Async Runtimes Part III

Here’s a link to the code on GitHub.

This post is the third in a series about exploring what exactly an async runtime is, and what async I/O really means. Here is a link to part I where I built a basic future in Rust and polled it to completion with an executor, and here is part II, where I built a simple event loop which uses the kqueue async io interface.

In this post, I’m going to combine learnings from both posts to build a simple, single-threaded async runtime in ~900 lines of Rust code.

All of this started with some fundamental questions I had about what exactly the term “async” means, what fibers, coroutines, green threads etc. really are.

Async Words

I want to first explore the terminology used in async because having a shared vocabulary makes it much easier to have abstract conversations. While it might just sound like jargon or yak-shaving, being able to clearly differentiate things in designs or conversations is critical because abstractions quickly pile on.

You are quite likely to come across different definitions for the same term. For instance, Tokio docs call their tasks green threads but depending on what definition you go with that is not entirely accurate.

In this post, we'll use the definition of green threads that specifically means stackful coroutines.

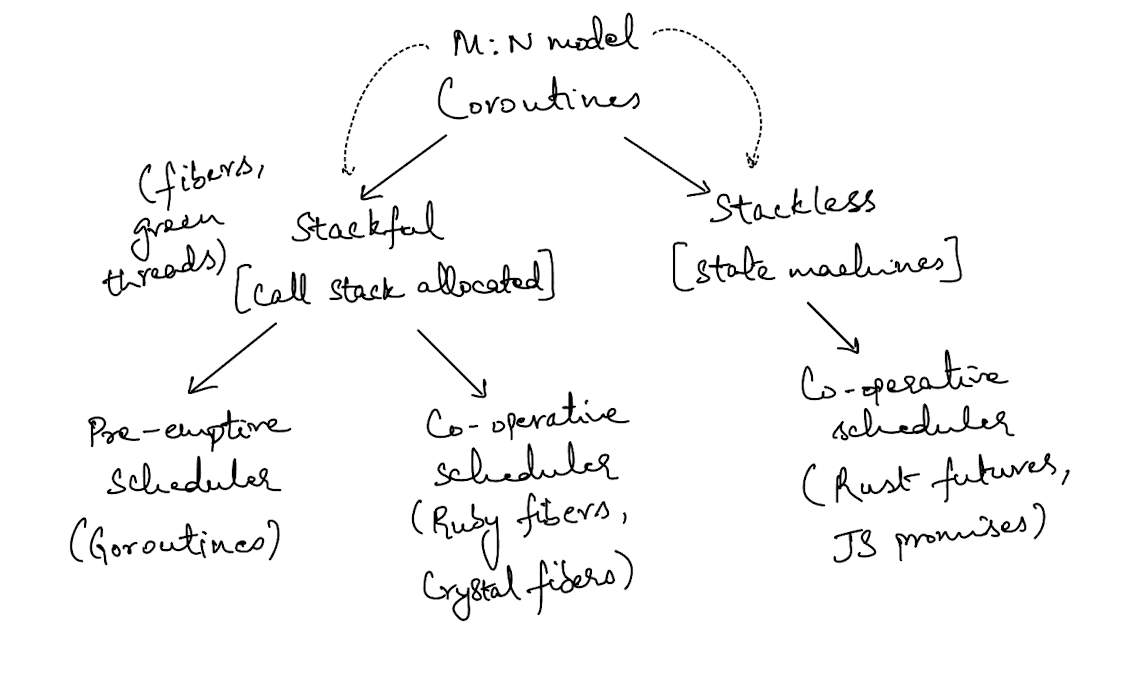

The image above gives a high-level overview of the state of async terminology. The broadest classifier of things are coroutines, of which there are two - stackful & stackless.

Stackful coroutines are usually referred to by other names such as fibers or green threads. Stackless coroutines are just state machines under the hood, and they are sometimes called tasks. Both styles of coroutines are sometimes referred to as using the M:N threading model, where M user-space threads or tasks are multiplexed onto N threads of the underlying host system (thanks to King Protty for pointing this out on Twitter).

The primary difference between the two types of coroutines is in the name - stackful have call stacks allocated (similar to OS thread stacks), stackless have no call stacks allocated to them.

Now, there are broadly two classes of schedulers(sometimes referred to as executors or runtimes):

- Pre-emptive

- Co-operative

Pre-emptive schedulers mean that the scheduler is capable of making a coroutine pause at any point during it’s execution. Co-operative schedulers mean that the scheduler is incapable of making a coroutine pause at any point during it’s execution, the coroutine is responsible for pausing at certain points so that it doesn’t block the scheduler.

With stackful coroutines, it is possible to have either a pre-emptive or co-operative scheduler (this is more of a spectrum, not binary). But, with stackless coroutines, you can only ever have a co-operative scheduler. The reason is that stackless coroutines compile down to state machines which don’t have a call stack allocated to them that stores execution information, so you can’t pause them at any point. Stackful coroutines on the other hand do have a call stack allocated to them which stores execution information. This allows the scheduler to stop & resume them at any point.

[From the OSTEP book]

We’ll dig deeper into stackless coroutines and co-operative schedulers in this post, but if you’re interested in learning more about stackful coroutines, I highly recommend chapter 4 of Asynchronous Programming in Rust.

Stackful & stackless coroutines have a famous allegory associated with them thanks to Bob Nystrom’s What Colour Is Your Function blog post from back in 2015. In the post, he presents the case for why he thinks stackless coroutines are the wrong abstraction to represent concurrency in a language.

