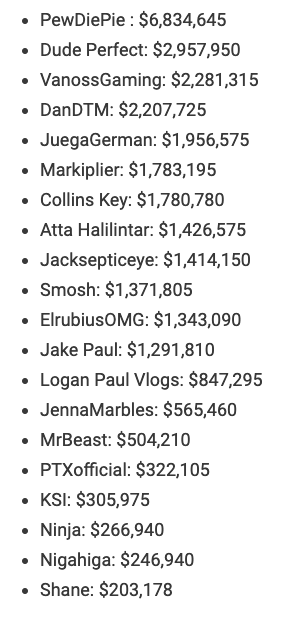

For this part, I want to look at how much merchandise PewDiePie, world famous YouTuber, sells.

Source for image here

PewDiePie sells about $6,834,645 worth of merchandise a month. Let’s say 75% of that is just from t-shirts, which brings us to $5,125,983. I’m going to pull out another magic number and say that 50% of clothing sales is just from t-shirts which is $2,562,991.

Now, if you look at PewDiePie’s official site, the cost of a t-shirt is 30$ pre-tax. This means he is selling approximately 85,433 t-shirts a month.

So who is manufacturing for PewDiePie? Who is manufacturing for the hundreds and thousands of other online celebs who are constantly looking to drop merch? Numbers from an individual celebrity might seem small but think about the number of celebrities out there.

I’ve found one example of a site that allows users to design and ship their own clothes. A site like this could easily be integrated onto a manufacturing platform. The prices being offered currently wouldn’t even compare to what could be offered by large scale manufacturers.

However, there is a problem that needs to be tackled first.

In the world of garment manufacturing, 85k t-shirts (and this would be the maximum since PewDiePie is at the top of the list) is a relatively small number and the economies of scale the manufacturer would get by doing the same style repeatedly wouldn’t apply in this case.

However, there are two possible ways to re-frame the problem.

Batching Similar Orders

The problem with doing low-volume manufacturing in the garment industry is a problem of manual labour.

For specific garments, the stitching machines need to be changed and the operators need to change the operations they are doing.

This introduces a time lag called turn-around time where the productivity drops while the operators get used to the new operations they have to perform.

Now, some claim that this is a mentality issue and that it can be solved by pushing the labourers. Unfortunately, fighting mentality is usually a lost cause and best saved as a last resort.

In a situation where there are multiple orders from many YouTube celebrities, the type of garments are bound to be similar. They are probably going to be t-shirts where the only thing that changes is the print.

The reason that its going to be t-shirts is because, while brands sell themselves on the style of garments they can offer (along with brand value), a YouTuber is going to sell clothing based entirely on brand value. Nobody really cares that PewDiePie’s t-shirt is made of a different kind of cotton than Mr. Beast’s t-shirt. People want to support their favorite YouTuber by buying their merch.

So, what we end up with is a t-shirt that is identical between YouTubers with the main difference being the print on the t-shirt itself.

With the t-shirt styling being similar and the biggest difference coming from something like colour, multiple fabrics can be cut and stitched at the same location. This re-introduces economies of scale and having workers operate on similar styles can help improve their productivity and reduce costs.

The platform can help with this because all orders put up by brands / celebrities can be categorized based on metrics like style, cut and colour. Once the categorization is done, similar orders can be batched together to create larger volume orders. Manufacturers can then bid on these larger volume orders and re-introduce economies of scale.

Small Manufacturers On The Platform

An alternative way to solve this problem would be to simply have up-and-coming manufacturers on the platform. Smaller manufacturers will not have the capability of doing larger volume orders so it would make sense for them to take on orders of this size.

This would also boost small businesses and encourage them to enter the garment manufacturing industry. Currently, it is extremely hard for an incumbent to enter this industry. Part of the problem is economies of scale which don’t support smaller players and another part of the problem is discoverability. Where do these incumbents begin getting their orders from?