Let’s look at some examples - consider the Go code below

package main

import "fmt"

func f(n int) {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(n, ":", i)

}

}

func main() {

go f(0)

var input string

fmt.Scanln(&input)

}

It kicks off a goroutine in the background and waits for some input from the user. Notice that you don’t have to do anything explicit in terms of making this asynchronous apart from using the go keyword. The functions have no “colour”.

Now, here is the equivalent JavaScript code (I’m using JS here because it’s syntactically easier to parse than Rust). Now, you use the async keyword to denote that some function can run in the background and it needs to have await called against it.

const readline = require('readline').promises;

async function f(n) {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(n, ":", i);

// Simulate some asynchronous work

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 100));

}

}

async function main() {

// Create a promise that resolves when f(0) completes

const task = f(0);

// Set up readline interface

const rl = readline.createInterface({

input: process.stdin,

output: process.stdout

});

// Wait for user input

await rl.question('Press Enter to exit...');

// Close the readline interface

rl.close();

// Ensure f(0) has completed

await task;

}

(async () => {

try {

await main();

} catch (error) {

console.error(error);

}

})();

The biggest downside is that you also need to denote your main function as async now because you can never call an async function from a regular function. This is where your code gets “coloured”. This might not seem like a big deal but consider a situation where you are trying to do simple iteration in your code but need to call an async function there now. Now, your iteration code also requires async against it even if it doesn’t actually do any I/O waiting. It becomes hard to differentiate which parts of your code are actually doing I/O operations, which voids doing function colouring to begin with. Eventually, your code just ends up becoming the colour of async.

In the JS code, you’ll also notice await, which you can think of as the points at which this coroutine is yielding back to the scheduler (it’s similar to the yield keyword used in generators, and generators are similar to async functions).

This is why async/await is considered co-operative - the scheduler has no way of stopping a future/promise in the midst of it’s execution because there is nowhere to save it’s execution information so it can resume later.

In the equivalent Go code, there was no yield or await keyword - the language’s compiler allows each thread that is spun up to execute for some fixed amount of time before stopping it, which as of Go 1.19.1 is 10ms(source).

Because of these details, there is a lot more implicit “magic” happening with Go’s runtime but it’s probably safer because it’s harder to shoot yourself in the foot. Conversely with the async/await situation, things are more explicit, but one poorly misplaced synchronous operation between two await operations could block your runtime. Rust uses async/await but doesn’t bundle a runtime with the language and depends on the ecosystem to provide a runtime. This choice providers users more power since they can choose a runtime based on the workload but adds a lot of mental overhead (a recurring theme with Rust).

In a language without “coloured” functions, since each coroutine is allocated a stack to keep track of it’s execution status, there is more overhead which isn’t present for stackless coroutines. Therefore, you should be able to spin up a greater number of stackless coroutines thus providing greater concurrency (this statement is caveated by implementation details of the application itlsef, though. Just because you can spin up more coroutines does not necessarily mean you are actually providing more concurrency and therefore greater throughput).

There is a certain irony to the terminology here - runtimes without “coloured” functions spin up “green” threads, whereas runtimes with “coloured” functions have no colour to their tasks.

async/await but without function colouring.

Now that we’ve explored the differences between stackful & stackless coroutines, let’s get down to building a simple runtime for stackless coroutines.

State Machines

The most important thing to understand when it comes to stackless coroutines is that they are typically compiled down to state machines which are then “run” to completion.

The important thing to note here is that the moment you use the async keyword in Rust, the compiler transforms that into code that resembles a state machine. Look at this Rust Playground link as an example. It just has the following Rust code

fn main() {

async {

println!("Hello world");

};

}

If you click the view MIR option in the playground, you’ll see the code generated by the compiler for the async block above.

The “run” to completion bit is important above because these state machines are lazy - they need to actually be run, sometimes repeatedly. This is the job of the executor/scheduler.

Taking a more complete example involving Rust futures, consider the code below

async fn example() {

let a = async_fn_1().await;

let r = sync_fn();

let b = async_fn_2().await;

}

which will compile down to something resembling the following

enum ExampleState {

Start,

AwaitingFutureA,

AwaitingFutureB,

Done

}

struct Example {

state: ExampleState,

output: Option<()>,

}

impl Future for Example {

// the logic to move the state machine through it's various states

}

Rememeber that Rust futures are stackless coroutines that cannot be pre-empted by the scheduler. If your sync_fn() above takes too long, you are actually blocking this task and the thread of the executor this task is running on.

Building A Runtime

Let’s start writing some code to build a basic single-threaded runtime. Here are the major components we are going to be building:

- tasks (wrappers around futures)

- waker

- reactor

- sync thread pool

- executor

If you’re unsure what any of these terms mean, refer back to parts i and ii of this series

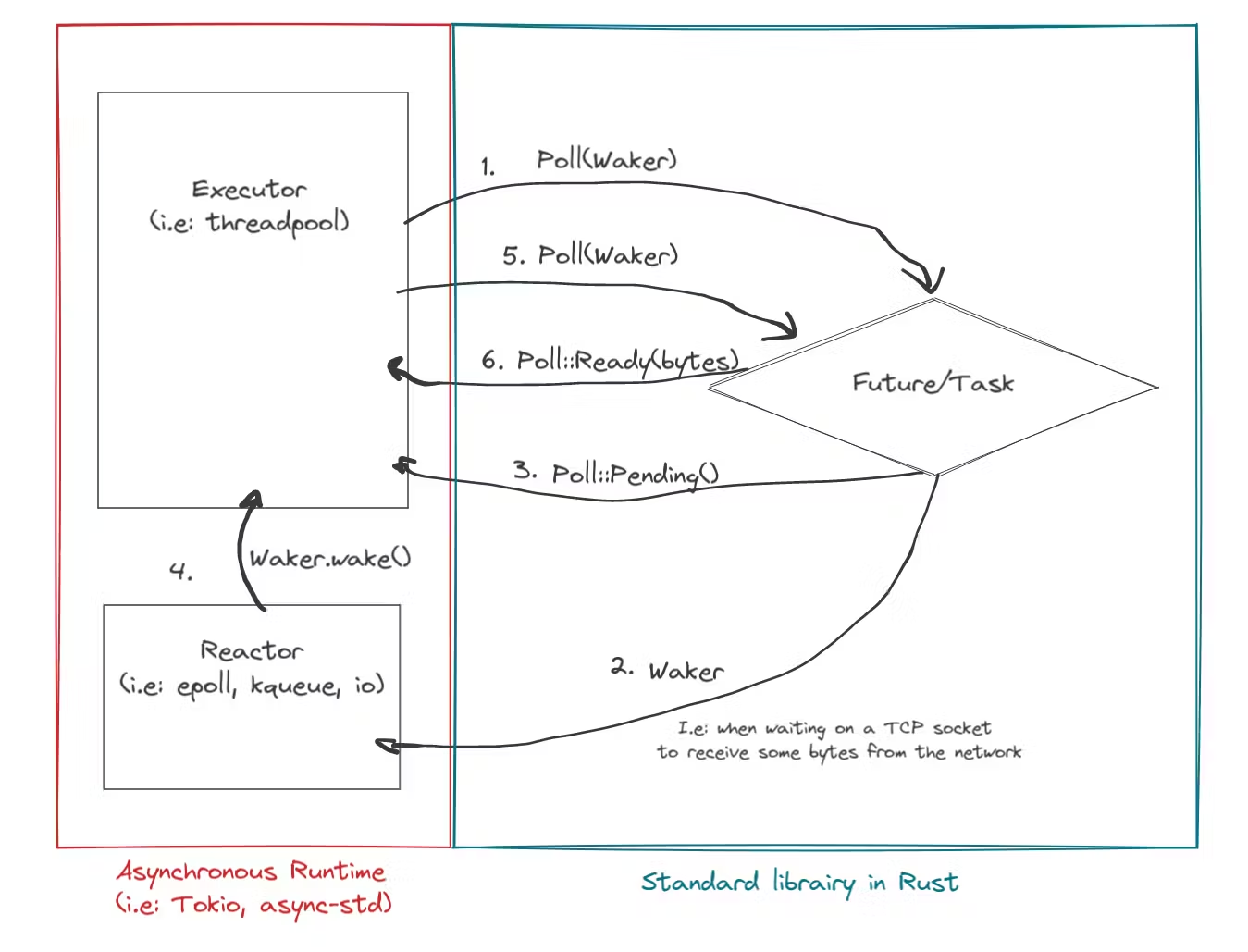

Here’s a great visual representation of what we’re trying to build using a TCP socket as an example.

We’ll tackle this component by component starting with actually representing our futures first.

Tasks

Representing tasks is fairly simple, they are just wrappers around futures with some additional metadata:

pub struct Task {

pub id: usize,

pub future: RefCell<Pin<Box<dyn Future<Output = ()> + 'static>>>,

}

impl Display for Task {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "task {}", self.id)

}

}

impl std::fmt::Debug for Task {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "task {}, ", self.id)

}

}

If you’re interested in understanding the Pin<Box<T>> verbosity, checkout fasterthanlime’s post. Put very simply, it’s to ensure that the future is not moved from the memory region it’s stored in.

Waker

The waker is probably the component with the most complicated code, mostly because I chose to implement it in unsafe Rust. If you’re following along and trying to build this on your own, you can always use the simpler ArcWake implementation. I chose not to do that mainly because I never intended to make this runtime multi-threaded and I like the masochism of unsafe Rust.

Before I jump into the code for the waker, I need to explain a fat pointer. A pointer is typically one word size since it only holds a memory address. However, a fat pointer is more than one word size since it holds a memory address and some additional data (in this case, a vtable).

Note: If you want to look at a better implementation of the code below, look at the std lib’s implementation

Here’s the code for the waker, and I’ll walk through it after

pub struct MyWaker {

task: Rc<Task>,

sender: Sender<Rc<Task>>,

}

impl MyWaker {

const VTABLE: RawWakerVTable =

RawWakerVTable::new(Self::clone, Self::wake, Self::wake_by_ref, Self::drop);

pub fn new(task: Rc<Task>, sender: Sender<Rc<Task>>) -> Waker {

let pointer = Rc::into_raw(Rc::new(MyWaker { task, sender })) as *const ();

let vtable = &MyWaker::VTABLE;

unsafe { Waker::from_raw(RawWaker::new(pointer, vtable)) }

}

unsafe fn clone(ptr: *const ()) -> RawWaker {

let waker = std::mem::ManuallyDrop::new(Rc::from_raw(ptr as *const MyWaker));

let cloned_waker = Rc::clone(&waker);

let raw_pointer = Rc::into_raw(cloned_waker);