In an episode of Masters of Scale, Tobi Lutke the founder of Shopify, talks about how Shopify’s goal was to increase the number of online stores by allowing anyone to become a merchant. Shopify has made it so easy for anyone to open an online store and start selling their goods that this has led to an explosion in independent businesses, especially among clothing brands.

I bring up Shopify here for two different reasons:

- Shopify increased the number of online stores by making it easier to setup an online store

- Shopify as a platform wants other platforms to integrate with them

Shopify’s fashion industry report states that the industry is expected to hit $712.9 billion by 2022. In the same report, they also note that “lower digital barriers to entry for all clothing merchants offer the opportunity to market, sell and fulfill orders globally and automatically.”

With this explosion in online brands, who is manufacturing for these brands? Who is providing the infrastructure for these brands so they can focus on the customer experience? How easy is it for these brands to find manufacturers? What kind of prices are they getting? Are these prices competitive?

If there were to be a manufacturing platform, couldn’t this platform allow for a similar growth in manufacturers similar to the way Shopify did for online merchants?

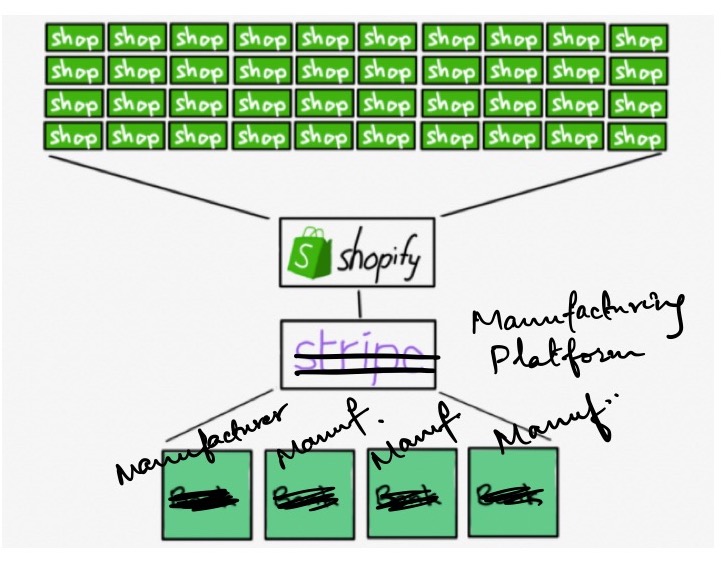

In another brilliant piece, Ben Thompson notes that Stripe is becoming a platform of platforms. Now, everyone who signs up for a Shopify account also gets a bank account set up immediately courtesy of Stripe at the click of a button.

Image courtesy of Stratechery

I’ve made some slight edits to the image above, as you can see below

Now, every merchant who signs up for Shopify and wants to set up a clothing brand will automatically have access to a wide array of manufacturers to choose from. The manufacturing platform will provide the infrastructure to allow them to succeed by evening the playing field between them and the brands that have had decades to establish themselves.

With a greater demand for manufacturing, there is an incentive for more people to enter the garment manufacturing space.

This is the end goal of the introduction of computing into the public space. Have machines talking to each other everywhere possible except where human interaction is an absolute must.

Human interaction is an absolute must in designing a customer experience. It is going to be impossible to replace the marketing and brand value through current AI. When we hit that point, we’ll have much bigger problems to worry about.

Risks

The absolute biggest risk with trying to build a platform at internet scale is, ironically, also the biggest attractor.

In platform wars, it is almost always winner takes all. This is simply because for any platform to succeed it needs to have network effects and competition always fragments network effects. Eventually, what occurs is the graph I showed at the beginning of this post which I’m displaying again below

There is one behemoth that dominates market share in a specific field with a long tail of the various users of that platform.

But, its precisely the risk of winner takes all mentality that makes building a platform so attractive. Successfully building a platform will unlock economies of scale that will allow an entire new generation of merchants to create clothing brands that can rival the old guard and truly usher manufacturing into the internet age.