RawWaker::new(raw_pointer as *const (), &Self::VTABLE)

}

unsafe fn wake(ptr: *const ()) {

let waker = Rc::from_raw(ptr as *const MyWaker);

waker.sender.send(Rc::clone(&waker.task)).unwrap();

}

unsafe fn wake_by_ref(ptr: *const ()) {

let waker = &*(ptr as *const MyWaker);

waker.sender.send(Rc::clone(&waker.task)).unwrap();

}

unsafe fn drop(ptr: *const ()) {

drop(Rc::from_raw(ptr as *const MyWaker));

}

}

I have a custom MyWaker struct which holds the task and a sender to a channel. Apart from that, there is the implementation of the dynamic virtual table.

The clone method above uses std::mem::ManuallyDrop to ensure that the default destructor for Rc doesn’t run when the scope ends (I spent 6 hours chasing down that bug).

The wake & wake_by_ref methods send the task onto a channel so that it can be polled by the executor.

Task Queue

I didn’t explicitly mention this component in the list above because it’s tiny and could typically be rolled into the executor. But, it’s where tasks are sent to & then read from. Fairly self-explanatory code.

pub struct TaskQueue {

pub tasks: Vec<Rc<Task>>,

sender: Sender<Rc<Task>>,

receiver: Receiver<Rc<Task>>,

}

impl TaskQueue {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let (sender, recv) = mpsc::channel();

Self {

tasks: Vec::new(),

sender,

receiver: recv,

}

}

pub fn sender(&self) -> Sender<Rc<Task>> {

self.sender.clone()

}

pub fn receive(&mut self) {

while let Ok(task) = self.receiver.try_recv() {

self.tasks.push(task);

}

}

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<Rc<Task>> {

self.tasks.pop()

}

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

self.tasks.len()

}

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

self.tasks.len() == 0

}

}

Reactor

I already covered reactors in detail in part ii, so refer to that if you want more detail. The big update to this component is that I now store the wakers that are built for each task, so that the task can be enqueued when the reactor receives an event.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct Event {

pub fd: usize,

pub readable: bool,

pub writable: bool,

}

impl Event {

pub fn none(fd: usize) -> Event {

Event {

fd,

readable: false,

writable: false,

}

}

pub fn readable(fd: usize) -> Event {

Event {

fd,

readable: true,

writable: false,

}

}

pub fn writable(fd: usize) -> Event {

Event {

fd,

readable: false,

writable: true,

}

}

pub fn all(fd: usize) -> Event {

Event {

fd,

readable: true,

writable: true,

}

}

}

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum InterestType {

Read,

Write,

}

pub struct Reactor {

kqueue_fd: RawFd,

notifier: (UnixStream, UnixStream),

readable: HashMap<usize, Vec<Waker>>,

writable: HashMap<usize, Vec<Waker>>,

}

impl Reactor {

/// Create a reactor instance

pub fn new() -> std::io::Result<Self> {

let kq = unsafe { libc::kqueue() };

if kq < 0 {

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

let (reader, writer) = UnixStream::pair()?;

reader.set_nonblocking(true)?;

writer.set_nonblocking(true)?;

let reactor = Reactor {

kqueue_fd: kq.as_raw_fd(),

notifier: (reader, writer),

readable: HashMap::new(),

writable: HashMap::new(),

};

reactor.modify(

reactor.notifier.0.as_raw_fd(),

Event::readable(reactor.notifier.0.as_raw_fd().try_into().unwrap()),

)?;

Ok(reactor)

}

/// Function to determine what interests this source has

fn get_interest(&self, source: usize) -> Event {

match (

self.readable.contains_key(&source),

self.writable.contains_key(&source),

) {

(false, false) => Event::none(source),

(true, false) => Event::readable(source),

(false, true) => Event::writable(source),

(true, true) => Event::all(source),

}

}

/// Function to register interest for a specific source

pub fn register_interest(

&mut self,

source: i32,

interest: InterestType,

context: &mut Context,

) {

match interest {

InterestType::Read => {

self.readable

.entry(source as usize)

.and_modify(|v| v.push(context.waker().clone()))

.or_insert(vec![context.waker().clone()]);

self.modify(source, Event::readable(source as usize))

.unwrap();

}

InterestType::Write => {

self.writable

.entry(source as usize)

.and_modify(|v| v.push(context.waker().clone()))

.or_insert(vec![context.waker().clone()]);

self.modify(source, Event::writable(source as usize))

.unwrap();

}

}

}

pub fn get_wakers(&mut self, events: Vec<Event>) -> Vec<Waker> {

let mut wakers = Vec::new();

for event in events {

if event.readable {

if let Some(readable_wakers) = self.readable.remove(&event.fd) {

wakers.extend(readable_wakers);

}

} else if event.writable {

if let Some(writable_wakers) = self.writable.remove(&event.fd) {

wakers.extend(writable_wakers);

}

}

}

wakers

}

pub fn waiting_on_events(&self) -> bool {

if self.readable.is_empty() && self.writable.is_empty() {

return false;

}

true

}

/// Function to accept the source to register an interest in and the type of interest

pub fn add(&mut self, source: RawFd) -> std::io::Result<()> {

self.modify(source, self.get_interest(source as usize))

}

/// A helper notify method to unblock the scheduler

pub fn notify(&mut self) -> std::io::Result<usize> {

self.notifier.1.write(&[1])

}

/// The function that removes interest for a file descriptor with the actual underlying syscall

pub fn remove(&mut self, fd: RawFd, ev: Event) -> std::io::Result<()> {

self.readable.remove(&(fd as usize));

self.writable.remove(&(fd as usize));

let registered_interest = self.get_interest(fd as _);

let mut changelist = Vec::new();

if ev.readable && registered_interest.readable {

changelist.push(kevent {

ident: fd as _,

filter: EVFILT_READ,

flags: EV_DELETE,

fflags: 0,

data: 0,

udata: ev.fd as *mut c_void,

});

}

if ev.writable && registered_interest.writable {

changelist.push(kevent {

ident: fd as _,

filter: EVFILT_WRITE,

flags: EV_DELETE,

fflags: 0,

data: 0,

udata: ev.fd as *mut c_void,

});

}

if changelist.is_empty() {

return Ok(());

}

let result = unsafe {

kevent(

self.kqueue_fd,

changelist.as_mut_ptr(),

changelist.len() as i32,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

0,

std::ptr::null(),

)

};

if result < 0 {

error!(

"There was an error while attempting to modify the kqueue list for {} for event {:?}",

fd, ev

);

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

Ok(())

}

/// The function that registers interest with the actual underlying syscall

fn modify(&self, fd: RawFd, ev: Event) -> std::io::Result<()> {

debug!("Adding file {} for event {:?} to reactor", fd, ev);

let mut changelist = Vec::new();

if ev.readable {

changelist.push(kevent {

ident: fd as _,

filter: EVFILT_READ,

flags: EV_ADD | EV_ONESHOT,

fflags: 0,

data: 0,

udata: ev.fd as *mut c_void,

});

}

if ev.writable {

changelist.push(kevent {

ident: fd as _,

filter: EVFILT_WRITE,

flags: EV_ADD | EV_ONESHOT,

fflags: 0,

data: 0,

udata: ev.fd as *mut c_void,

});

}

if changelist.is_empty() {

return Ok(());

}

let result = unsafe {

kevent(

self.kqueue_fd,

changelist.as_ptr(),

changelist.len() as i32,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

0,

std::ptr::null(),

)

};

if result < 0 {

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

Ok(())

}

/// Blocking poll function to get events

pub fn poll(&mut self) -> std::io::Result<Vec<Event>> {

let mut events: Vec<libc::kevent> = Vec::new();

let result = unsafe {

events.resize(1, std::mem::zeroed());

kevent(

self.kqueue_fd,

std::ptr::null(),

0,

events.as_mut_ptr(),

1,

std::ptr::null(),

)

};

if result < 0 {

return Err(std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

let mapped_events: std::io::Result<Vec<_>> = events

.iter()

.map(|event| {

let ident = event.ident;

let filter = event.filter;

if ident == self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd().try_into().unwrap() {

let mut buf = [0; 8];

self.notifier.0.read(&mut buf)?;

self.modify(

self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd(),

Event::readable(self.notifier.0.as_raw_fd().try_into().unwrap()),

)?;

}

let event = Event {

fd: ident,

readable: filter == EVFILT_READ,

writable: filter == EVFILT_WRITE,

};

Ok(event)

})

.collect();

info!("Received events {:?}", mapped_events);

mapped_events

}

}

The code above creates a kqueue file descriptor and then starts listening for events in one-shot mode on specific file descriptors. kqueue is only available on OSX & BSD distributions, the equivalent for Linux would be epoll but they provide a similar API.

The code also uses a Unix pipe hack to unblock the scheduler (I’ll show that below) since I just block the scheduler while listening for events from kqueue. I imagine that a production grade scheduler would typically provide a timeout.

Pay attention to the register_interest and get_interest methods here that update the readable & writable hash maps, this is where the wakers are stored.

epoll and kqueue fall under the readiness based model. These syscalls only indicate when a file descriptor is available to be read from or written to. There's the overhead of an additional syscall to actually do the writing or reading in this case. Because this API only determines readiness, it is mostly suitable for doing network operations - files are always considered "ready" to read from so there is no sense in wasting cycles polling their file descriptors.

io_uring on the other hand falls under the completion based model. This model involves providing the file descriptors you're interested in reading from or writing to along with a buffer into which the results can be written. It avoids the overhead of the additional syscall and also provides a unifying interface for both network & file IO operations. If you're interested, check out Jens Axboe's work on liburing

Sync Thread Pool

I mentioned earlier that we typically don’t want to block within our async code, but sometimes you need to perform a blocking operation, like reading from a file when io_uring isn’t available.

In these situations, it’s helpful to have a separate thread pool which can be used to run these blocking tasks in a non-blocking manner. This frees up the executor to run other tasks and check with this task periodically.

use super::reactor::Reactor;

pub struct FileIOPool {

sender: Sender<FileReaderTask>,

}

pub struct FileReaderTask {

pub path: PathBuf,

pub responder: Sender<std::io::Result<Vec<u8>>>,

}

impl FileIOPool {

pub fn new(num_threads: usize, shutdown_rx: Receiver<()>) -> Self {

let (sender, receiver) = channel::<FileReaderTask>();

let recv = Arc::new(Mutex::new(receiver));

let shutdown_rx = Arc::new(Mutex::new(shutdown_rx));

for _ in 0..num_threads {

let recv_clone = Arc::clone(&recv);

let shutdown_rx_clone = Arc::clone(&shutdown_rx);

std::thread::spawn(move || loop {

let task = recv_clone.lock().unwrap().try_recv();

let shutdown_signal = shutdown_rx_clone.lock().unwrap().try_recv();

match (task, shutdown_signal) {

(Ok(task), _) => {

let result = std::fs::read(task.path);

let _ = task.responder.send(result);

}

(_, Ok(())) => {

debug!("File io pool received shutdown signal, shutting down");

break;

}

(Err(_), Err(_)) => {}

}

});

}

Self { sender }

}

pub fn read_file(&self, path: PathBuf, reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>) -> ReadFileFuture {

let (file_completion_sender, file_completion_recv) =

std::sync::mpsc::channel::<std::io::Result<Vec<u8>>>();

let file_reader_task = FileReaderTask {

path,

responder: file_completion_sender,

};

self.sender

.send(file_reader_task)

.expect("Error while sending the file reader task to io pool");

ReadFileFuture {

reactor,

receiver: file_completion_recv,

}

}

}

pub struct ReadFileFuture {

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

receiver: Receiver<std::io::Result<Vec<u8>>>,

}

impl Future for ReadFileFuture {

type Output = std::io::Result<Vec<u8>>;

fn poll(

self: std::pin::Pin<&mut Self>,

cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>,

) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

match self.receiver.try_recv() {

Ok(data) => return std::task::Poll::Ready(data),

Err(e) => match e {

TryRecvError::Empty => {

debug!("received empty from the file reader task receiver");

self.reactor.borrow_mut().notify()?; // force the reactor to wake up so scheduler can continue

cx.waker().wake_by_ref();

return std::task::Poll::Pending;

}

TryRecvError::Disconnected => {

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(std::io::Error::new(

std::io::ErrorKind::Other,

"Received Disconnected while waiting for file read to complete",

)))

}

},

}

}

}

Every time the thread pool receives a task to read a file, it returns a future which can be polled to check whether the file reading has completed.

Executor

Finally, the center piece of all of this - the executor. There’s a lot of code here but it’s a simple component to understand. It’s simpler to think of this as a combination of 2 components:

- event loop

- futures poller

In the “hot” loop of this component, it listens for events from the reactor and also checks if the task queue has any tasks on it to poll, and it does this combination every iteration.

pub struct Executor {

task_queue: Rc<RefCell<TaskQueue>>,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

monotonic_clock: Mutex<usize>,

}

impl Executor {

pub fn new(

task_queue: Rc<RefCell<TaskQueue>>,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

) -> std::io::Result<Self> {

Ok(Self {

task_queue,

reactor,

monotonic_clock: Mutex::new(0),

})

}

pub fn block_on<F>(&self, future: F) -> F::Output

where

F: Future<Output = ()> + 'static,

{

let task = Task {

id: *self.monotonic_clock.lock().unwrap(),

future: RefCell::new(Box::pin(future)),

};

*self.monotonic_clock.lock().unwrap() += 1;

self.task_queue

.borrow()

.sender()

.send(Rc::new(task))

.unwrap();

self.run();

}

pub fn spawn<F>(&self, future: F) -> F::Output

where

F: Future<Output = ()> + 'static,

{

let task = Task {

id: *self.monotonic_clock.lock().unwrap(),

future: RefCell::new(Box::pin(future)),

};

*self.monotonic_clock.lock().unwrap() += 1;

self.task_queue

.borrow()

.sender()

.send(Rc::new(task))

.unwrap();

self.reactor.borrow_mut().notify().unwrap();

}

fn run(&self) {

loop {

self.task_queue.borrow_mut().receive();

loop {

let task = {

if let Some(task) = self.task_queue.borrow_mut().pop() {

task

} else {

break;

}

};

let waker = MyWaker::new(Rc::clone(&task), self.task_queue.borrow().sender());

let mut context = Context::from_waker(&waker);

match task.future.borrow_mut().as_mut().poll(&mut context) {

std::task::Poll::Ready(_output) => {

debug!(

"The future for task {} has completed and returned on thread {:?}",

task.id,

std::thread::current().id()

);

}

std::task::Poll::Pending => {

debug!(

"The future for task {} is pending on thread {:?}",

task.id,

std::thread::current().id()

);

}

};

}

self.task_queue.borrow_mut().receive();

if !self.reactor.borrow().waiting_on_events() && self.task_queue.borrow().is_empty() {

debug!("no events to wait on and no events in the queue, so breaking out");

break;

}

if self.reactor.borrow().waiting_on_events() {

debug!("waiting on events from the reactor");

match self.wait_for_io() {

Ok(events) => self.wake_futures_on_io(events),

Err(e) => {

if e.kind() == std::io::ErrorKind::Interrupted {

break;

}

eprintln!("Error while waiting for IO events :{}", e);

}

}

}

}

}

fn wait_for_io(&self) -> std::io::Result<Vec<Event>> {

self.reactor.borrow_mut().poll()

}

fn wake_futures_on_io(&self, events: Vec<Event>) {

let wakers = self.reactor.borrow_mut().get_wakers(events);

let _ = wakers

.into_iter()

.map(|waker| waker.wake())

.collect::<Vec<_>>();

}

}

It has two public API methods - block_on and spawn. These are the equivalent of the Tokio methods and do roughly the same thing. block_on is used for the top level future and blocks the main thread waiting for this future to complete, and spawn is used for nested futures.

You’ll notice that all my futures have an output of the unit type and have a static lifetime. The former is done to simplify the code since this runtime is only going to service a web server, which typically write their results back via the TCP stream.

I did the latter because it was the easiest way to set up everything without having to worry about lifetimes. If you’re interested in a way that futures can be built without any lifetimes at all, read this great post by Evan Schwartz.

And with that, we’re done with the main internal components of our system.

Custom Futures

Now, that we have internal components mainly set up, let’s switch focus over to writing some custom futures which can be run on the executor.

We’re going to be building a basic web server on top of this, so let’s buid a simple TCP listener & client.

TCP Listener

Here’s the code for the listener. Notice that it registers interest with the reactor upon recognizing that there are no clients attempting to connect right now. Also, notice the drop functionality where it unregisters itself from the reactor.

The listener.set_nonblocking(true) is important here because otherwise the connect function call will block on the async task, rendering the entire runtime pointless.

When the listener notices that there are no clients trying to connect, it registers interest with the reactor and unblocks the scheduler.

pub struct TcpListener {

listener: std::net::TcpListener,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

}

impl TcpListener {

pub fn bind(addr: &str, reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>) -> std::io::Result<TcpListener> {

let listener = std::net::TcpListener::bind(addr)?;

listener.set_nonblocking(true)?;

Ok(Self { listener, reactor })

}

pub fn accept(&self) -> std::io::Result<ListenerFuture> {

Ok(ListenerFuture {

listener: &self.listener,

reactor: Rc::clone(&self.reactor),

})

}

}

impl Drop for TcpListener {

fn drop(&mut self) {

self.reactor

.borrow_mut()

.remove(

self.listener.as_raw_fd(),

Event::all(self.listener.as_raw_fd() as _),

)

.unwrap();

}

}

pub struct ListenerFuture<'listener> {

listener: &'listener std::net::TcpListener,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

}

impl Future for ListenerFuture<'_> {

type Output = std::io::Result<(std::net::TcpStream, std::net::SocketAddr)>;

fn poll(

mut self: std::pin::Pin<&mut Self>,

cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>,

) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

debug!("Received a poll call on the ListenerFuture");

match self.listener.accept() {

Ok((stream, addr)) => std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok((stream, addr))),

Err(e) if e.kind() == std::io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock => {

debug!("Attempting to accept a connection on the listener WouldBlock, so registering with reactor and yielding control back to the executor");

let fd = self.listener.as_raw_fd();

self.as_mut().reactor.borrow_mut().register_interest(

fd,

super::reactor::InterestType::Read,

cx,

);

std::task::Poll::Pending

}

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("received an error in the ListenerFuture {}", e);

std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(e))

}

}

}

}

TCP Client

The TCP client is a little more involved but it’s useful to break this down into a set of smaller components as well. While handling a request:

- the client reads bytes from the stream

- reads a response file from the local fs using the threadpool

- writes a response back to the stream

Here’s the code

pub struct TcpClient {

client: TcpStream,

_addr: SocketAddr,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

file_io_pool: Rc<RefCell<FileIOPool>>,

}

impl TcpClient {

pub fn new(

client: TcpStream,

addr: SocketAddr,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

file_io_pool: Rc<RefCell<FileIOPool>>,

) -> Self {

client.set_nonblocking(true).unwrap();

Self {

client,

_addr: addr,

reactor,

file_io_pool,

}

}

pub async fn handle_request(&mut self) -> std::io::Result<()> {

debug!("handling client request");

self.read().await?;

let file_path = PathBuf::from("hello.html");

let bytes = self

.file_io_pool

.borrow()

.read_file(file_path, Rc::clone(&self.reactor))

.await

.expect("Error while reading the response file");

let mut response = Vec::new();

let headers = format!(

"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Length: {}\r\nConnection: close\r\n\r\n",

bytes.len()

);

response.extend_from_slice(headers.as_bytes());

response.extend_from_slice(&bytes);

self.write(response).await?;

self.client.shutdown(std::net::Shutdown::Write)?;

Ok(())

}

fn read(&self) -> AsyncTcpReader {

AsyncTcpReader {

client: &self.client,

reactor: Rc::clone(&self.reactor),

buffer: Vec::with_capacity(1024),

total_read: 0,

}

}

fn write(&self, buffer: Vec<u8>) -> AsyncTcpWriter {

AsyncTcpWriter {

client: &self.client,

reactor: Rc::clone(&self.reactor),

buffer,

bytes_written: 0,

}

}

}

impl Drop for TcpClient {

fn drop(&mut self) {

self.reactor

.borrow_mut()

.remove(

self.client.as_raw_fd(),

Event::all(self.client.as_raw_fd().try_into().unwrap()),

)

.unwrap();

}

}

pub struct AsyncTcpReader<'read_stream> {

client: &'read_stream TcpStream,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

buffer: Vec<u8>,

total_read: usize,

}

impl<'read_stream> Future for AsyncTcpReader<'read_stream> {

type Output = std::io::Result<usize>;

fn poll(

mut self: std::pin::Pin<&mut Self>,

cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>,

) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

loop {

let mut chunk = [0u8; 1024];

match self.client.read(&mut chunk) {

Ok(0) => {

// received EOF

self.buffer.clear();

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(self.total_read));

}

Ok(n) => {

self.buffer.extend_from_slice(&chunk);

self.total_read += n;

let headers = std::str::from_utf8(&chunk[..n]).unwrap();

if headers.ends_with("\r\n\r\n") {

self.buffer.clear();

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(self.total_read));

}

return std::task::Poll::Pending;

}

Err(e) if e.kind() == std::io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock => {

self.reactor.borrow_mut().register_interest(

self.client.as_raw_fd(),

InterestType::Read,

cx,

);

return std::task::Poll::Pending;

}

Err(e) => return std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(e)),

}

}

}

}

pub struct AsyncTcpWriter<'write_stream> {

client: &'write_stream TcpStream,

reactor: Rc<RefCell<Reactor>>,

buffer: Vec<u8>,

bytes_written: usize,

}

impl<'write_stream> Future for AsyncTcpWriter<'write_stream> {

type Output = std::io::Result<usize>;

fn poll(

mut self: std::pin::Pin<&mut Self>,

cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>,

) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

let this = self.as_mut().get_mut();

loop {

match this.client.write(&this.buffer[this.bytes_written..]) {

Ok(n) => {

this.bytes_written += n;

if this.bytes_written >= this.buffer.len() {

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(this.bytes_written));

}

}

Err(e) if e.kind() == std::io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock => {

this.reactor.borrow_mut().register_interest(

this.client.as_raw_fd(),

InterestType::Write,

cx,

);

return std::task::Poll::Pending;

}

Err(e) => {

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(e));

}

}

}

}

}

Notice that because we have a threadpool via which to read files, all of the 3 tasks above become asynchronous.

Wiring It All Up

Now, that we have all the different components, we need to wire everything up together.

Here’s the main function where we’ll build the top-level future and then pass it along to the executor. It’s quite ugly because of the excessive Rc syntax, but that’s just Rust I suppose.

use std::{cell::RefCell, rc::Rc};

use log::debug;

use timer_future::async_runtime::{

client::TcpClient, executor::Executor, file_io_pool::FileIOPool, listener::TcpListener,

reactor::Reactor, task_queue::TaskQueue,

};

fn main() {

env_logger::init();

let task_queue = Rc::new(RefCell::new(TaskQueue::new()));

let reactor = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Reactor::new().unwrap()));

let (shutdown_tx, shutdown_rx) = std::sync::mpsc::channel();

setup_ctrlc_handler(shutdown_tx);

let file_io_pool = Rc::new(RefCell::new(FileIOPool::new(5, shutdown_rx)));

let runtime = Rc::new(Executor::new(task_queue, Rc::clone(&reactor)).unwrap());

let runtime_clone = Rc::clone(&runtime);

runtime.block_on(async move {

let listener = TcpListener::bind("localhost:8000", Rc::clone(&reactor)).unwrap();

while let Ok((client, addr)) = listener.accept().unwrap().await {

debug!("Received a client connection from client {:?}", client);

let reactor_clone = Rc::clone(&reactor);

let file_io_pool_clone = Rc::clone(&file_io_pool);

runtime_clone.spawn(async move {

let mut tcp_client =

TcpClient::new(client, addr, reactor_clone, Rc::clone(&file_io_pool_clone));

tcp_client

.handle_request()

.await

.expect("Error occurred while handling the tcp request");

});

debug!("Handed off client connection to executor");

}

});

println!("Done executing the top level future");

}

fn setup_ctrlc_handler(shutdown_tx: std::sync::mpsc::Sender<()>) {

ctrlc::set_handler(move || {

shutdown_tx

.send(())

.expect("failed to send shutdown signal");

})

.unwrap();

}

There’s some additional functionality around shutting down the entire runtime by listening for a SIGINT, but the meat of the code is in the block_on function. The connect loop listens for connections, and upon receiving one immediately spawns a separate task for the client.

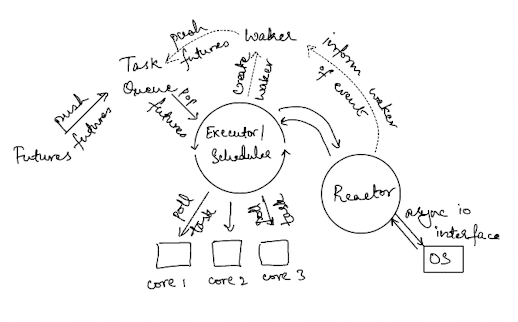

That was a lot of code, so let me leave you with another diagram illustrating what we’ve built. It’s very similar to the diagram I shared earlier with some more detail attached.

It looks a lot more complicated but it’s just showing more of the detail in the system, the core components remain the same. I’m showing multiple cores being utilized in the diagram, whereas we just utilized one core.

Conclusion

So, there we have it - a single-threaded async runtime which shows how to use async IO to wait on events and poll tasks via a scheduler in ~900 lines of Rust code. Building this prototype was a great way for me to intuit the core ideas behind an async runtime for myself.

Of course, there’s a lot we skipped over here for the sake of simplicity:

- most production schedulers are multi-threaded with tasks being multiplexed across these threads (for our example, we’d end up having to use

Arcinstead ofRc) - timers in an async runtime & cancellable tasks

- work stealing across threads, something Tokio famously does

- thread-per-core model with tasks pinned to specific threads

I hope this post gives you a better idea of what’s going on under the hood of an async runtime.